Accidental Ingestion of Dental Materials: Treatment and Prevention

The accidental ingestion or aspiration of dental instruments, dental prostheses or materials used during the course of treatment can occur in virtually any field of dentistry and during nearly any procedure. In fact, the literature contains multiple case reports in which significant complications have occurred after swallowing or aspiration of dental restorations outside of the dental office. Intraoperative accidents are not limited to small objects; items as large as air-water syringe tips have reportedly gone “down the hatch.”

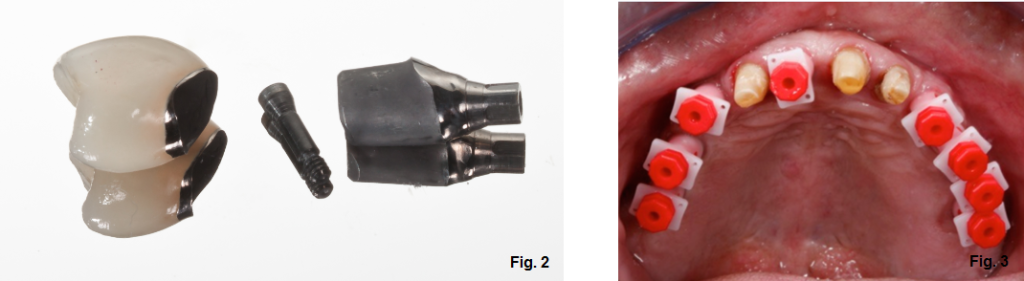

These possible complications can be especially troublesome during implant procedures, because of the small size and complexity of the components and the frequent inability to use a rubber dam. Some implant instruments such as drivers have small holes through which floss ligatures can be tied, but most implant components don’t have such attributes, so different management strategies must be employed.

Where did that go?

When an implant instrument, component or restoration disappears into the oropharynx, it’s impossible to know with certainty where it will end up. According to Abusamaan et al., as many as 80% of these objects are swallowed, while the remaining 20% are aspirated. It is thought that foreign-body aspiration is significantly less frequent due to the violent coughing that occurs and, fortunately, often leads to spontaneous ejection of the object.

What now?

Because it’s difficult or impossible to determine where the object has gone clinically, most authors suggest positioning the patient in the reverse Trendelenburg position and asking them to cough. A foreign body that has been aspirated constitutes a medical emergency and requires immediate treatment. Symptoms of laryngeal obstruction include choking, labored breathing, and stridor. If the object can’t be removed immediately with suction or forceps, the clinician should immediately activate the emergency medical system (EMS) and continue to attempt to maintain the patient’s airway, according to their level of training.

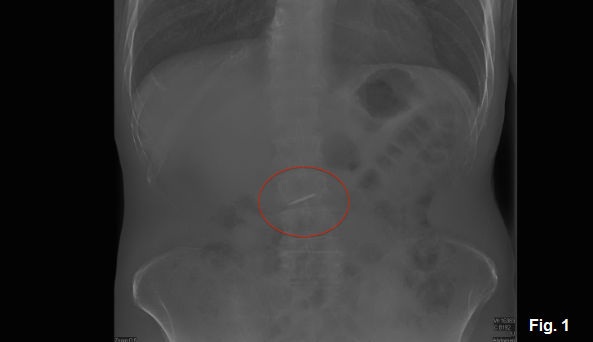

If the patient is asymptomatic, it’s important to remain calm, reassure them and inform them about the complication and the need for immediate medical examination. Generally, frontal and lateral chest and/or abdominal radiographs should be used to locate the object.

A pound of cure

Aspirated foreign bodies are increasingly treated with endoscopy as the means for retrieval, while more difficult retrievals may require different techniques. Ultimately, the treating medical personnel will make the decision regarding how and when to proceed.

The complication that is most feared when a foreign body is swallowed is perforation. Perforation is rare; Abusamaan et al. report rates of perforation of 1% or less, and it tends to occur more frequently when the swallowed object is sharp enough to pierce an organ. Chances for perforation increase as the sharp object advances, potentially resulting in life-threatening conditions. In addition, sharp, pointed, and elongated objects may become impacted or embedded in mucosal folds and fail to pass.

As a result, the decision to remove an ingested foreign body will be based on the size and shape of the object. If a more conservative “wait and see” approach is taken, careful monitoring in necessary. In the event that a swallowed object is not retrieved and has not passed after one week, or if the patient becomes symptomatic, Abusamaan et al. suggest additional imaging and referral for endoscopic removal. (Clinicians may refer to the Abusamaan article cited for a more complete explanation of that group’s proposed algorithm for the management of aspirated or ingested dental objects.)

It’s important to be aware that conventional radiography may be insufficient to locate items that are not sufficiently radiopaque. Radiolucent components or prostheses, such as those made from acrylic or composite resin, may require alternative imaging modalities. It’s crucial that clinicians characterize the object in terms of shape, size, and material when an accident occurs and pass that information on to the treating physician.

An ounce of prevention

With implant procedures, the main method to prevent aspirated or ingested objects is the routine placement of a throat pack. Additionally, instruments may have floss ligatures affixed, where appropriate, to aid in retrieval. Use of larger laboratory-type drivers may decrease the likelihood of the instrument being dropped. Some authors have advocated placing the abutment screws into the prosthesis before delivery and then placing some kind of gel in the screw channel in an attempt to avoid losing the abutment screw during insertion. Clinicians may elect to use a rubber dam where appropriate.

Careful monitoring of implant instruments, components, and prostheses will prevent “false alarms,” situations where an object is missing and no one is sure where it went — or, perhaps worse, no one notices the object is missing.

Zitzmann et al. have identified several factors that predispose patients to ingestion or aspiration of foreign bodies. Patients with cognitive deficiencies, a history of drug and/or alcohol abuse, excessive gagging, or who are overweight are at a higher risk of foreign body ingestion accidents. (Click here for six methods for dealing with gagging patients.)

Perhaps most notable is the relationship between foreign-body ingestion and the wearing of complete dentures. This phenomenon is ascribed to the reduced tactile sensitivity of the palatal mucosa and definitely comes to bear when working with implant-assisted and implant-supported overdentures and full-arch fixed prostheses, because these patients frequently have removable interim prostheses.

Foreign-body aspiration tends to occur more often in patients with impaired central nervous system function. CNS function may be affected by medications, so a careful review of the patient’s current medications is prudent.

Warning the patient ahead of time of the potential for a dropped object may help them to remain alert and allow them to “catch” the object and spit it out before any problem develops. Altering the way the patient is positioned, even temporarily, may aid in the retrieval of a dropped object.

Ultimately, practitioners are reminded to be careful, use strategies to prevent complications, and have a plan for “what-if” scenarios and a way to inform medical personnel of what type of material the object is made of, as well as its shape and dimensions.

Be prepared

Early diagnosis remains the key to successful treatment and minimally complicated management of aspirated or ingested objects. Failing to address objects that are lost intraoperatively can pose significant medico-legal risk and can have severe consequences for the patient. Having a plan in place can help reduce some of the stress and potential for miscommunication that occurs with any kind of medical emergency.

Teams should consider how they would respond to the immediate needs of a patient with a compromised airway, as well as how they would manage a patient when they suspect an object as been inhaled or swallowed. Questions like which hospital or physician the patient will be referred to, who will pay for treatment, and how the patient will be followed up are all better asked before this kind of complication occurs. Finally, teams should examine how they are trying to prevent foreign-body accidents in general, and specifically during implant treatment.

References

- M. Bergermann, P.J. Donald, D.F. aWengen: Screwdriver aspiration. A complication of dental implnt placement. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1992; 21: 339-341

- N.U. Zitzmann, Dr med dent,a S. Elsasser, Dr med,b R. Fried, Dr. med,c and C.P. Marinello, Dr med dent, MS,d: Foreign body ingestion and aspiration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;88:657-60

- Gianguido Cossellu1, Giampietro Farronato1, Antonio Carrassi1, and Francesca Angiero2: Accidental aspiration of foreign bodies in dental practice: clinical management and prevention. Gerodontology 2013; doi: 10.1111/ger.12068

- Effrosyni Tsitrou1, George Germanidis2, Christina Boutsiouki1, Elisabeth Koulaouzidou1, Eugenia Koliniotou-Koumpia1: Accidental ingestion of an air-water syringe tip during routine dental treatment: a case report. Journal of Oral Science, Vol. 56, No. 3, 235-238, 2014

- Swallowed and aspirated dental prostheses and instruments in clinical dental practice: A report of five cases and a proposed management algorithm. Mazen Abusamaan, William V. Giannobile, Preeti Jhawar and Naresh T. Gunaratnam. JADA 2014; 145(5):459-463 10.14219/jada.2013.55

SPEAR NAVIGATOR

Transform how your practice runs by engaging the team through

coaching and training

A guided path to excellence through structured coaching and self-guided resources that will align your team, streamline processes and drive growth. Transform your practice by implementing Spear’s proven playbooks for developing and retaining a high-performing dental team.

By: Darin Dichter

Date: October 29, 2015

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts