Ideal Position of the Central Incisor

Facially generated treatment planning: What is the ideal position of the central incisor in three planes of space?

Goals are critical in interdisciplinary treatment planning. As a team, how do we determine the ideal position of the central incisor? What are the critical parameters? Do we look at the teeth relative to one another? Relative to the bone and soft tissue? Relative to the base of the skull? Relative to the face? Why are specific parameters important? This article will outline the central incisor’s ideal position in three space planes: vertical, anterior/posterior, and angulation.

Historically, we have always considered the ideal central incisor position concerning incisal edge display at repose. A classic article by Vig and Brundo in 1978 outlined that a certain amount of tooth display shows below the lip line when a patient’s lips are relaxed and gently parted in repose. This amount of tooth display reduces as we age and lose elasticity in our upper lip.

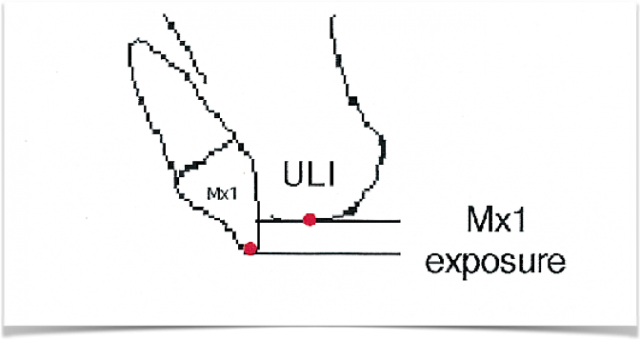

Vertical position

In his classic article on parameters of facial esthetics, Arnett2,3 further defined the ideal vertical position of the central incisor. He demonstrated that the center of the clinical crown in a patient with an unworn dentition should be positioned vertically at the wet/dry line of the upper lip when the lips are relaxed and parted.

Anterior/posterior position

Once the vertical position of the maxillary central incisor is determined, we must consider the anterior/posterior position of the tooth. A central incisor may be in the ideal vertical orientation but may be retrusive or protrusive relative to the patient’s skeletal base, leading to an unesthetic outcome. What skeletal and facial landmarks can we use to determine if the central incisors are too far back or too far forward relative to the face?

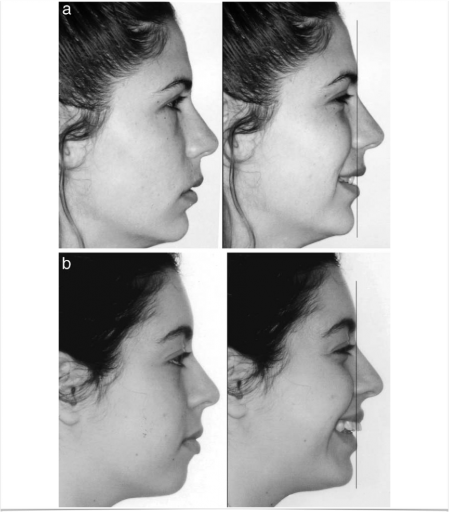

When we view our patients from a lateral perspective and the lips are together, we can often misdiagnose the anterior/posterior position of the central incisors. Therefore, Andrews et al.4 suggested the simple solution of examining our smiling patients from a lateral perspective. As you can see in the above photos from their paper, the diagnosis and treatment plan change when we can see the teeth relative to the smile.

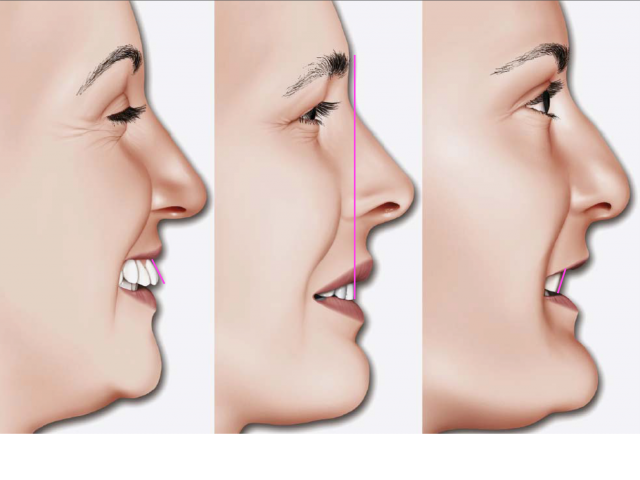

The forehead is a fixed skeletal landmark and is easy to identify in our patients. Drs. Larry and Will Andrews and Dr. Arnett have all identified the ideal anterior/posterior position of the central incisor relative to the skeletal base. They all independently identified that the ideal A/P position of the central incisor should be in approximately the same vertical plane as the forehead, or slightly back from the forehead. These concepts are illustrated in the following illustrations. As you can see, smile esthetics are compromised when teeth are proclined or retroclined relative to the forehead.

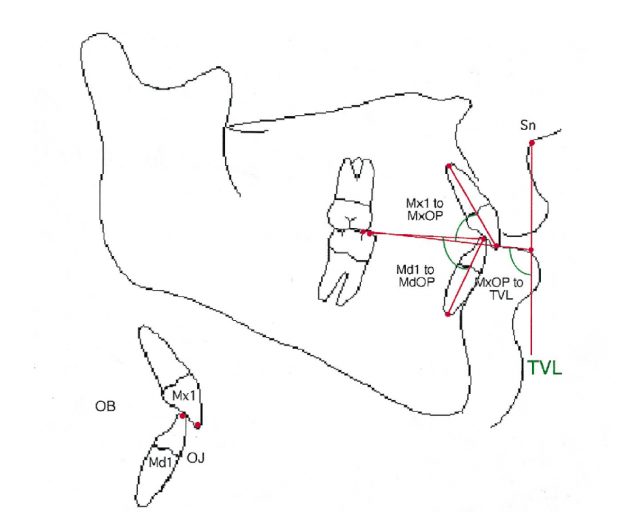

Angulation

An unfavorable angle of the maxillary central incisors can negatively influence esthetics. Proclined and retroclined incisors reflect light differently.5 Furthermore, retrusive maxillary incisor positions are significantly less desirable esthetically.6

The anterior/posterior position of the maxillary central incisor is critical to predicting airway health. In the absence of obesity, the odds of having moderate to severe sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) increase threefold to sevenfold when the central incisor (premaxilla) is retrusive.

The retrusive position of the maxilla decreases the horizontal cross-section of the posterior pharyngeal airway space. A constricted maxilla puts the patient at risk for pharyngeal wall collapse with loss of muscle tone. The ideal anterior/posterior position of the central incisor is critical for esthetics and airway health in our patients.

Upright or retrusive incisors contribute to excessive wear and can lead to a restricted envelope of occlusal function. Retrusive maxillary incisors restrict the movement of the mandible as they guide the arc of mandibular closure posteriorly. Additionally, as the mandible moves anteriorly, the lower incisors’ facial surfaces and incisal edges will run into the maxillary incisors’ palatal aspects, leading to enamel loss and dental destruction on these opposing surfaces. Creating the ideal interincisal angle allows for proper disclusion of both arches and protects the incisors from excessive wear.

What is the ideal incisor angle for function as well as esthetics? Dr. Arnett defined the ideal incisor angle as approximately 57° from the functional occlusal plane. This ideal angle allows for anterior guidance, does not restrict mandibular movement in a chewing cycle, and allows for proper phonetics and esthetics.

In summary, three-dimensional placement of the maxillary central incisor is critical to comprehensive treatment planning. Vertically, the center of the maxillary central incisor should fall at the same height as the wet/dry line of the upper lip when the lips are relaxed and gently parted. This allows for a youthful appearance.

In the anterior/posterior dimension, the center of the crown of the maxillary central incisor should be in the same vertical plane as the most prominent part of the forehead when the patient is in a natural head position. This allows for maximum esthetics and is key to airway health.

Finally, the root angulation of the central incisor is key to proper function and to preventing future wear. The maxillary central incisor should be angled at approximately 57° from the functional occlusal plane.

References

- Arnett GW, Jelic JS, Kim J, Cummings DR, Beress A, Worley Jr. CM, Bergman R. (1999). Soft tissue cephalometric analysis: Diagnosis and treatment planning of dentofacial deformity. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 116(3), 239–253.

- Arnett, GW, Bergman RT. (1993). Facial keys to orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning—Part I. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 103(4), 299–312.

- Arnett, GW, Bergman RT. (1993). Facial keys to orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning—Part II. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 103(5), 395–411.

- Andrews, WA. (2008). AP relationship of the maxillary central incisors to the forehead in adult white females. The Angle Orthodontist, 78(4), 662–669.

- Ciucchi P, Kiliaridis S. (2017). Incisor inclination and perceived tooth colour changes. European Journal of Orthodontics, 39(5), 554–559.

- Schlosser JB, Preston CB, Lampasso J. (2005). The effects of computer-aided anteroposterior maxillary incisor movement on ratings of facial attractiveness. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 127(1), 17–24.

VIRTUAL SEMINARS

The Campus CE Experience

– Online, Anywhere

Spear Virtual Seminars give you versatility to refine your clinical skills following the same lessons that you would at the Spear Campus in Scottsdale — but from anywhere, as a safe online alternative to large-attendance campus events. Ask an advisor how your practice can take advantage of this new CE option.

By: Rebecca Bockow

Date: November 11, 2017

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts