5 Elements of the ‘Less is More’ Approach in Interdisciplinary Treatment

By Ricardo Mitrani on September 17, 2019 | 2 commentsGerman American architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who is considered a pioneer of modernist architecture, adopted the term "less is more" to describe the esthetic principle of his work.

The concept revolved around deliberately including only the essential components of a building to create an element of extreme simplicity.

Conversely, over the years, dentist and dentistry alike have earned a reputation for consistently utilizing both invasive and aggressive techniques, which presents the notion of overtreating patients.

In today’s dental landscape, patients are becoming increasingly aware and sensitive to the implications of getting extensive dental work and are more interested in conservative approaches to tackle their dental conditions.

While there is a pretty slim line that divides overtreatment and negligence, I would like to present a comprehensive “less is more” concept, just like with architecture or design.

This concept revolves around five fundamental pillars:

- Maintain the most tooth structure

- Minimize the number of teeth involved

- Utilize the least invasive techniques

- Delay treatment

- Phase treatment

Maintain the most tooth structure

The full coverage restoration or crown has historically been one of the most popular dental solutions to restore extensive decay, protect the tooth post-endodontic treatment or as abutment teeth for conventional, fixed partial dentures.

Conversely, an essential feature for these types of restorations is the preparation’s geometry, since it needs to provide adequate forms of resistance and retention to prevent the restoration from dislodging.

However, with the advent of adhesive dentistry, the name of the game in retention is no longer related to preparation geometry (which, according to restorative textbooks, we relied on at least a 3.5-mm preparation height and relatively parallel walls with a 6-degree taper) but now we rely on the quality of the substrate and extension of the bonded surfaces.

A bonded overlay restoration can be perfectly suitable (Figure 1) and predictably inserted to restore an endodontically treated tooth, or a severely destroyed occlusal surface, without the need to extend the preparation axially to the gingival margin.

By preserving all that sound tooth structure and keeping our adhesive restorative margins as high and dry as possible, we are consistently contributing to prolonging the tooth’s longevity, since eventually it is reasonable to consider that most restorations will require replacement.

The more soundly we preserve tooth structure the more we delay the extractions and the need for implant placement. While implants are phenomenal solutions when teeth are lost, (as I explained in my article “The Biggest Dental Lie”) implant supported restorations should not be considered a “happily ever after” permanent solution, since they may also fail down the road.

In fact, our aim should be that there is no better implant than the one we avoid placing.

Minimize the number of teeth involved

In another recent article, “Patient Communication in the Age of Information,” I discuss how immediate gratification is one of the traits of the age. Patients are looking for fast dental makeovers that often require removing tooth structure, which potentially could be managed by orthodontically aligning teeth to improve their position without the need for restorative materials.

When patients are unsatisfied with the esthetic appearance of their smile and are seeking restorative work, it makes perfect sense to minimize the number of teeth involved. By using more conservative approaches – such as bleaching, reshaping or small composite restorations – we often do not need to involve all the anterior teeth.

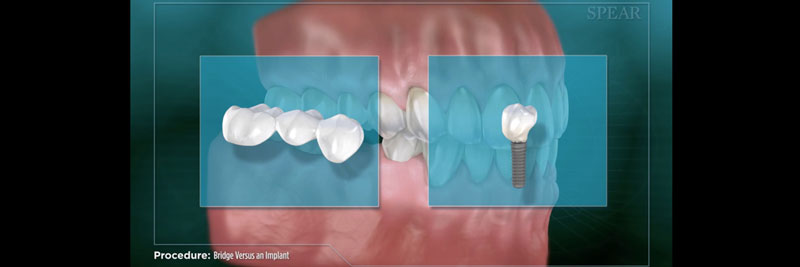

With the advent of osseointegrated implants, dentists have become increasingly cautious not to remove sound tooth structure on virgin teeth in order to provide fixed partial dentures. Our ability to replace missing teeth with implants allows us to preserve the integrity of these teeth, which unquestionably represents a more favorable prognosis (Figure 2).

Utilize the least invasive techniques

Just as we favor being minimally invasive when dealing with tooth reduction and number of teeth involved, technology has provided the dental team with modern armamentaria that allow us to perform procedures with the most conservative approach.

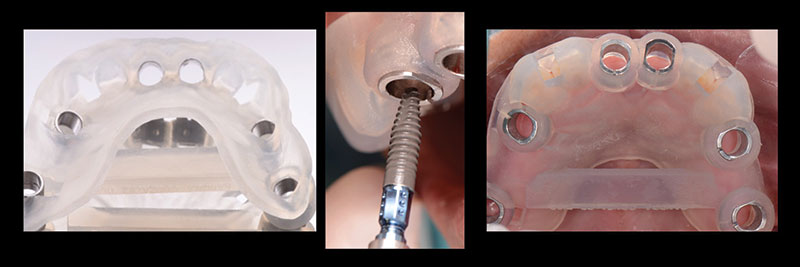

Examples include guided implant placement surgery that allows us to do minimal flaps when possible (Figure 3), development of instruments that allow us to perform mucogingival microsurgery, utilizing laser units in order to perform gingivectomies and frenectomies, and those that help us remove old ceramic veneers without running the risk of overpreparing sound tooth structure underneath the previous restorations (Figure 4).

Performing microscopic dentistry provides an incredible avenue to allow us to be as minimally invasive as possible.

Delaying dental treatment

With life expectancy on the rise, dentists need to develop long-term strategies in order to keep teeth healthier for the long-term. The best way we can substantially contribute to this endeavor is by delaying elective therapy and by diligently working toward creating a culture of prevention within the patient population.

As far as the ideal time for implant placement for congenitally missing teeth, particularly in the esthetic zone, there have been numerous recent scientific publications addressing a condition called continual craniofacial growth.

This condition may potentially affect esthetic results for patients with single-tooth implant restorations in the esthetic zone, since gingival margin and incisal edge discrepancies are feasible later. While this may not be an issue for patients that display a low lip line, we may want to be vigilant and caution our patients, particularly with female patients with long face syndrome (LFS).

By delaying implant placement in younger individuals, dentists need to develop strategies to keep teeth healthier for the long-term. Single retainer bonded bridges have proven to be an excellent solution for these patients.

Phasing treatment

For many patients, the most common deterrent to undergoing dental treatment is either lack of time or lack of financial means — especially if it’s a large treatment, even when patients fully understand they may require a full arch, or even a full-mouth reconstruction.

For these patients, and as the last pillar of our “less is more” philosophy, phasing therapy becomes a phenomenal strategy.

The idea is to break up treatment in either sextants or quadrants, or sometimes even by a few teeth at a time. This allows the patient to undergo extensive treatment in a more controlled fashion, minimizing long appointments (Figure 5).

If we think about it, all five of these pillars are quite linear and contribute significantly to a consistent narrative where the team is aligned to provide the best dental care available.

To paraphrase Dr. Robert Barkley: “The best dentist makes the patient worse at the slowest rate possible.”

Ricardo Mitrani, D.D.S., M.S.D., is a member of Spear Resident Faculty.

Comments

September 22nd, 2019

September 23rd, 2019