Managing Cracked Teeth: An Enigma Wrapped Up Inside a Riddle Asking Questions

Without a doubt, one of the most significant challenges facing the preventive restorative dentist today is how to manage a cracked tooth. If you put any group of dentists in a room and pose a single question about how a tooth with a crack should be managed, you’ll end up with a spirited discussion with no resolution.

Further complicating the problem, it is difficult to determine a prognosis for a cracked tooth. In fact, if any interested dentist reading this article is honest, they’ll acknowledge they have lost at least one (and probably several) patients from their practice because of how they proposed to manage a cracked tooth.

I am no different: I can recall this case that presented to my office several years ago: a 45-year-old healthy and active woman with the chief complaint of “My upper right teeth are all sensitive whenever I eat.”

There was neither periapical nor periodontal pathology; the joints could be loaded without pain with a leaf gauge and the muscles were asymptomatic. But during a clinical exam, there was a shift of approximately 0.5 mm from a stable and reproducible condylar position to maximum intercuspation toward the right, consistent with eccentric “stripes” on the buccal cusps made with articulating ribbon, measured at the midline (Fig. 1).

What would you have recommended? I recommended an occlusal work-up with mounted study models that likely would have led to an occlusal equilibration followed by cuspal coverage indirect restorations.

The patient went back to her original dentist (who restored the Cusp of Carabelli on the first molar, by the way), telling me on her way out the door that I was “too aggressive.”

During an informal conversation with the patient a few years later, she was all too willing to tell me how she no longer had pain when she was chewing, but asked if I had any thoughts about why her unilateral maxillary removable partial denture wasn’t staying in! I wonder: Is it more conservative to do a thorough diagnosis and crown a few teeth, or to extract teeth when they crack beyond the point of no return and replace them with a removable partial prosthesis that will require replacement multiple times during the course of her lifetime? (I apologize for my sarcasm.)

While I don’t agree with the other dentist’s approach to management of the edentulous space left by the loss of the cracked tooth, nor can I excuse the failure to recognize traumatic occlusion, I can’t necessarily fault the decision not to restore the teeth with cuspal-coverage restorations. Quite frankly, significant high-level research does not exist in the literature at the time of this writing.

Classification of cracked teeth

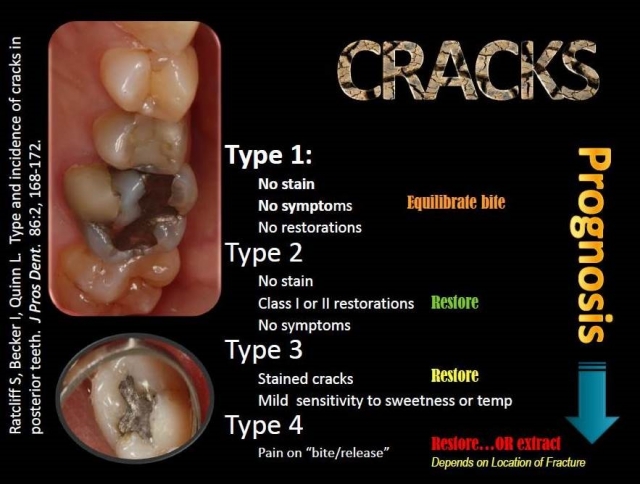

There are several position statements by some special interest groups about how to manage cracked teeth, and there are some decent observational research projects on the subject, including one published by Dr. Steve Ratcliff, a Spear Resident Faculty member.1

In fact, I have used Dr. Ratcliff’s article to classify cracks in my practice for several years. The system — or at least my rendition of the Ratcliff classification system — helps me identify, track, and treatment-plan cracked teeth and educate patients about the progress of the cracks should they choose to “watch and see what happens” over time. I have constructed an illustrated slide of this system and hang a laminated printout on the wall in each operatory for quick reference and patient education.

While this classification system is a valuable tool, there are some challenges with it.

- For example, there’s no classification for a crack present in a virgin tooth that extends to dentin, so in my practice, I’ve added the classifications “2a” and “3a” to take this into consideration.

- It doesn’t characterize cracks as complete or incomplete, as some other articles on cracks do, and it doesn’t offer a distinction about whether a crack extends onto the root surface or where it stops.

- There is also the challenge of the oblique fracture that undermines a cusp without symptoms or contact with a restoration, for which I have used the term “4a.”

With these modifications, it seems to work well (at least for me in my practice).

Calibrating how and when cracks should be treated

Much of the general disagreement about how and when cracks should be treated has to do with the problem of human research trials — having enough people who are willing to gamble with tooth pain from fractures, and an adequate number of calibrated general clinicians to gather objective data over a lengthy period of time in a double-blind fashion.

I’m happy to report that such a hallmark study is currently under way! The National Dental Practice Based Research Network is conducting a four-year study of cracked teeth and how they’re managed, evaluating patient-reported factors such as known bruxism, the type of teeth affected, and the characteristics of individual cracks. The results from the baseline were recently published.2 In the study, teeth with cracks are identified and catalogued by participating dentists practicing all over the United States. The following facts about identified teeth are recorded and catalogued for future reference:

- Number of cracks

- Location of cracks

- Whether cracks connect with each other or with an existing restoration

- Whether the tooth is opposing a natural tooth, no tooth, or a prosthetic tooth

- Whether the crack blocks light during transillumination

- Whether the tooth is selectively pressure-sensitive (for example, with a Tooth Sleuth)

- How the tooth responds to vaporized coolant on a cotton applicator (for example, Endo Ice)

- Radiographic findings or lack thereof

- Presence of caries on the cracked tooth

- Gingival recession

Once a tooth has been identified and data has been recorded, the clinician then reports their recommendations for treatment: restore, observe, perform endodontic therapy, or extract. When and if a tooth in the study is treated, the investigator collects further data focusing on the internal presentation of the fractures in the tooth. Once a tooth is restored, it remains in the study; if it requires extraction, it obviously ceases to be study-applicable.

The initial study results show some interesting baseline findings, looking at 2,975 cracked, vital teeth collected by 209 independent evaluators. For example, molars that have a distal crack that blocks light on transillumination for bruxers have the greatest likelihood of having pain or hypersensitivity.

Interestingly, the NDPBR researchers observed that noncarious cervical lesions, stained cracks, and exposed root surfaces were not significantly associated with symptoms in cracked teeth. Generally speaking, cracks that block light transmission, the presence of caries or wear facets, and distal cracks showed the highest likelihood of being associated with symptomatic cracked teeth. While the authors of this particular study did not make any treatment suggestions or observations at this time, it would be reasonable to conclude practically that teeth with distal cracks and cracks that are positive for transillumination should be seriously considered for priority cuspal coverage restoration.

There are many methods for assessing and diagnosing fractured teeth. One article suggests the following methods.3

- Dental history

- Subjective reports from the patient

- Direct clinical inspection (magnification preferred)

- Tactile evaluation with a sharp explorer

- Vitality testing

- Selective bite pressure evaluation

- Staining with caries detector or other dye

- Transillumination (blocked light suggests fracture into dentin)

- Response to wedging forces

- Exploratory surgery (e.g., removal of restoration or surgical flap)

- Periodontal probing (cracks may have localized pocketing)

Considerations for different approaches to restoring cracked teeth

If cracks are diagnosed, a decision needs to be made as to how to best manage it. The Ratcliff paper provides one logical approach to restorative solutions. In an online course available to Spear Education members, Dr. Frank Spear illustrates an excellent rationale for different restoration approaches, including onlaying cusps instead of internally bonding cusps together,.

However, even with excellent restorative dentistry, some cracked teeth still fail, and some cracks can simply not be diagnosed until it is too late.

Here is a case in point: A long-term patient with an endodontically treated molar managed with a clinically acceptable crown presents with a new periapical asymptomatic lesion (Fig. 3). The diagnosis, based on radiographic and clinical history, is a recurrent periapical abscess due to microleakage. The tooth is adequately re-treated by a skilled endodontist and restored.

Less than 12 months later, the tooth develops a localized distal 9 mm periodontal pocket with bleeding on probing (Fig. 4). Upon extraction of the tooth, the diagnosis of a vertical distal root fracture is confirmed by direct observation under magnification. Therefore, it’s important to consider the possibility of occult root fractures being present whenever restorative dentistry is planned.

suggests a vertical fracture, combined with a localized 9 mm periodontal pocket.

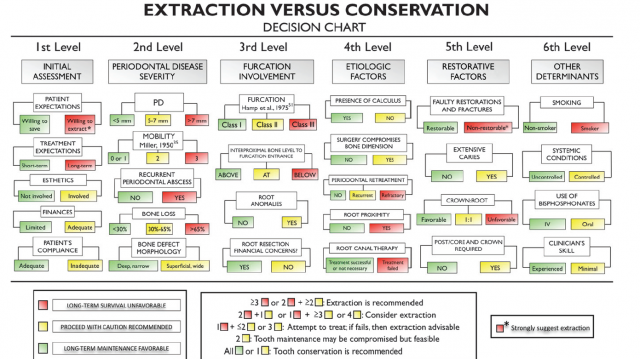

Some clinicians may favor extracting cracked teeth because of their nebulous prognoses, while others may try to save asymptomatic cracked teeth for as long as possible with restorations.

In dental school, I was taught to place a provisional crown on a cracked tooth and observe it for six months before restoration. This recommended treatment must have been based on some form of clinical experience, because I haven’t seen research to recommend or refute this course of treatment. Avila and colleagues,4 meanwhile, have proposed a decision tree for determining whether a cracked tooth should be retained or extracted (Fig. 5):

Given the enigma of cracked teeth, what’s the appropriate treatment plan if cracks are identified? The answer can be developed using the evidence-based dentistry model. It’s important to remember that when practicing evidence-based dentistry, there are three important factors involved in the process:

- The patient’s desires based on adequate informed consent

- The clinician’s skill and expertise

- Available current research.

The articles cited here provide a solid basis to assist in developing an evidence-based treatment plan, but more high-level research is needed. In the meantime, the clinical experience of the clinician cannot be undervalued.

References

- Ratcliff S, Becker I, Quinn L. Type and incidence of cracks in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2001; 86:168–72.

- Hilton T et al. Correlation between symptoms and external characteristics of cracked teeth: Findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA 2017; 148(4):246–256.

- Rivera E, Walton R. Cracking the cracked tooth code: Detection and treatment of various longitudinal tooth fractures. A Endodontics: Colleagues for Excellence. Summer 2008; Bonus Material G

- Avila G et al. A novel decision-making process for tooth retention or extraction. Periodontol. 2009; 80:476–491.

VIRTUAL SEMINARS

The Campus CE Experience

– Online, Anywhere

Spear Virtual Seminars give you versatility to refine your clinical skills following the same lessons that you would at the Spear Campus in Scottsdale — but from anywhere, as a safe online alternative to large-attendance campus events. Ask an advisor how your practice can take advantage of this new CE option.

By: Kevin Huff

Date: July 12, 2017

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts