Caries Detection, Part I: What Do You See?

The science and practice of dentistry has evolved mightily over the past 20-plus years to astounding levels of understanding and insight. Innovation and technology has exploded and aren’t going away … and shouldn’t.

Patient evaluation has become more medically based. The need to discern and correlate a patient’s medical and dental conditions is paramount to their overall health, but the information we need to sift through is staggering and can overwhelm even the most seasoned of clinicians. It has the power to stall treatment. If one can’t compartmentalize the fact-finding, an approach to tie them together may become daunting.

Spear created a curriculum of learning to help any dentist with a methodical approach in patient education as well as their diagnosis and treatment. One workshop in particular can have an immediate impact on your practice: Treatment Planning With Confidence gives you the parameters to set up and think about all of the aspects of your patient’s health looking at the airway, esthetics, function, structure, and biology (AEFSB) of the patient. It is not to suggest we’re looking at every case as if esthetics is the most important; it’s only a starting point. We all know that the foundation of great outcomes in oral health is with sound hygiene, a patient’s biology.

It would be wonderful if all dental treatments were rendered under comprehensive treatment planning, but they’re not — most dentistry is still tooth-to-tooth. And this is fine, especially for the purpose of this article: caries detection. At the end of every day, we’re all tooth-to-tooth dentists because each tooth still requires its own level of attention when determining bacterial infiltration or bacterial effects on the architecture that houses said tooth.

Let’s turn the AEFSB model upside-down for a moment and focus on one small aspect of biology: the never-ending problem of interproximal caries. The bane of a tooth’s existence! They seem to occur in just about any dentition:

- People who brush poorly likely do not floss.

- People who brush well likely do not floss enough.

- Some people brush well and floss regularly, but not well enough.

- Other people brush and floss as well as can be expected, but are still subject to caries.

Even that last group still must deal with the other variables of tooth decay.

- Tooth hardness: genetics and fluoride exposure

- Diet: sugar and acid levels

- Salivary flow: alkaline or acidic; serous or mucus-like, abundant or dry

According to the Center for Disease Control,

- Children ages 2–17 with a dental visit in the past year: 83% (2013)

- Adults ages 18–64 with a dental visit in the past year: 61.7% (2013)

- Adults ages 65+ with a dental visit in the past year: 60.6% (2012)

- Children ages 5–19 with untreated dental caries: 17.5% (2011–2012)

- Adults ages 20–44 with untreated dental caries: 27.4% (2011–2012)

What may these statistics suggest when put together?

- The untreated dental caries is a result of those who haven’t had a dental visit in the past year. (What percentage of them haven’t had a visit in two or three years, or longer?)

- The untreated dental caries is a result of patients not having legitimate access to care.

- The untreated dental caries is the result of being informed of the caries and leaving its untreated due to:

- Fear

- Finances

- Lack of patient education

- The untreated dental caries is a result of misdiagnosis — or, better stated, of underdiagnosis.

Dental caries is still among the most chronic diseases prevalent among both children and adults, per a National Institute of Health study from 1999–2004. As dentists, we still don’t have a uniform agreement of which caries requires intervention (meaning treatment, predominantly for interproximal caries). The Class II lesion seems to be still up for discussion relative to intervention.

There are those who treat:

- At the first radiographic sign of the lesion, before it gets to the dentoenamel junction (DEJ)

- Once the lesion penetrates the DEJ on a radiographic image

- Only if a lesion is seen on a black-and-white image; if something appears identifiable on a PA image and not a black-and-white image, it often is observed until the next set of images

- At the first radiographic sign, not with a Class II restoration, but with a fluoride dentrifice

Patients go to their dentist and the one thing they expect is an evaluation of their oral health relative to bacteria: gum disease and tooth decay. All of the other aspects of dentistry — esthetics, function, TMD, oral cancer screening, sleep disorder screening, diet, etc. — take a back seat to bacteria. They deserve more of a consensus on the type of lesion that can become troublesome quickly.

The problem is in the eye test: All radiographic images are not created equal. It’s very common to recognize a Class II lesion, open up the tooth and find more area of decay than you envisioned. Waiting to see if you can arrest these caries may be all for naught, because it’s likely more advanced than meets the eye. I’d like to share with you examples of patients with lesions that were being “waited on,” “watched” or “observed.” All of them came into the office as new patients within the past few years. Without you having to toil and make a decision on what to treat, relax and look at these radiographs and their respective photographs in an exercise of the reality of Class II lesions.

(Spear members can click this link for a course on obtaining ideal images using oral radiography.)

Note: All of the photos within show the teeth during some portion of tooth preparation. The final preparations are not the purpose of this article!

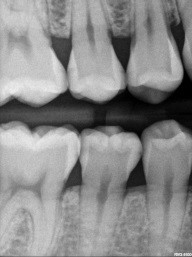

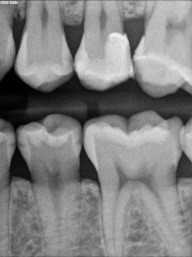

Patient 1: Tooth #12

This patient, who presented in 2015, brought her 2013 black-and-white image with her (the first images above). The second set of black and white images are from 2015. Notice the change in the interproximal caries. Even with a significant change (hypothetical) in a patient’s habit and fluoride delivery, how do these types of caries arrest predictably?

Again, the same patient, a photo of #29. Observe the black-and-white image again, then come back. Notice the color change at the distal ridge and the fissure (not a crack yet, as it was smooth on examination). The tooth has not yet been treated.

Patient 2: Tooth #28

A similar situation with a different patient, this time with caries to the DEJ. Caries were verified under the mesial of #29 as well and were more severe.

Patient 3: Tooth #12

This is a tough one for clinicians to believe, but the distal of #12 does, in fact, have caries! It appears less obvious and short of the DEJ. The photo mid-prep shows otherwise. Premolars, especially, are frail to begin with. Keeping any and all restorations conservative is the name of the game.

Patient 4: Teeth #12 and #13

On the black-and-white image, the patient has caries on #12, #13, #18, #19 and #20. We will focus on #12 and #13, especially the mesial of #13. The black-and-white image is less suggestive there than on #12. The photo tells a very different story. #13 is more advanced.

Patient 5: Tooth #18

This patient was referred from a periodontist who was going to extract #19 with socket preservation. The black and white image is deceiving, as they can be sometimes. Here, the mesial does not show a definitive lesion. It is here that the clinical examination is key. Do you examine and chase cracks? If a marginal ridge has a crack that is palpable to your explorer and is discolored, it is leaking. The photo image shows this well. The image that follows shows quite a different story than the black-and-white image. Notice the crack mid-prep is still quite prevalent.

I hope this article has made you at least a little more curious to what lies beneath those marginal ridges we examine each and every day. In Part II of this series, we’ll examine the advancements in technology and dentifrices that exist on the market, enabling us a better chance to diagnose, restore, or prevent further tooth destruction.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Dave St. Ledger

Date: May 21, 2018

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts