A Guide to Anterior Open Bites

Editor’s Note: This article combines nine original articles by Dr. Frank Spear.

Anterior open bites are often misunderstood in dentistry, from what causes them to when and how they should be treated. The purpose of this article is to hopefully provide a better understanding of how to address this problem.

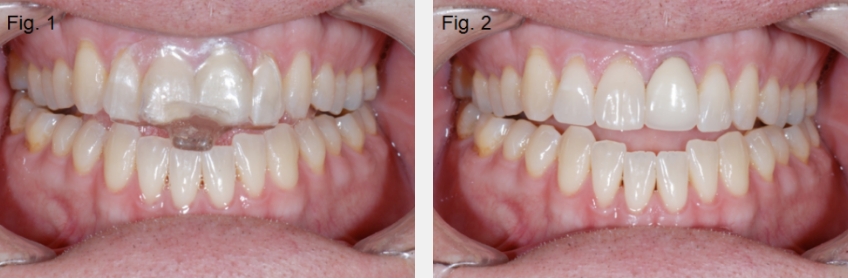

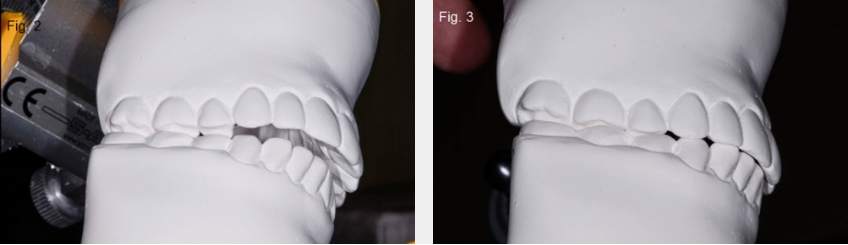

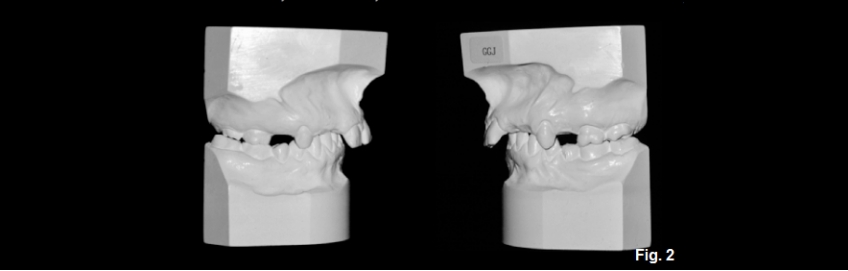

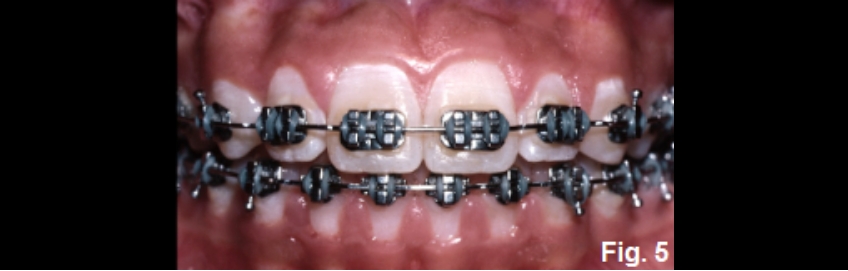

Anterior open bites can exist for several reasons, and it is helpful to identify the most common etiologies. Open bites can occur due to alterations of tooth position within an arch, or intra-arch (Figures 1 and 2). Examples include:

- Thumb sucking

- Tongue posture issues potentially related to airway disorders

- Excessive wear of segmental appliances (NTI or anterior bite plane)

- Abnormal eruption from ankylosis

Open bites can also occur due to alterations in the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla, or inter-arch. Examples include:

- Degenerative joint disease

- Class II or III skeletal relationship

- A steep mandibular plane angle, specifically in patients with a long face

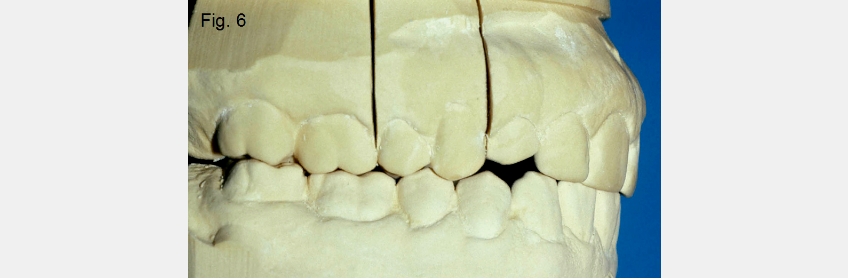

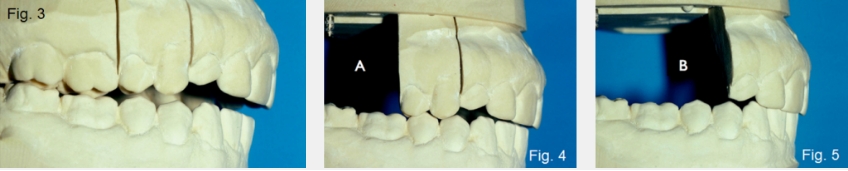

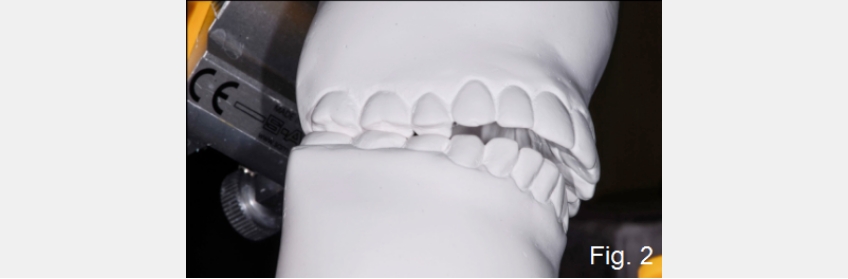

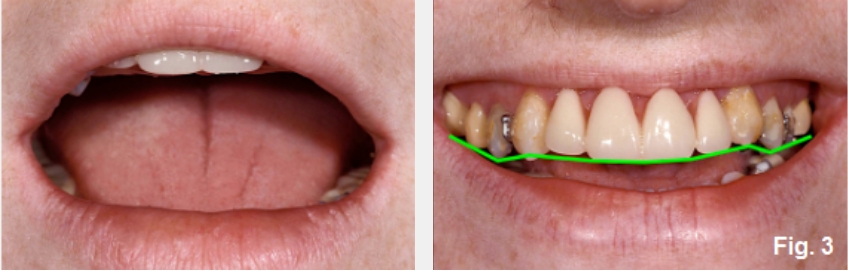

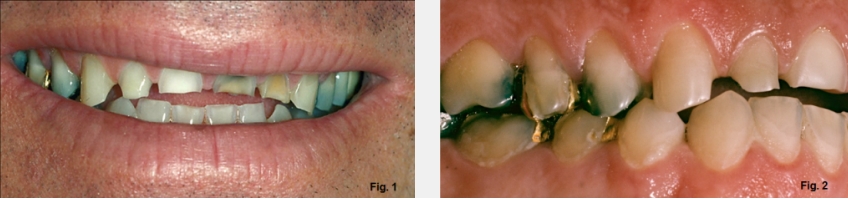

Finally, open bites can occur if there is tooth wear without secondary or compensatory eruption. A good example of this would be a patient who has erosive wear from sucking on lemons, but the compensatory eruption doesn’t keep up with the rate of wear (Figs. 3 and 4).

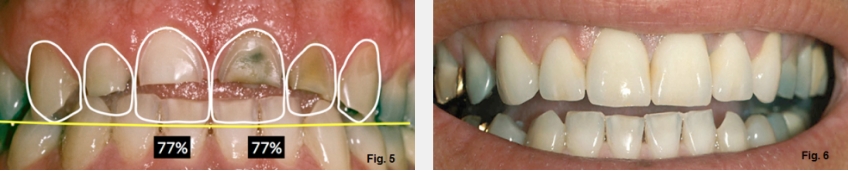

One of the simplest tools to aid in diagnosing the etiology of an anterior open bite is the use of hand-articulated study models. Suppose the hand-articulated models fit well regarding their occlusal relationship, but the patient cannot get their anterior teeth to touch. In that case, you don’t have a problem of tooth position within the arch — you have a problem related to the mandible’s position relative to the maxilla (Figs. 5 and 6).

In these patients, the open bite is typically very linear, meaning the molars have contact, but it becomes progressively larger as you move from the posterior to the anterior teeth (Fig. 7).

If the patient has issues with intra-arch tooth position, the hand-articulated models will display an open bite similar to what is seen in the mouth. Typically, the models will show an irregular pattern of eruption. In these patients, it is common to see a well-fitting posterior occlusion with just the anterior teeth — or even some of the anterior teeth — not in contact. Later, I’ll discuss the diagnosis for each of the typical causes of anterior open bites and the treatment options.

Open Bites Due to a Changing Relationship Between Maxilla and Mandible

Now I would like to talk about the possibilities if the problem is due to the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla. This usually means the hand-articulated models fit well, but the patient can’t get their anterior teeth together. This is a common outcome following degenerative joint disease, but it can also result in a significant shift between the patient’s seated condylar position and their habitual occlusion.

In these instances, it is not uncommon for patients to lose the muscle programming that allowed them to find their intercuspal position. This can occur after an alteration to their posterior occlusion, such as following the restoration or removal of a first or second molar, wearing an occlusal appliance, or initiating orthodontics.

Examining the history of these open bites can help diagnose the etiology. A key thing to look for is the timing of the onset. It is not uncommon for the onset of an open bite from degenerative joint disease to be progressive, and it can occur without symptoms other than the open bite.

In these patients, their anterior teeth would likely have touched at some point in time and will probably show evidence of some wear, such as a lack of mamelons. The open bite may be progressively getting worse, with the rate being dependent upon the rate of the progression of the degenerative process (Fig. 8).

In contrast, a patient with an open bite related to a change in the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible (from the lateral pterygoid muscle releasing and the mandible retruding) will typically have a history of some dental treatment. This could have been a restoration of a posterior tooth, extraction of a posterior tooth, appliance therapy, or the initiation of orthodontic therapy.

No matter the dental treatment, the open bite will likely have developed more quickly — and in some cases, this will happen immediately following treatment, not slowly and progressively. These possibilities make diagnosing the correct etiology critical before starting a path of treatment to correct the open bite. In future articles, I’ll discuss how to more definitively diagnose whether the joint condition is the etiology.

Open Bites Caused by Joint Issues

If the open bite has been slowly developing, I consider degenerative joint disease as a strong possibility. The lateral pterygoid may be responsible if the open bite occurred after some recent dental treatment that altered the posterior occlusion. Suppose you suspect that degenerative joint disease is a possibility. In that case, it is best to have the patient’s joints imaged to see the location and condition of the disk, as well as the form and condition of the bony structures of the condyle and fossa.

An MRI is the gold standard for imaging hard and soft tissue, but CBCT can reveal the condition of the hard tissues, and tomograms can also. The biggest concern is whether a degenerative process is occurring in the joints. Any treatment to correct the open bite may be a temporary correction, and the open bite will return as the joints degenerate. I’ve included some photos of a patient I treated in the 1980s — a case where I suspected the joints were the problem (Fig. 1A).

The challenge was the patient refused any imaging — back then, it would have been tomograms. She was convinced the problem had occurred because of a crown her dentist had recently placed. I placed her on a lower full-coverage appliance she wore 24 hours a day to see if her occlusion was continuing to change. After six months, the occlusion on the appliance remained stable (Fig. 2A).

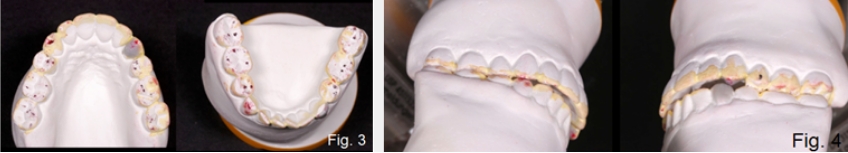

She informed me that she had told me it wasn’t her joints from the beginning, and since her bite on the appliance hadn’t changed, she was convinced she was right. She then asked what I would do to correct the open bite. I still didn’t have any joint images, and she refused them again. I mounted models and discovered that if I restored her molars with occlusal coverage restorations and equilibrated her premolars, her anterior teeth would touch ideally (Figs. 3A-5A).

The molars needed restorations anyway, so we proceeded to treatment without any joint images. The final result was perfect — the anterior teeth touching as predicted from the mounted models and diagnostic wax-up. However, her open bite returned with the same pattern six months later — contact on the second molars, then a linear opening increasing as it moved anteriorly. She now agreed to get the joint images I had requested in the beginning, and both joints had acute degenerative changes (Fig. 6A).

The lesson here is, if the patient’s open bite and history fit the degenerative model, image before deciding on a course of treatment.

Treatment Options for Anterior Open Bites in Patients With Stable Joints

Now I would like to discuss the treatment options available for patients who have anterior open bites due to the relationship of their maxilla to mandible, but have stable joints — unlike the patient I just described. Several options may be available for these patients to close the anterior open bite.

Before developing any plan to correct the occlusion, the starting point is to determine the correct anterior tooth position relative to the patient’s face. You can use tooth exposure with the lip at rest and images of a full smile to choose the desired anterior tooth position. In some patients, correcting the anterior tooth position may correct the open bite without any other occlusal changes.

For example, the patient I will use has an acceptable maxillary and mandibular anterior tooth position esthetically, but has no anterior tooth contact unless she protrudes her mandible into an end-to-end occlusal relationship. She will require occlusal alteration to close the open bite (Fig. 1B).

Her open bite is due to condylar fractures secondary to being kicked in the face by a horse at age 18. Effectively, the condylar fractures had the same impact on reducing joint height as the degenerative joint disease in the patient I showed previously. Her joints are stable and asymptomatic now (Figs. 2B and 3B).

One may ask: Why not leave the open bite since it has been there for over 15 years? To answer that, it is helpful to understand the risks associated with leaving a patient without anterior contact. There are two primary risks: secondary eruption of the anterior teeth to close the open bite. We notice in this patient that there appears to have been no secondary eruption. This is visible first because the open bite is still present — had the teeth erupted, the open bite most likely would not exist. And secondly, because the anterior teeth are in an acceptable position, had the teeth erupted, they would have appeared long or stepped down relative to her posterior teeth.

The second primary risk of leaving the anterior open bite is functional. We typically design our occlusions to have the anterior teeth contact and posterior teeth separate, commonly known as posterior disclusion, when the mandible moves. Without anterior contact, the posterior teeth are now in contact during excursions, potentially producing wear, fractures, or mobility of the posterior teeth. In addition, the lack of posterior disclusion may result in muscle hyperactivity in some patients, producing exacerbated dental symptoms or pain.

This patient doesn’t present with overeruption of the anterior teeth or pain, but she does have significant posterior tooth wear, particularly on the right side (Fig. 4B).

She hasn’t had any secondary eruptions because she wears a full-coverage bite appliance every night when she goes to sleep. It acts as a retainer, preventing secondary eruption. In addition, she has significant headaches if she forgets to wear the appliance. Her goals are simple: improve the appearance of her anterior teeth and correct her occlusion so she can eliminate the nightly appliance wear. Now we will look at her options for correction.

4 Ways to Close an Open Bite

This patient is now in her mid-thirties and asymptomatic. Still, she must wear a full-coverage bite appliance every night or risk secondary eruption of her anterior teeth from the open bite. In addition, she has significant posterior wear from the lack of any anterior guidance, and gets headaches regularly if the appliance isn’t worn (Fig. 1C).

In her case, the intra-arch alignment of the teeth is acceptable, and the position of her anterior teeth in her face is reasonable. Her anterior open bite is related to the relationship of the maxilla to the mandible.

In cases like these, typically four treatment options exist if the desire is to close the anterior open bite.

The first option I generally consider for an anterior open bite is occlusal equilibration — altering the posterior occlusion by reshaping the teeth, effectively closing the vertical dimension and bringing the anterior teeth into contact. The risk of equilibration is that it may require excessive tooth reduction, exposing dentin in the process, and it may be inadequate to achieve the necessary closure to gain anterior contact. For these reasons, a trial equilibration is typically performed on mounted models to see if the desired occlusion can be obtained with just equilibration, and to evaluate the amount of alterations necessary to the posterior teeth (Figs. 2C to 4C).

If equilibration cannot achieve the desired result, a second option to close an anterior open bite would be to add some restorations to the plan. This may be helpful to allow more posterior reduction than equilibration alone, but restorations can also be placed on maxillary or mandibular anterior teeth to gain contact. With the outstanding wear characteristics of modern composites, these restorations are often bonded additions requiring no tooth preparation.

A third and obvious option to close the anterior open bite is orthodontics — but this is not always as simple as it seems. For an orthodontist to gain anterior contact, they have to reduce the anterior open bite without over-erupting the anterior teeth relative to facial esthetics. In this patient, this leaves reducing overjet or closing the posterior vertical dimension as the alternatives.

Thankfully, this patient has crowded lower anterior teeth, and aligning them with orthodontics will lengthen the lower arch, reduce overjet, and increase the likelihood of closing the anterior open bite with equilibration. If the anterior open bite still can’t be managed after orthodontic alignment of the mandibular anterior teeth, intrusion of posterior teeth using mini-screws for orthodontic anchorage could close the vertical dimension and gain anterior contact (Fig. 5C).

Of course, the orthodontics could only be successful if the patient’s mandible is not excessively retrognathic, otherwise known as Class II. If it is, then the final option to correct the anterior open bite would be to consider mandibular advancement. All of this is determined by evaluating the patient’s tooth position and facial esthetics from photographs, and performing the trial equilibration on mounted models. If it is not successful, an ortho set-up can be done and evaluated. In addition, a diagnostic wax up simulating any proposed restorations can be included on the models as well.

Ultimately, this patient’s treatment did not require orthognathic surgery. However, it did require orthodontic correction of the mandibular anterior teeth, occlusal equilibration, four full-coverage restorations for esthetic reasons on the incisors, and bonded composite on the lingual of the maxillary left canine (Fig. 6C).

Treating an Anterior Open Bite Due to Excess Overjet and Missing Teeth

We will now look at a patient with normal joints, but an excess overjet resulting in an anterior open bite; she is also congenitally missing multiple maxillary teeth. As is typical in patients with excess overjet, she has an extremely deep overbite, the mandibular anterior teeth impinging on her palate (Figs. 1D and 2D).

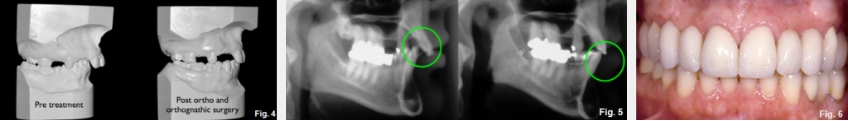

In these cases, the overjet will need to be reduced to allow for the development of a normal anterior relationship. Reducing overjet is typically done by either retracting the maxillary anterior teeth or advancing the mandibular anterior teeth; either can be done by orthodontics alone or combined with orthognathic surgery.

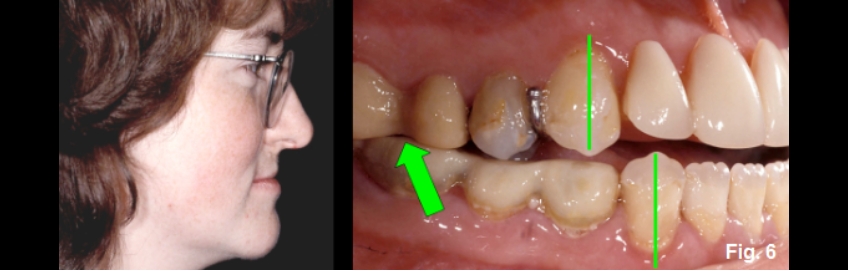

The Ideal Plan for Anterior Open Bite Patients With Excess Overjet

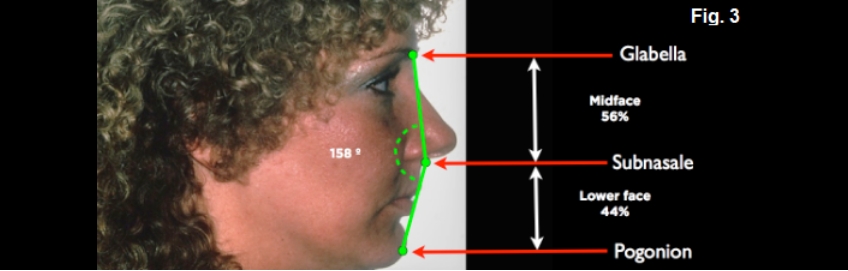

A very useful tool for deciding on what the ideal plan should be is a facial profile photograph of the patient with their lips together and face at rest. On the photograph, identify glabella — the smooth area between the eyebrows; subnasale- the junction of the base of the nose and upper lip; and pogonion — the most prominent point of the chin. Draw a line from glabella to subnasale, and subnasale to pogonion. Measure the angle formed at the junction of the lines — a normal range would be 165 to 175 degrees. The patient illustrated measures 158 degrees, indicating her chin is retrognathic, skeletal class II.

In addition, the vertical distance between the same points should be measured. If you use the distance from glabella to pogonion as 100%, the distance from glabella to subnasale (midface) should be 45% to 50%; from subnasale to pogonion (lower face), 50% to 55%. In the patient shown, her midface is 56% and her lower face is 44%. She is a patient who would benefit functionally and esthetically from a mandibular advancement. The advancement would correct her retrognathic mandible and the vertical dimension of her face (Fig. 3D).

The actual treatment consisted of orthodontics to idealize maxillary tooth position, followed by mandibular advancement, and then the final orthodontic correction of the occlusion (Figs. 4D and 5D). Ultimately, she had prosthetic treatment to replace the missing maxillary teeth (Fig. 6D).

FGTP and Anterior Open Bites

Now, I want to focus on the specific treatment planning sequence necessary to correct the esthetic and functional components of anterior open bites. At Spear, we call this process Facially Generated Treatment Planning (FGTP), a term I first used in a lecture in 1986. The concept is simple. Even though there are issues that are more serious to maintaining teeth than esthetics-such as periodontal health, endodontic status, caries, occlusion, etc. — we must treatment plan the position of the maxillary teeth relative to the face first (esthetics), before we develop the occlusion (function), or decide how to treat the other areas of concern (structure and biology) — what we refer to as EFSB for short. It is important to note that when we talk about FGTP, we are talking about the sequence of treatment planning, not the sequence in which the patient will be treated.

The patient in this photo is an ideal example of why the FGTP process is necessary. She is 30 years old, has an anterior open bite, and desires an esthetic correction and anterior tooth contact (Fig. 1E).

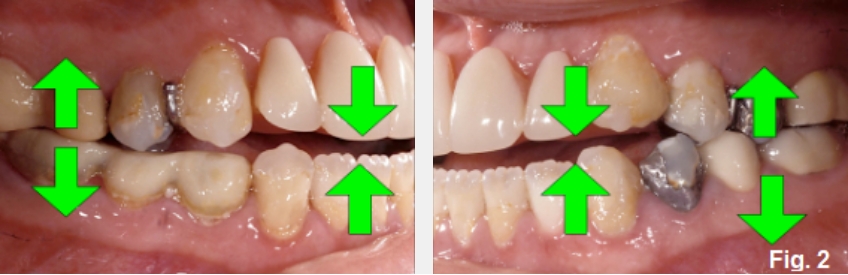

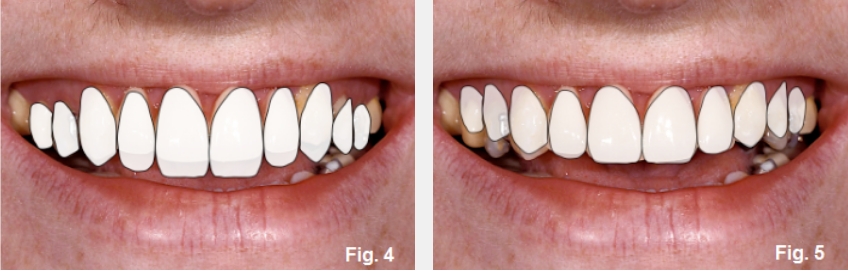

The second picture (Fig. 2E) identifies the options for closing the anterior open bite: lengthen the maxillary anterior teeth, lengthen the mandibular anterior teeth, shorten or intrude the maxillary posterior teeth, shorten or intrude the mandibular posterior teeth. The real question is, how will you know what to do? Mounted models won’t help you any more than this photograph does; you have to evaluate the position of the teeth relative to her face.

From a purely mechanical point of view, lengthening the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth would appear to solve the occlusal problem, but a photo of her lip at rest and full smile tells a different story (Fig. 3E).

Her central display at rest and in a full smile is pleasing, but her smile line is reversed. Again, lengthening the anterior teeth would seem to solve the problem, but she has excessive posterior tooth and gingival display from posterior over-eruption.

The fourth photo (Fig. 4E) simulates what her smile would look like if the anterior teeth were lengthened to match the posteriors, correcting the smile line and excessive tooth display. She would now show 7.0 mm of central at rest. The fifth photo (Fig. 5E) simulates what needs to happen: leave the anterior tooth position alone, correct the posterior tooth position to correct the smile line. This will eliminate the excessive posterior gingival display and close the anterior open bite. Typically, there are four options for correcting over-erupted posterior teeth: orthodontic intrusion using implant anchorage, crown lengthening and restoration, orthognathic surgery, and extraction and replacement with implants. In her case, the amount of change is too significant to consider crown lengthening. And at age 30, extractions seem to be a poor choice.

How do you decide between intrusion and orthognathic? Intrusion would correct the maxillary posterior tooth position, but in her case, she is dentally and facially Class III (Fig. 6E).

Orthognathic surgery to impact the posterior maxilla and advance the maxilla is ideal; the amount of movement is determined esthetically. The seventh photo (Fig. 7E) shows the before and after views of the left and right sides following orthognathic surgery — maxillary impaction and advancement — and restoration. However, the posterior intrusion was the significant treatment event for correcting the anterior open bite. That movement was mediated by the esthetic needs of correctly positioning the maxillary teeth in her face.

The final photo (Fig. 8E) shows the before-and-after facial images. It graphically shows the change in posterior tooth and gingival position and the improved smile line.

Anterior Open Bite From Intra-Arch Issues

Most cases I have shown were challenging to treat; they had combinations of intra-arch and inter-arch issues. I’ll now focus on a patient with an open bite from only intra-arch issues, specifically the tooth position in the maxillary arch due to a habit pattern. The good news about this patient is that she is young, has no tooth wear, and has a reasonably well-aligned mandibular arch. In addition, she has a Class I molar relationship and no inter-arch problems (Fig. 1F).

What Caused This Open Bite?

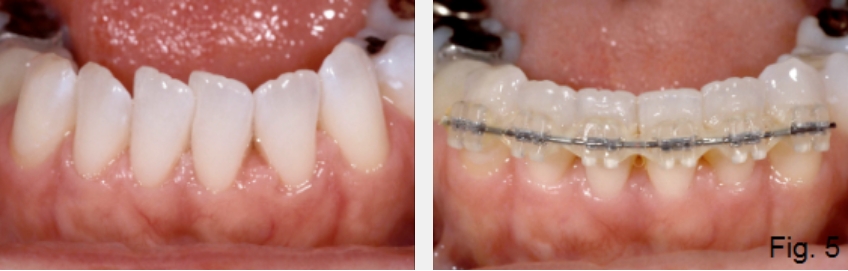

The challenge in these patients is that the open bite is due to under-eruption of some of the maxillary anterior teeth. The under-eruption could be caused by a habit, such as thumb-sucking, tongue posture, or something placed between the teeth, such as a pencil. The problem with the under-eruption is that it means the gingival margins are also apically positioned on the under-erupted teeth (Fig. 2F).

Because of this, non-orthodontic treatment plans — specifically, restorations to lengthen the under-erupted teeth to close the open bite — will always end up esthetically challenged with the under-erupted teeth. Specifically, her right lateral and central areas looked too long after restoration (Fig. 3F).

If crown lengthening were done on the left to make the gingiva match the right, all the incisors would look excessively long. In addition, the left central and lateral areas would need restorations to cover the exposed root surfaces following surgery. The obvious solution to these types of patients is orthodontics to correct the tooth position by extruding the under-erupted teeth into a normal alignment (Fig. 4F).

This brings the gingiva into the correct position and, in her case, eliminates the need for any restorations. Of course, the habit that caused the under-eruption must be addressed, or a recurrence of the open bite may occur. This is especially true in patients with tongue posture issues. Commonly, orthodontics may also have minor corrections of the opposing tooth position since habits may also alter it (Fig. 5F).

Ultimately, in a patient like this one, orthodontics and behavior modification surrounding the habit are by far the best treatment options, avoiding surgery or restorations (Fig. 6F).

Open Bite Caused by Lemon Sucking

The easiest open bite to correct is caused by tooth wear from erosion, not attrition or grinding, and where the anterior tooth position didn’t change with the tooth wear. These are also very uncommon patients, as eruptions commonly occur following wear and maintenance of the teeth in occlusal contact.

The patient in this open bite example is a male in his fifties who has a 25-year history of sucking lemons (Fig. 1G). A lateral view shows the posterior teeth from the first premolar back are all in contact, although they do show some evidence of facial erosion (Fig. 2G).

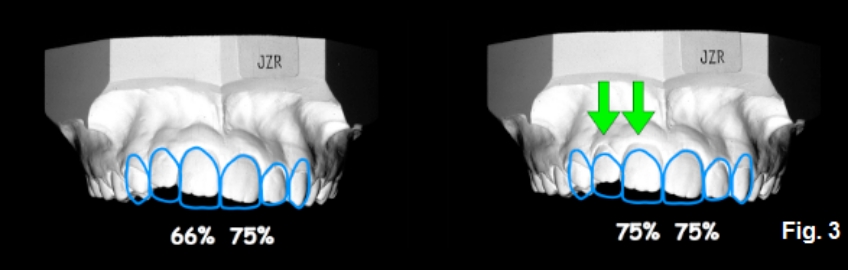

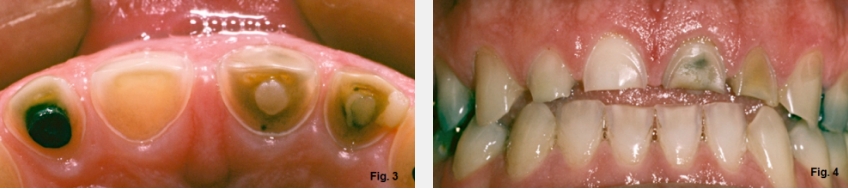

He bit through the lemon with his incisors and sucked the juice out around them, devitalizing three of the four incisors (Fig. 3G). Simply looking at this image doesn’t make it clear whether his anterior teeth have extruded with tooth wear or not (Fig. 4G).

It will be necessary to identify the correct incisal edge position of his teeth, then evaluate how the gingival levels relate to that position using the width-to-length ratio to assess whether the gingival margins are correct. This will tell you whether the teeth have erupted with wear or not. In this case, the drawings illustrate this open bite patient’s correct incisal edge position, basically level with his posterior occlusal plane. Measuring from the correct incisal edge to the existing gingival margins gives a ratio of 77%, a prevalent ratio for a pleasing central incisor. It appears he has no secondary eruption with the tooth wear, and will need the teeth restored without any gingival level alterations (Fig. 5G).

The good news is that there was room to place the restorations because he had an open bite. The even better news is that if he keeps sucking on lemons, the acid will have no impact on the porcelain restorations. Of course, it would be better for all his other teeth if he quit the habit. Due to finances, he only did the maxillary six anterior teeth. It would have been ideal if he could have returned to the first molars (Fig. 6G).

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Frank Spear

Date: December 3, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts