A Comprehensive Guide To Biologic Width

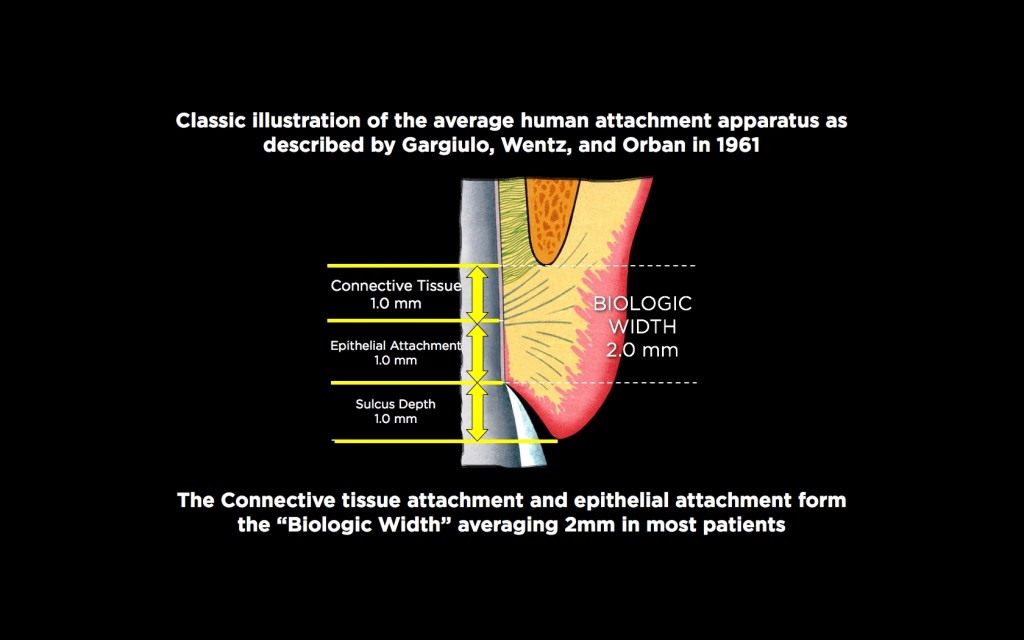

Biologic width describes the combined heights of the connective tissue and epithelial attachments to a tooth. The attachment dimensions were described in 1961 by Garguilo, Wentz, and Orban in a classic article on cadavers. Their work showed that connective tissue attachment has an average height of 1.0 mm, and epithelial attachment also has an average height of 1.0 mm, leading to the 2.0 mm dimension often quoted in the literature for biologic width. In addition, they found the average facial sulcus depth to be 1.0 mm, leading to a total average gingival height above bone of 3.0 mm on the facial.

The Term Biologic Width

For historical accuracy, it is interesting to note that Garguilo, Wentz, and Orban didn’t use the term biologic width in their 1961 article; the actual name, biologic width, came from Dr. D Walter Cohen at the University of Pennsylvania in 1962.

In 1994, Vacek conducted further cadaver studies on biologic width, which helped give some insight into the clinical findings many of us had seen. He found that biologic width was relatively similar on all the teeth in the same individual, from incisors to molars, and around each tooth. He also found the average biologic width to be 2.0 mm, as the Garguilo group did. What Vacek found clinically meaningful was that biologic width varied between individuals, with some having biologic widths as small as 0.75 mm, and others as tall as 4.0 mm. Still, statistically, the majority followed the 2.0 mm average.

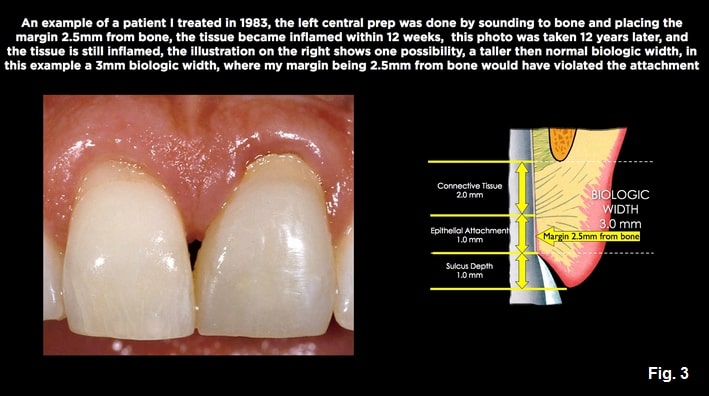

The primary significance of biologic width to the clinician is its importance relative to the position of restorative margins and its impact on post-surgical tissue position. We know that if a restorative margin is placed too deep below tissue, so that it invades the biologic width, two possible outcomes may occur.

First, there may be bone resorption that recreates space for the biologic width to attach normally. This is the typical response seen in implants to allow the formation of a biologic width, the so-called funnel of bone loss to the first thread.

Secondly, gingival inflammation is the most common response to a biologic width violation around teeth, a significant problem with anterior restorations.

The importance of biologic width to surgery relates to its reformation following surgical intervention. Research shows it will reform through coronal migration of the gingiva to recreate not just the biologic width, but also a sulcus of normal depth. This means if the surgery doesn’t consider the dimensions of biologic width when placing the gingiva relative to the underlying bone, the gingival position won’t be stable, but instead will migrate in a coronal direction. This example also strongly influences when and where restorative margins should be placed post-surgically.

Restorative Margin Placement

I also mentioned the two possible outcomes if a restorative margin is placed too close to bone: bone loss and gingival inflammation, with the inflammation being far more common.

Your Options and Biologic Width

The first option to consider when placing a restorative margin is whether it can be left supra or equigingival or must be placed subgingival. If the margin can be placed supra or equigingival, the concerns over biologic width don’t exist — assuming the gingiva is healthy and mature.

Today, if the tooth color is acceptable and there is no structural reason to extend below tissue (such as caries, cervical erosion, old restorations, or a need to extend for ferrule), a translucent material, such as lithium disilicate, can achieve an esthetically acceptable result without the need to go below tissue.

Sometimes, it’s necessary to place margins below tissue, specifically if structural issues exist, the tooth is extremely discolored, or you need to use a more opaque restoration such as zirconia or metal ceramics. In these instances, a subgingival margin is necessary and the concern of going too far below tissue and violating the attachment exists.

When I believed biologic width was the same for every patient (the 2.0 mm described by Gargiulo in 1961), I thought the solution to margin placement was simple: place the margin 2.5 mm from bone. This would be far enough away from bone that it would not violate the attachment, but also leave the margin subgingival, as the facial gingival margin is normally at least 3.0 mm above bone.

The truth was the 2.5 mm distance worked well for most patients; I would use a perio probe and sound to bone to be sure my margin was, in fact, 2.5 mm away from the bone as I prepped. But in many patients, the gingiva became very inflamed following treatment.

The reason was related to what Vacek found in 1994: “Biologic width is not the same between patients, some having attachment heights as tall as 4.0 mm.” In these patients, my 2.5 mm distance from bone was in their biologic attachment.

Where we really want a subgingival margin is actually easy to describe. We want it below the gingival margin, but above the epithelial attachment — in the sulcus, if you will. The key, though, is we can’t use bone consistently as a reference unless we actually know that individual patient’s attachment height.

Possible Gingival Presentations

I’ll now describe the two types of gingival presentations we encounter when approaching subgingival margin placement and the risks of each. Whenever I contemplate placing a subgingival margin, I start by probing the facial sulcus of the teeth where I will place the restorations.

Biologic Width: Possible Gingival Presentations

It’s essential to realize that when we probe the sulcus, it routinely enters the epithelial attachment 0.5 mm, meaning the actual sulcus is typically 0.5 mm less than the probed depth. The probe penetrates even deeper into the attachment in patients with inflamed tissue.

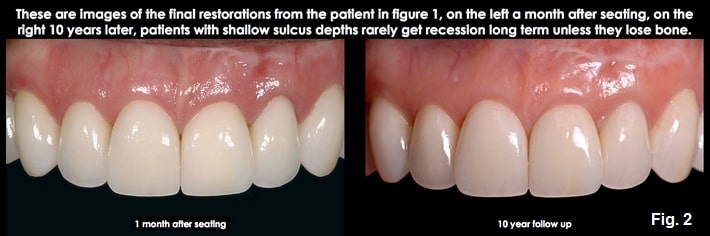

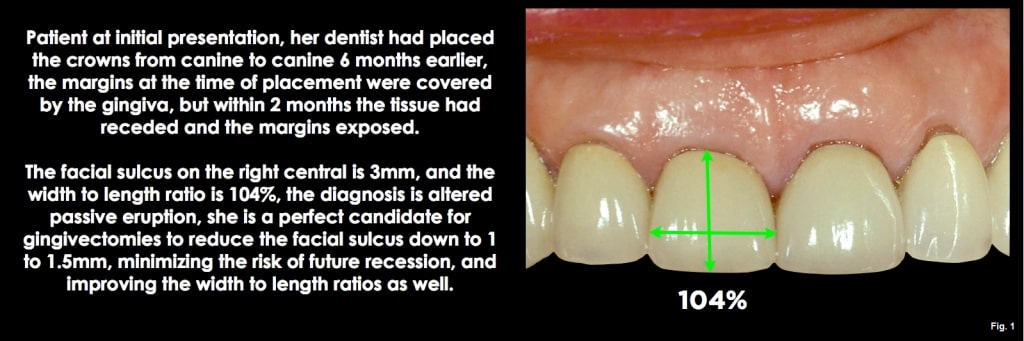

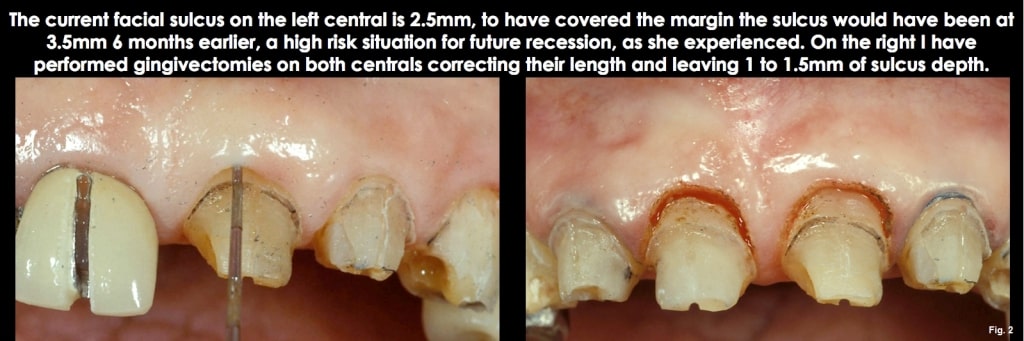

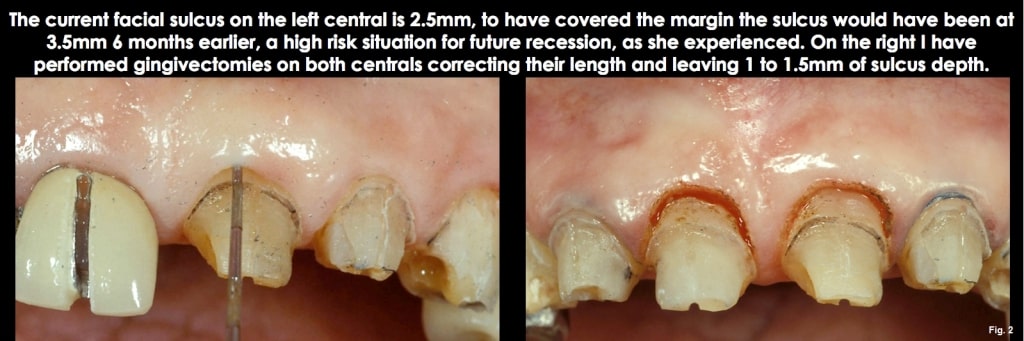

In patients with normal or shallow facial sulcus depths, typically 1.0 mm to 1.5 mm, the risk in subgingival margin placement is going too deep and violating the attachment, as the histologic sulcus depth is probably less than 1 mm. The good news is these patients do not typically present a high risk of recession following placement of the restoration, since the gingival dimension above bone is commonly 3.0 mm on the facial (similar to the Gargiulo diagram in my previous articles). This means there would have to be bone loss for the tissue to recede apically. So, going below tissue by more than 0.5 mm to 0.7 mm is unnecessary, and the margin will unlikely violate the attachment or be exposed to future recession. (Figs. 1 and 2)

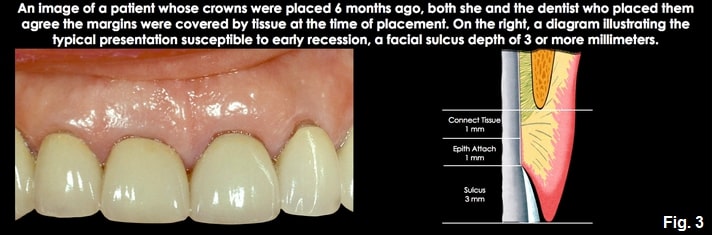

The second presentation is a patient with much deeper facial sulcus depths, 2.0 to 4.0 mm or more. This patient presents a much higher risk of recession following restoration unless the margin is placed farther below tissue. The risk of recession is because there are several millimeters of unattached gingiva above the biologic width. The thickness of the unattached tissue influences the risk of recession; the thinner the tissue and the deeper the sulcus, the greater the risk of recession. The good news is that it is tough to violate the biologic width on these patients, as you would need to prep 2.0 to 4.0 mm below the gingiva to reach the attachment.

In subsequent articles, I’ll describe the options and steps to manage these different presentations.

Subgingival Margin Placement in Shallow Sulcus Patients

In patients with sulcus depths less than 1.5 mm, the risk of subgingival margin placement is going too deep and violating the attachment. For these patients, my goal for margin placement (if a subgingival margin is necessary) is to place the margin 0.5 mm to 0.7 mm below tissue. This protects the attachment but still leaves the margin covered by gingiva. Since the risk of recession is low, the 0.5 mm to 0.7 mm subgingival placement hides the margin visually.

The steps I take to achieve the correct subgingival margin placement are as follows:

Step 1

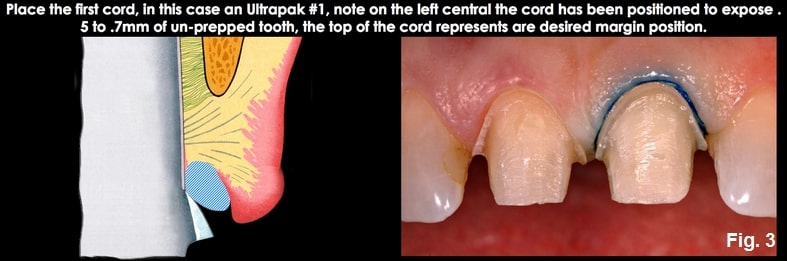

Prep the tooth completely to the existing gingival margin level, leaving only the subgingival margin placement to be completed. (Fig. 3)

Step 2

Probe the sulcus and identify that the probing is 1.5 mm or less. (Fig. 4)

Step 3

I am a fan of retraction cords for controlled subgingival margin placement on anterior teeth, even though many clinicians prefer not to use them. I would now place an Ultradent, Ultrapak cord, #00 (thin tissue) or #1 (most tissue). The key is that the cord is placed 0.5 mm to 0.7 mm apical to the prep margin, which was left at the height of the gingival margin. The cord is damp, not soaked, with aluminum chloride solution. (Fig. 5)

Step 4

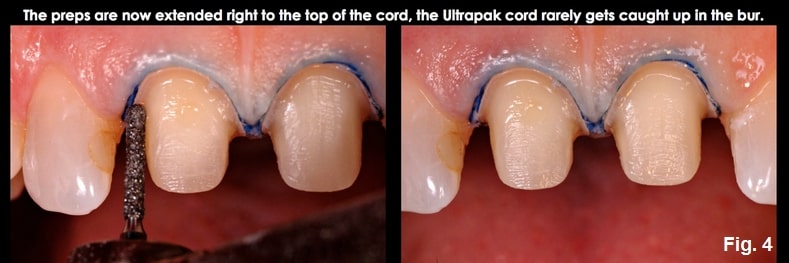

The first cord retracts the tissue and represents the correct position for the final prep margin, 0.5 mm to 0.7 mm subgingival. Prep to the top of the cord using the bur that provides adequate depth and shape for your finish line. (Fig. 6)

Step 5

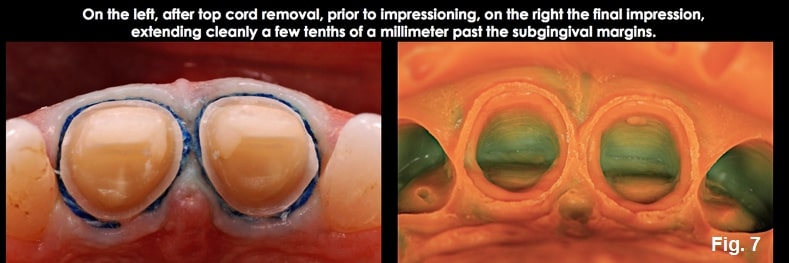

Place a second layer of cord, pushing it apically so it sits at the level of the prepped margin. If you can’t see the second cord layer, it has been placed too deeply; you want to visualize the second cord all around the tooth. (Fig. 7)

Step 6

Wet the top cord with water, remove it, air dry, and impress, traditionally or optically. (Figs. 8 and 9)

Step 7

Completed restorations (Fig. 10).

Margin Placement for Deep Sulcus Patients

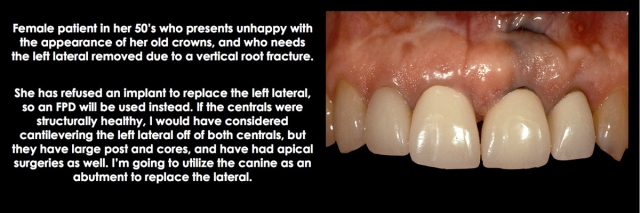

I’d like to present what options exist when we are faced with placing restorations on patients who have deeper facial probing depths (greater than 2.0 mm). The challenge in these patients is the risk of future recession due to the amount of unattached tissue above the biologic width. The facial sulcus depth and the tissue’s thickness affect the risk. A patient with a 3.5 mm facial sulcus and thin tissue is at greater risk of recession than a 2.0 mm facial sulcus and thick tissue.

When I am going to restore anterior teeth, and the facial probing depths are greater than 2.0 mm, the first thing I do is attempt to identify why, which generally comes down to one of two options.

Option one is altered passive eruption. The gingiva has not receded to a normal position relative to the bone and CEJ. The hallmark of this is the appearance of the teeth, which have a short clinical crown length. If one measures the width-to-length ratio of central incisors with altered passive eruption, the ratios may be in the 90% to 100% range, or even higher, as opposed to the more normal 75% to 80%.

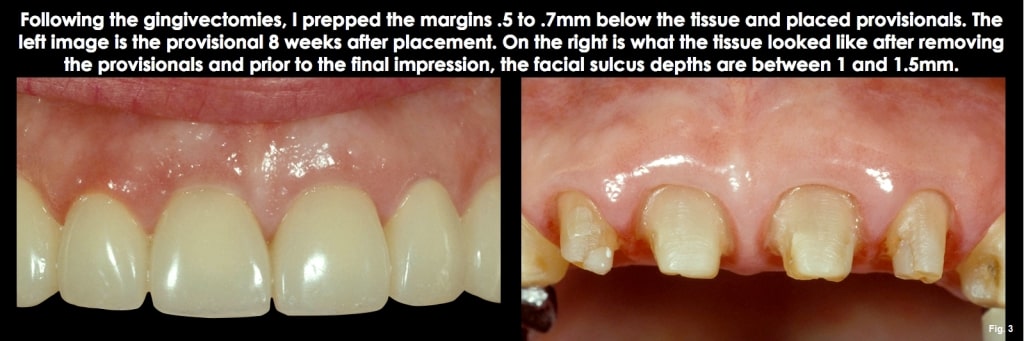

The good news about a diagnosis of altered passive eruption is that the deep sulcus can be eliminated with a gingivectomy. This eliminates the risk of future recession by leaving a normal 1.0 mm to 1.5 mm sulcus depth, and it also improves the length of the clinical crowns at the same time. To use a gingivectomy, though, performing it across all the anterior teeth is typically necessary so that the gingival levels flow correctly from canine to lateral to central. (Figs. 11-13)

If considering a gingivectomy, the other key is never to remove so much gingiva that the remaining sulcus is less than 1.0 mm in depth, as the tissue will grow back if you do.

The second option for a deep facial sulcus is bone loss and a lack of recession, effectively created by the attachment migrating apically with the bone loss. Still, the gingiva does not follow a pocket formation, if you will. The clinical crown lengths in these patients are typically normal, so eliminating the deep sulcus with a gingivectomy would create excessively long and narrow clinical crowns.

These patients are typically a greater risk to restore than the altered passive eruption patients, as the sulcus depth can’t be easily reduced with a gingivectomy to minimize the risk of recession.

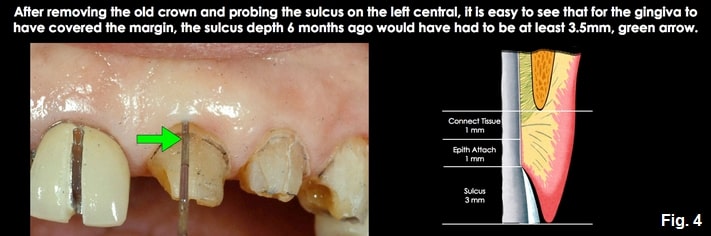

Margin Placement For Deep Sulcus Patients

I’ll now present a more challenging problem: the patient with deep facial sulcus depths, but a gingiva at an ideal position. This means that the use of a gingivectomy to reduce the sulcus depth will result in the clinical crown appearing too long. This is typically a patient who has had some facial bone loss and apical migration of the attachment, but no subsequent recession of the gingiva.

You generally have two options with these patients to reduce the risk of exposed margins from future recession. The first, often best option, is to place your margin supragingival, not inducing any trauma to the gingiva. This can be readily accomplished if translucent all-ceramic materials can be used, especially if the existing tooth color is acceptable. Any future recession isn’t noticeable, as the margin was already above tissue. If you must go below tissue because of a discolored tooth, or because you need to use a more opaque restorative material (metal ceramics or zirconia, for example, in the case of an FPD), the risk of future margin exposure is definitely a risk.

My approach in these instances is to place the margin below tissue, half the depth of the probing. So, for a 3.0 mm facial sulcus depth, I would place the margin 1.5 mm below tissue. This minimizes the risk of margin exposure if a recession occurs, but it can’t completely prevent the risk.

Remember, violating the attachment is not a risk in these deep sulcus patients, like in shallow sulcus patients. Therefore, going half the depth of the sulcus below tissue is biologically acceptable, but the challenge is how to do it without overly traumatizing the tissue.

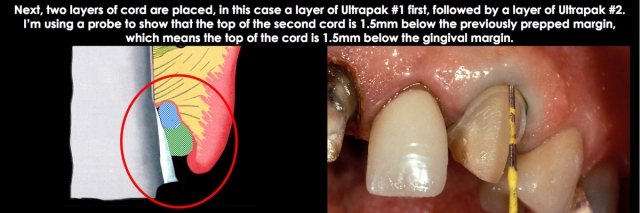

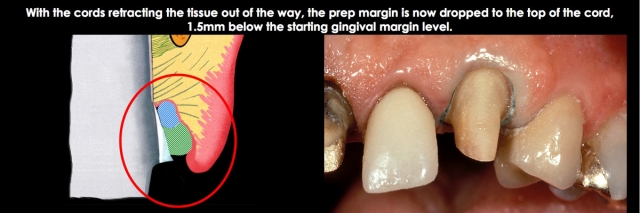

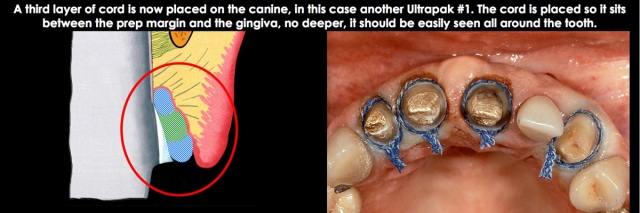

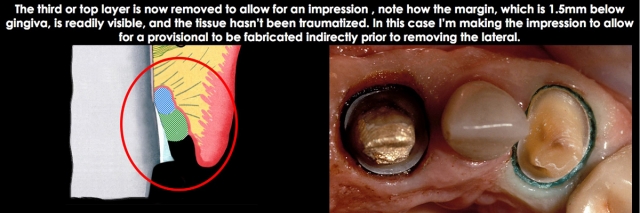

The case I am including will show you the step-by-step approach I use to place the margin at the correct depth, and protect the tissue at the same time:

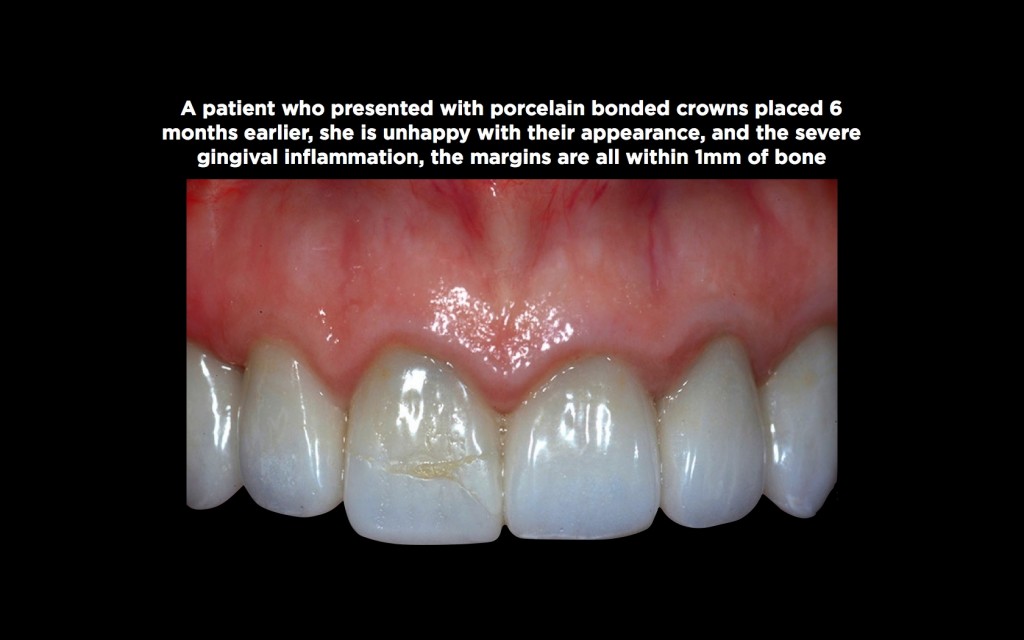

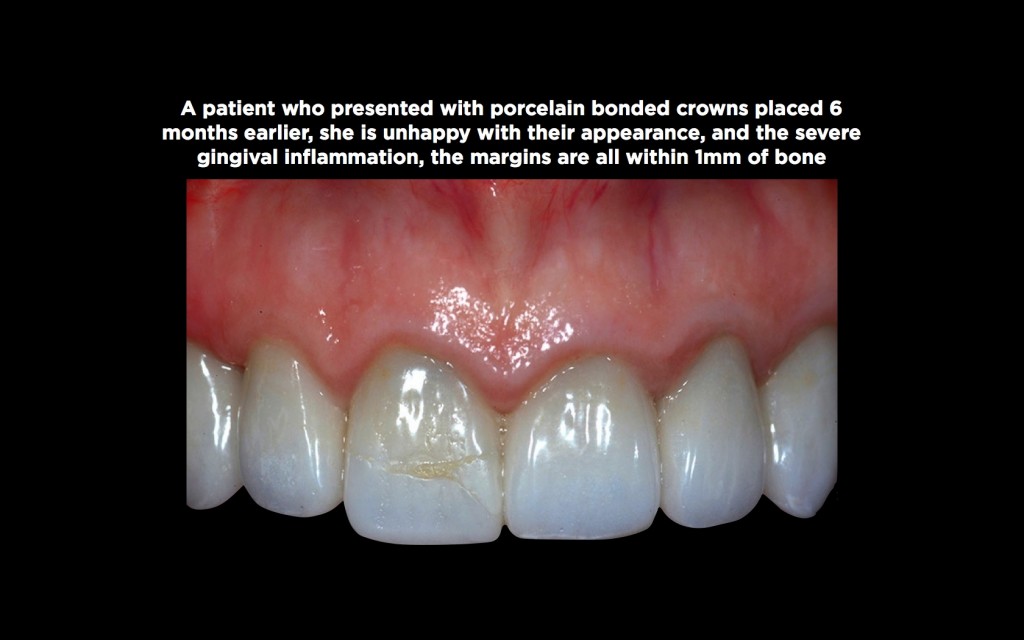

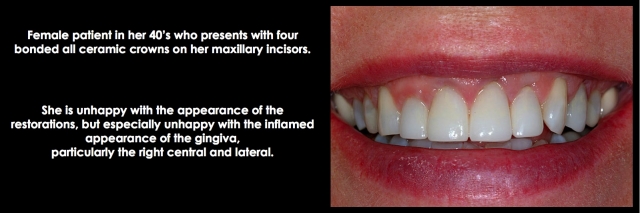

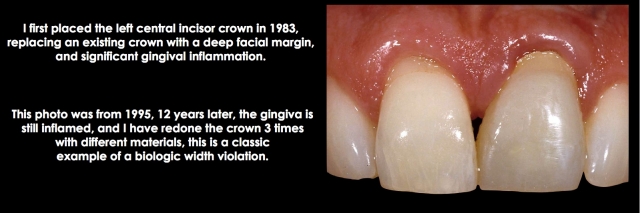

Diagnosing a Biologic Width Violation

I will start to address how to diagnose inflammation around restorations that exist because the margins have been placed too deeply, violating the attachment. When we see an anterior restoration, particularly a full crown, that has significant gingival inflammation, a series of possible diagnoses exists:

- It could be plaque control (but if the adjacent teeth have healthy gingiva, that is unlikely).

- It could be marginal fit, which can be examined with an explorer and radiograph.

- It could be poor contour, preventing adequate hygiene (again, possible to examine).

- It could be an allergic response to the restorative material — especially if the restoration was done in the ’80s or ’90s using a nickel-containing alloy, and the patient is female.

- But it could be because the margin is placed too close to bone, violating the biologic width. (See Figs. 14–16 below)

Ideally, if the existing restoration is removed, and a well-fitting temporary is placed for at least three months without the return of any gingival inflammation, you would assume the margin location was not the problem, and one of the other etiologies applied. The three-month wait is because it is not unusual to damage the attachment apparatus when removing an old restoration and placing a temporary restoration.

You may see perfectly healthy-looking tissue until it heals and matures, usually between eight and 12 weeks, and then the inflammation returns. Of course, not every patient wants you to take off their restoration to make a diagnosis, so here are some other options to assist in deciding whether or not the margin location is the problem:

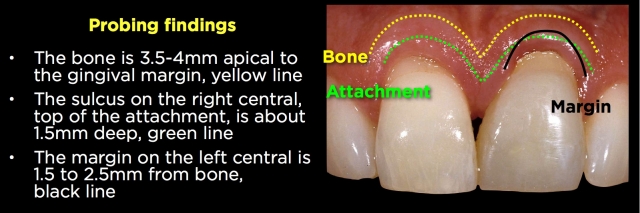

- First, simply place a perio probe in the sulcus until it reaches the margin. Do this circumferentially around the tooth. What you are looking for is pain: a margin in the sulcus will result in no response, a margin in the connective tissue attachment will be painful to probe.

- Next, anesthetize the tooth you are concerned about. Place the perio probe on the restorative margin and read the distance from there to the gingival margin. Keeping the probe against the root laterally, slide the probe down to the bone, allowing you to compare the previous probe readings with those taken when the probe is on bone.

- Third, use a periapical radiograph; while it won’t let you see the margin location relative to bone on the facial, it will on the interproximal.

If the margin is painful to probe, within 2.0 mm of the bone when measuring it, or on a radiograph, you probably have a biologic width violation. The only way to eliminate the inflammation is to correct the problem.

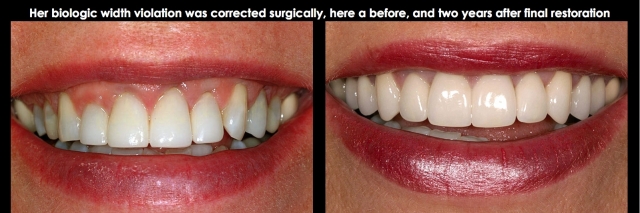

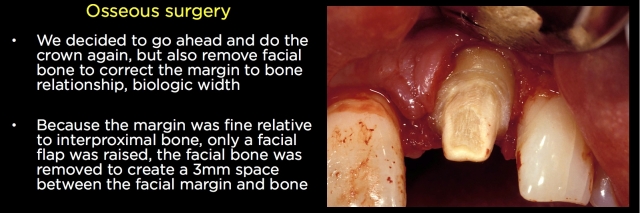

Surgical Correction of a Biologic Width Violation on the Facial Surface Only

When a restorative margin is placed too close to bone, gingival inflammation occurs. The only solutions to eliminate the inflammation are to move the margin away from bone or move the bone away from the margin. In most instances, the classic measurements from Garguilo, Wentz, and Orban would be used for the correction; in other words, create 2.5 mm to 3.0 mm of space between the margin and bone.

There are two ways to move the margin away from bone: orthodontic extrusion, and the other is so-called “root reshaping,” where the old margin is smoothed away and a new margin is prepped at a more coronal and correct level. This approach can be beneficial when the previous tooth preparation was done with minimal tooth reduction. Still, it’s much more difficult if a heavy chamfer or shoulder has been previously prepared.

The common solution for biologic width violations is to move the bone away from the margin with osseous surgery. The challenge with the osseous surgery is the risk of recession occurring. If you were dealing with a single central incisor with a margin placed too deep on the direct facial, surgery would be my first choice — lay a facial flap, remove the necessary facial bone, and replace the flap to its original position.

If the tissue is normal in thickness, it is rare to see much (if any) recession. The risk is higher if the tissue is thin, but it is always possible to come back with a connective tissue graft to cover the root and margin.

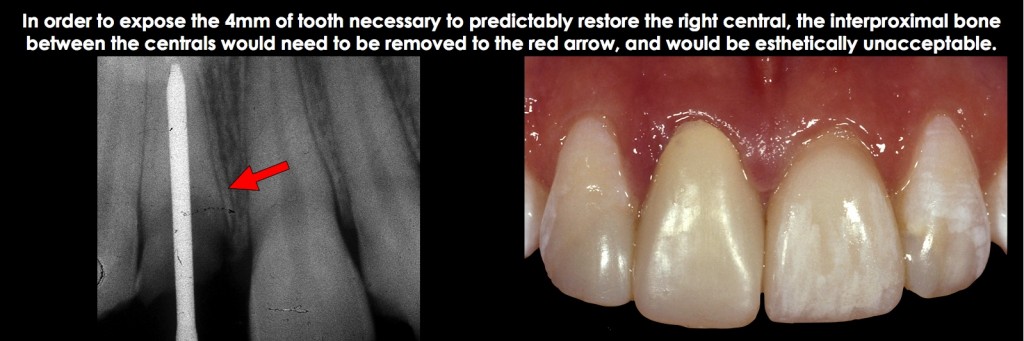

The real challenge is dealing with a single central restoration with a biologic width violation on the interproximal. Now, if you remove bone to correct the violation, there is a much higher incidence of getting some loss of papilla and opening of the gingival embrasure.

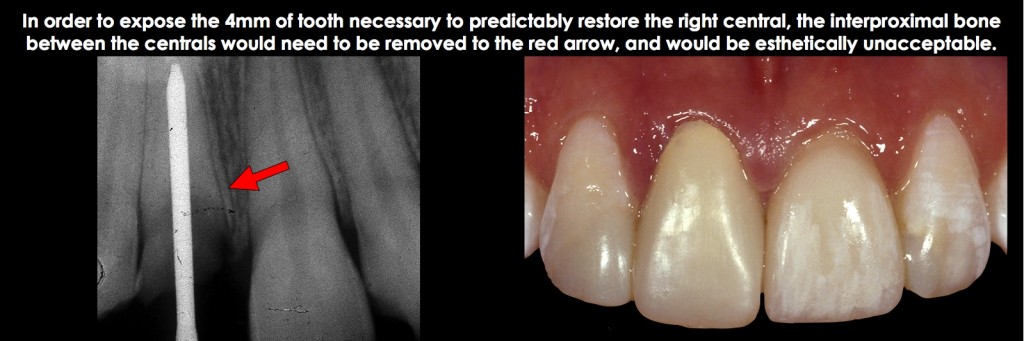

Managing Interproximal Biologic Width Violations on Single Anterior Teeth

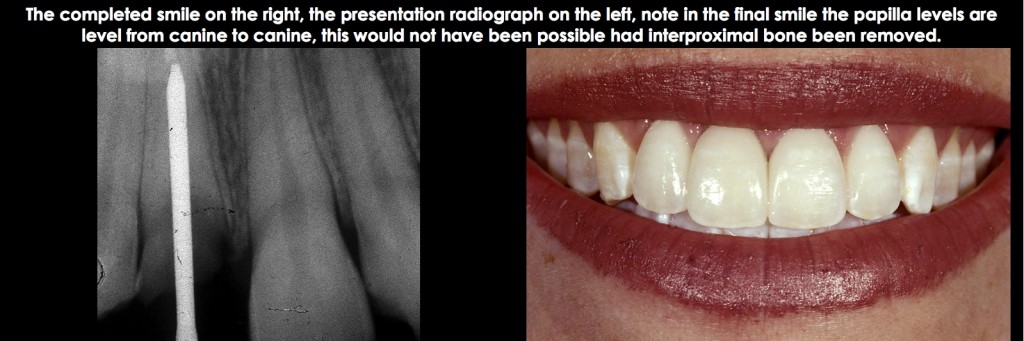

Osseous surgery is rarely indicated for correcting an interproximal biologic width violation on a single anterior tooth because it requires removing interproximal bone, which is followed by a loss of papilla height and an open embrasure. Instead, orthodontic extrusion is the ideal treatment to expose adequate tooth structure for restoration and for ideal esthetics with no loss of interproximal papilla height (Figs. 17 and 18).

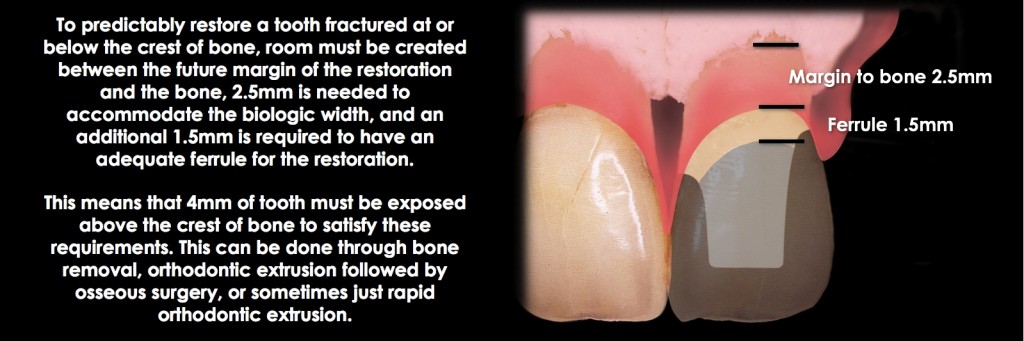

Remembering the desired outcome for correcting the biologic width violation (the margin of 2.5 mm from bone) is important. If it is a tooth with endo and a post and core, an additional 1.5 mm of tooth structure is exposed for adequate ferrule. So, for teeth with endo, post, and cores, 4.0 mm of tooth structure must be exposed coronal to the bone (Fig. 19)

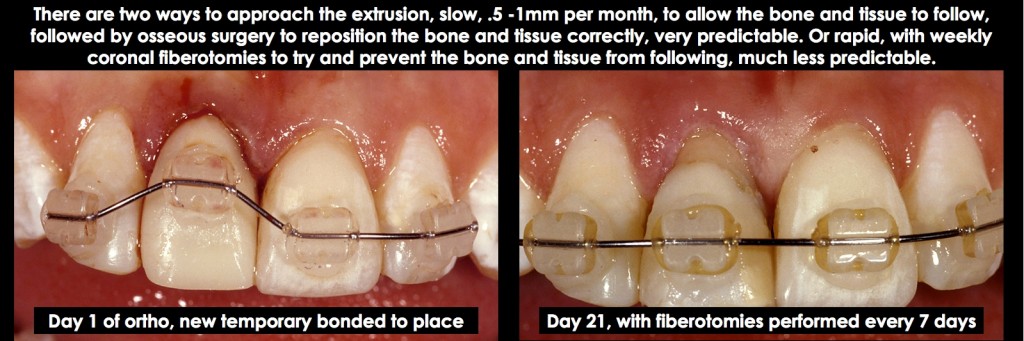

There are two ways to accomplish the extrusion:

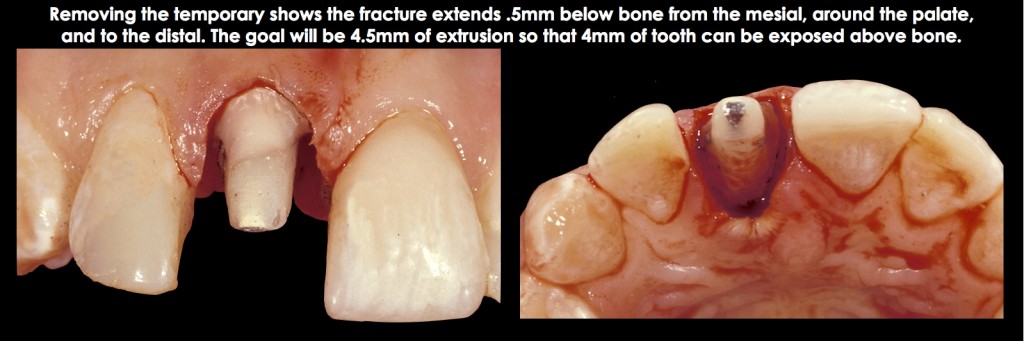

- Slow extrusion of 0.5 to 1.0 mm per month allows the bone and gingiva to follow the tooth. This is followed by osseous surgery to reposition the bone and gingiva, ideally exposing the tooth. This approach is highly predictable and generally chosen, primarily when other orthodontic concerns exist.

- The second approach, which is normally chosen only when a single tooth needs treatment (i.e., no other orthodontic needs or other teeth with biologic width violations adjacent to the tooth you desire to treat), is to use rapid extrusion, generally all of the movement within four weeks. The key to this approach is to perform supracrestal fiberotomies weekly, to discourage the bone and gingiva from following. However, it’s necessary to retain the tooth in position for at least 12 more weeks to prevent re-intrusion and to evaluate if osseous surgery is necessary due to the bone and gingiva creeping in a coronal direction (Figs. 20–23).

Finally, in all cases where forced extrusion is used to resolve a biologic width violation, the amount of root in bone is reduced by the amount the tooth is being extruded. While clinicians often worry about keeping a 1:1 crown-to-root ratio at a minimum, my experience has been that leaving 8.0 to 9.0 mm of root in bone has provided a successful long-term solution.

Managing Facial and Interproximal Biologic Width Violations on Multiple Adjacent Teeth

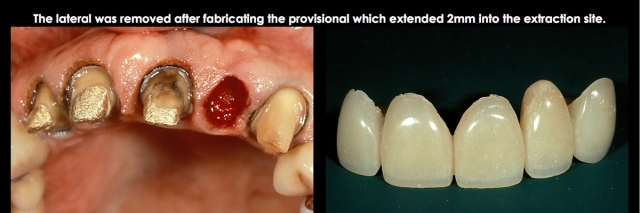

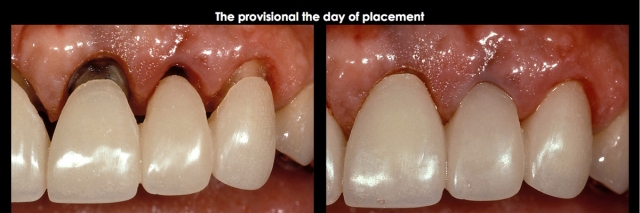

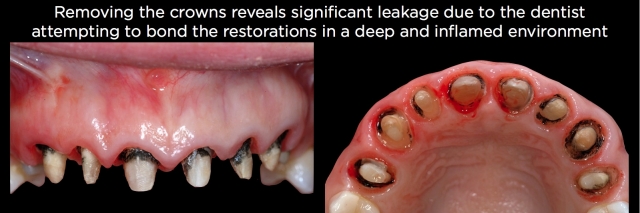

Patients with multiple adjacent existing anterior crowns, prepped essentially to bone, are some of the most challenging esthetic cases to treat. There is usually significant gingival inflammation, and if the crowns were bonded, there is often significant black staining from the bacterial growth that occurs when attempting to bond in a highly contaminated environment, heaviest in the cervical 1/3, and showing through the translucent crowns (Fig. 24).

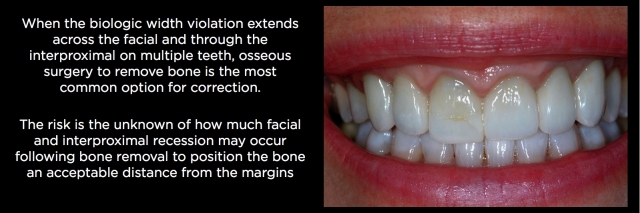

The only solution I have found successful in these cases is to start by addressing the biologic width problem: the margins being too close to bone. This is done with osseous surgery by correcting the bone-to-margin distance. Bone removal creates the risk of recession, and this risk is especially high when bone has to be removed on both the facial and interproximal (Fig. 25).

For these patients, my first step is to remove the old crowns to visualize each tooth’s quality and assess the distance from the margin to the bone using a probe that is 360 degrees around the tooth. Additionally, it lets me see how heavy the prior tooth reduction was and if the reduction at the margin was minimal. For example, with a slice-type finish line, minor “root reshaping” is often possible by smoothing out the old margin. This must be followed by re-prepping a new margin and the correct distance from bone, eliminating the need for bone removal. Bone removal becomes mandatory when the preps are heavy shoulders or chamfers (Fig. 26).

The amount of bone removal is dictated by how close the existing margins are to the bone and whether all the teeth were prepped the same. As a rule, I would move the bone 2.5 to 3.0 mm away from the existing margins all the way around the teeth to accommodate the biologic width. It would be unusual for a patient to need more space than that (Fig. 27 and 28).

At the time of suturing, assuming the pre-treatment crown length was acceptable (i.e., no crown lengthening was desired), the flap should be replaced exactly where it was pre-surgically, not apically positioned. The goal is to hope for a longer attachment apparatus rather than a deeper pocket, followed by recession (Fig. 29).

I often get asked how long to wait following healing before proceeding in these patients. Remember, this is not a typical crown lengthening case — the bone has been moved apically, but the tissue has not, so the risk of recession is much higher. Also, we are usually treating a patient who is unhappy about the need for the treatment. I typically wait at least six months before proceeding (Fig. 30).

Depending upon the patient’s gingival thickness, it can be surprising how often no recession occurs on the facial or interproximal, even when 2.0 mm of bone has been removed around the teeth (Figs. 31 and 32).

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Frank Spear

Date: June 28, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts