Planning the Class IV: Workhorse of Cosmetic Dentistry, Part 3

In part two of this series, we discussed strategies for optimally preparing the tooth substrate before bonding the Class IV. This article will discuss a protocol for layering direct composite to achieve esthetic success and functional durability. This protocol is standard for most resin systems on the market today.

To illustrate this protocol, we will explore the case of a 55-year-old female patient — a dentist — with esthetic and functional concerns as well as moderate to advanced tooth surface loss (TSL).

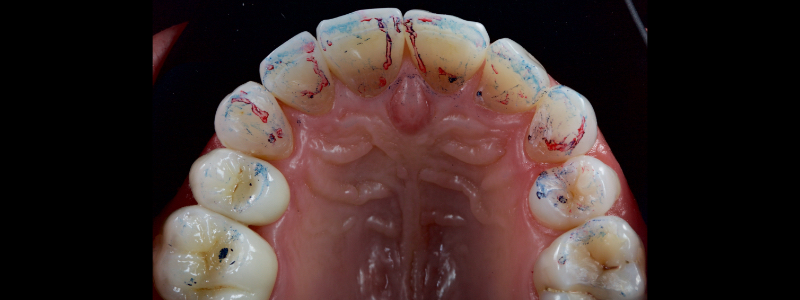

The anterior teeth had lost around 25% of the coronal structure, and dentin was exposed (Figs. 1–3). The patient requested a minimally invasive solution.

After deprogramming with a splint and occlusal equilibration, the anterior teeth were restored with direct composite resin using a minimal prep approach (Figs. 4 and 5). The occlusal scheme was idealized (Fig. 6).

What Makes a Resin System?

Although the nomenclature differs, most composite resin systems are used similarly based on relative translucency.

Translucency is defined as the ability of a substance to allow light to pass through it. High translucency is known as transparency — when light passes through a substance easily. Low translucency is called opacity and occurs when a substance blocks light transmission.

A natural tooth is made up of three main components:

- The dentin: This is an opaque substrate.

- The enamel-dentin junction (EDJ): This is transparent.

- The enamel: This is highly translucent but less so than the EDJ.

For esthetic success, the composite resin must at least reproduce the opacity of dentin and translucence of enamel. Thus, most commercially available composite resin systems have four main components:

- Achromatic enamels

- Universals (often called chromatic enamels)

- Dentin (sometimes called opaque)

- Effect shades

The Layering Sequence

Achromatic Enamels

The achromatic enamels have no chromaticity and high translucency. Chromaticity is the property of hue and chroma combined — hue being the color described (e.g., red-yellow, green, red-purple) and chroma being the intensity or saturation of the color.

Considering a glass of Cabernet Sauvignon, the hue would be red-purple, and the chroma would be high. The chroma would decrease if you drank half of the glass and diluted the remaining wine with water. If you continued to drink and dilute, eventually no wine would remain, and the glass would contain only water — this would have no color and therefore be achromatic.

As the name implies, achromatic enamels have no color. Their nomenclature varies, but they are often referred to as “white enamel”, “incisal,” or “clear.” They are used in areas where high translucency is required to visualize the details of underlying composite masses.

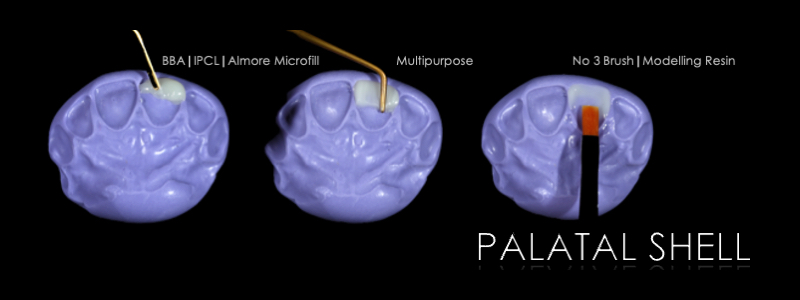

The most common usage is to form a palatal shell in the Class IV situation — this allows the creation of opalescence. Opalescence is the property of exhibiting a milky iridescence like an opal, which is seen as a blue/grey and orange effect on the incisal edge of an unworn incisor tooth.

Keeping the achromatic enamel very thin, around 0.1 – 0.3 mm thick, is critical when building the palatal shell. Thicker shells result in imperceptible detail and a drop in value (i.e., undesirable greyness).

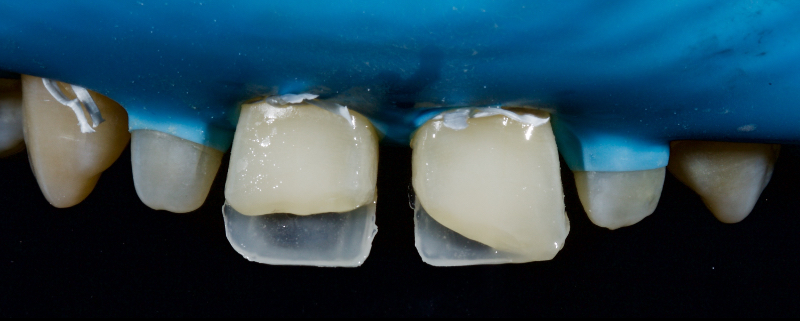

To achieve this, the achromatic enamel mass is first placed on a PVS Putty stent made from a diagnostic wax-up with a flat plastic (see the first article in this series for more detail). The enamel mass is thinned with a flat plastic in combination with a multipurpose condenser, a #3 brush (i.e., GC, Cosmedent, Tokuyama), and some modeling resin (Fig. 7).

A modeling resin is a liquid resin that does not contain HEMA — examples include modeling resin (Bisco), Brush and Sculpt (Cosmedent), and Signum (Kulzer). The unpolymerized resin is then carried in the stent to the tooth and adapted to the palatal margin with a #3 brush (Fig. 8).

Before polymerization, the contact points are cleared with an Interproximal Carver Long (IPCL) like American Eagle (Fig. 9). The resin mass is then polymerized to create a palatal shell (Fig. 10).

The effect shades may be regular packable resin or flowable resin. Commonly used effect shades include:

- Amber/ochre: This effect shade is used to create an incisal edge halo or to increase the chroma of the gingival third.

- White: This effect shade is used for incisal edge halo or for crack lines and “intensive” hypocalcification effects1.

- Blue and grey: This shade is used to create opalescence effects.

- Brown: This shade is used for stained enamel crack lines and fissure tinting of posterior units.

The next step in the Class IV build-up is the realization of an incisal edge halo with either a packable resin on a flat plastic (Fig. 11) or flowable resin on a #1 brush (Fig. 12).

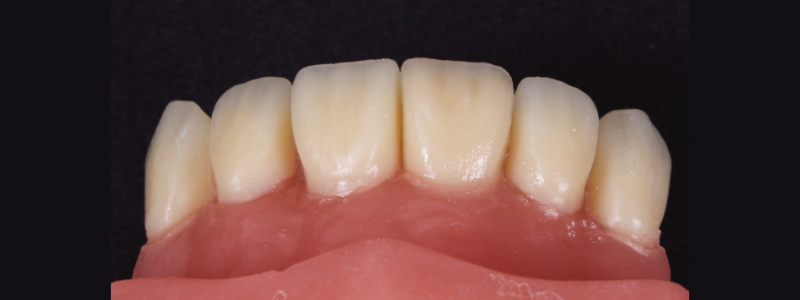

The dentin masses have high opacity and chroma — they mask the transition line between tooth and restoration and increase the value, avoiding a “greyed out” restoration. Essentially, they replace the opacity of natural dentin within the restoration. Failure to employ a dentin mass is the most common reason for layering esthetic failure in a Class IV restoration.

The dentin mass is placed with a flat plastic and extends from the most superior aspect of the infinity bevel (more details in the second article) toward the incisal edge — it finishes around 1-2.0 mm short of the incisal edge. Dentin mamelons may be modeled with a posterior occlusal carver (see Fig. 13).

Inferiorly, the dentin resin mass should not be placed apical to the superior aspect of the infinity bevel since that would result in a visible opaque line in the final restoration. The dentin mass should be under contoured (Figs. 14 and 15).

Universals

The universals — sometimes called chromatic enamels — have chromaticity and translucency between the achromatic enamels and the dentins. They can recreate the enamel surface in the gingival and mid-third of an anterior tooth or in the Class I or II. In terms of shade, they are named as per the VITA system (i.e., A1, B3).

They are placed to overlap the dentin resin masses, finishing at the inferior aspect of the infinity bevel. Since the chromatic enamels have a degree of translucency, the thin layer at the margin hides the restoration margin.

Towards the incisal, dentin mamelons are formed with a posterior occlusal carver (Fig. 16) and then “feathered” with an explorer (Fig. 17). This gives a highly natural appearance.

The chromatic enamels are built to full contour in the gingival and mid thirds but are under contoured in the incisal third (Figs. 18 and 19).

The next phase in the build-up is the application of a blue-grey resin mass in between the mamelon effects to create opalescence (Fig. 20). This should be sparing and confined to the incisal 2-3.0 mm. This layer should also be under contoured.

The final layering phase involves applying an achromatic enamel to the incisal third on the facial surface. This is adapted and smoothed with a flat plastic and a #3 brush/modeling resin (Figs. 21 and 22). The restoration is then polished.

A Clinical Case

In this case, a 23-year-old male presented with Ellis Class II fractures of both central incisors (Fig. 23). He had no interest in closing his diastema or restoring the peg laterals. A treatment plan was agreed upon to restore both central incisors with direct resin.

References

- Vanini, L., & Mangani, F. M. (2001). Determination and communication of color using the five color dimensions of teeth. Practical Periodontics and Aesthetic Dentistry, 13(1), 19-26.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Jason Smithson

Date: August 6, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts