Advantages of Direct Composite Resin Veneers When Masking Tooth Discoloration Restorations

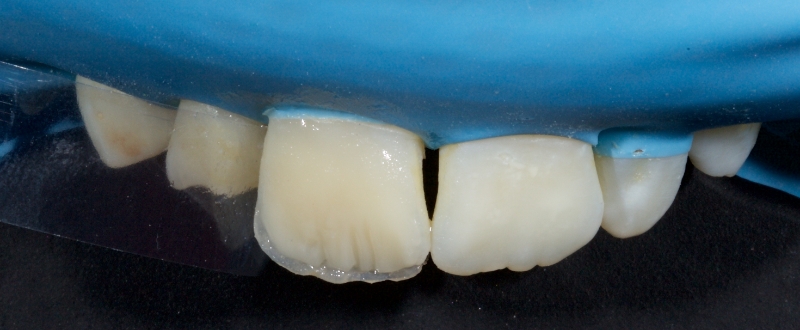

Not all discolored teeth are responsive to conservative approaches like nightguard vital bleaching (NGVB) or non-vital bleaching. Even if an excellent initial outcome is achieved, sometimes relapse occurs. Therefore, when bleaching fails, restoration consideration should be given to a masking procedure using indirect or direct composite resin veneers.

Using a direct composite resin veneer over an indirect approach for single anterior units has some advantages:

- The operator controls the restoration’s masking, layering, and morphology.

- The procedure can be completed in a single visit.

- The procedure is more cost-effective.

The exception is teeth that are structurally compromised, such as endodontically treated teeth with extensive Class III restorations.

Composite Resin Veneer Selection

Composite resin is supplied in many shades and three main opacities:

For example, Kulzer Venus Pearl clear (CL) or Tokuyama white enamel (WE) mimics enamel in areas where the underlying layering wants to be seen. Typically, this is placed as a final layer on the incisal third of the facial surface.

For example, DMG Ecosite Elements A2 or Dentsply TPH Spectra ST A1 are used where translucency and a degree of color (chromaticity) are required. They are usually used as a final layer on the gingival or mid-third of the tooth.

For example, Ivoclar A3 dentin or GC G-aenial AO2 are highly opaque (light-blocking) masses with color. They are used for dentin replacement or for masking discoloration.

- Highly Translucent Achromatic Enamel

- Medium Translucency Chromatic Enamel

- Opaque Chromatic Dentin

Due to its inherent translucency, the composite resin is limited in its opaquing ability, especially in thin sections. Specialized opaquers must be employed when masking discoloration to increase value and decrease chroma.

Opaquers are highly pigmented resins containing metal oxides responsible for opacification. These metal oxides are usually titanium or aluminum oxide and achieve increased opacity by increasing absorption and scattering light within the resin. Opaque chromatics may be sub-divided into:

- Paste Opaques: These opaque resins have the same viscosity as standard packable composite resin. I use them when a degree of control is required to shape the resin, for example, creating dentin mamelon effects.

- Flowable Opaquers: These are opaque resins with similar viscosity to flowable composite resin. An example would be Kulzer Venus Baseliner. I use these where masking of discoloration is required in a very thin section. The resin is typically applied in thin layers with a brush and light-cured between layers.

- Pink Opaquers: This is a flowable opaquer with a pink hue used when managing an extremely discolored substrate or masking metal.

Clinical Tips: Applying Flowable Opaquers

- Choose an opaquer that is similar to the desired dentin shade in terms of chromaticity (hue and chroma). The chromaticity can be modified by adding composite resin tints (often brown, amber, ochre, or white) before applying the opaquer.

- Apply an even, homogenous layer of the opaquer to avoid the appearance of spotting (theshine through of highly opaque or discolored areas in the final restoration).

The opaquer is usually applied with a No. 3 artist’s brush or Tokuyama No. 24 brush. Initially, the brush is loaded, which means it is dipped into a composite modeling resin (e.g., BISCO modeling resin). Loading the brush leads to a more even application of the opaquer. Excess modeling resin is removed by wiping the brush on gauze. The opaquer is then applied in multiple thin, even layers polymerizing each layer before the next application. The opaquer is applied from gingival to incisal, taking care to avoid pooling. Usually, 3-5 layers are required, according to a 2013 paper by J.S. An. - According to Felippe and Baratieri, care should be taken to allow a minimal thickness of 0.4 mm for the layering of the resin veneer after the opaquer application is completed.

Bleach Gone Bad: A Case Study

References

- Liebenberg, W. H. (1997). Intracoronal lightening of discolored pulpless teeth: A modified walking bleach technique. Quintessence International, 28(12).

- An, J. S., Son, H. H., Qadeer, S., Ju, S. W., & Ahn, J. S. (2013). The influence of a continuous increase in thickness of opaque-shade composite resin on masking ability and translucency. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 71(1), 120-129.

- Cherukara, G. P., Seymour, K. G., Zou, L., & Samarawickrama, D. Y. D. (2003). Geographic distribution of porcelain veneer preparation depth with various clinical techniques. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 89(6), 544-550.

- Felippe, L. A., & Baratieri, L. N. (2000). Direct resin composite veneers: masking the dark prepared enamel surface. Quintessence International, 31(8).

- Friedman, S., Rotstein, I., Libfeld, H., Stabholz, A., & Heling, I. (1988). Incidence of external root resorption and esthetic results in 58 bleached pulpless teeth. Dental Traumatology, 4(1), 23-26.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Jason Smithson

Date: August 18, 2022

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts