Treating TMD: Similarities Between Spear’s Occlusal Exam and the DC/TMD

Author’s note: This article is the second in a two-part series about how Spear’s clinical examination gathers all the information required for the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders guidelines used by orofacial pain specialists, and how those details affect the diagnosis and treatment of TMD cases.

To help readers compare the Spear exam and the DC/TMD, the series refers to 10 key points established in 2024 by the International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Methodology.

Part 1 of this series, which focused on the etiology and tentative diagnosis of TMD, highlighted Points 1–4. This article, which includes Points 5–10, concentrates on the additional diagnostic information needed to assist the patient in determining the appropriate treatment path, based on examination, diagnostic tests, and imaging.

Point 5: “Imaging has been proven to have utility in selected cases but does not replace the need for careful execution of history taking and clinical examination. Magnetic resonance imaging is the current standard of care for soft tissues and cone beam computerized tomography for bone. Imaging should only be performed when it has the potential to impact the diagnosis or treatment. Timing of imaging is important and so is the cost:benefit:risk balance.”

The Spear curriculum teaches that every new patient examination should begin with an evaluation. However, the completed assessment leads only to a tentative diagnosis — a preliminary suspicion based on the patient’s symptoms and the doctor’s experience and knowledge. In medicine, patients are generally advised to undergo further testing to confirm the diagnosis.

Orofacial pain specialists recognize that TMD is not a standalone diagnosis but may include one or more of the following: muscular issues, joint problems, headaches, and other conditions categorized as TMD, such as sympathetic hyperactivity. When muscle pain is identified as the primary source, operating under a tentative diagnosis is acceptable; however, myalgia is often secondary to a TM joint condition or sympathetic hyperactivity resulting from poor sleep quality.

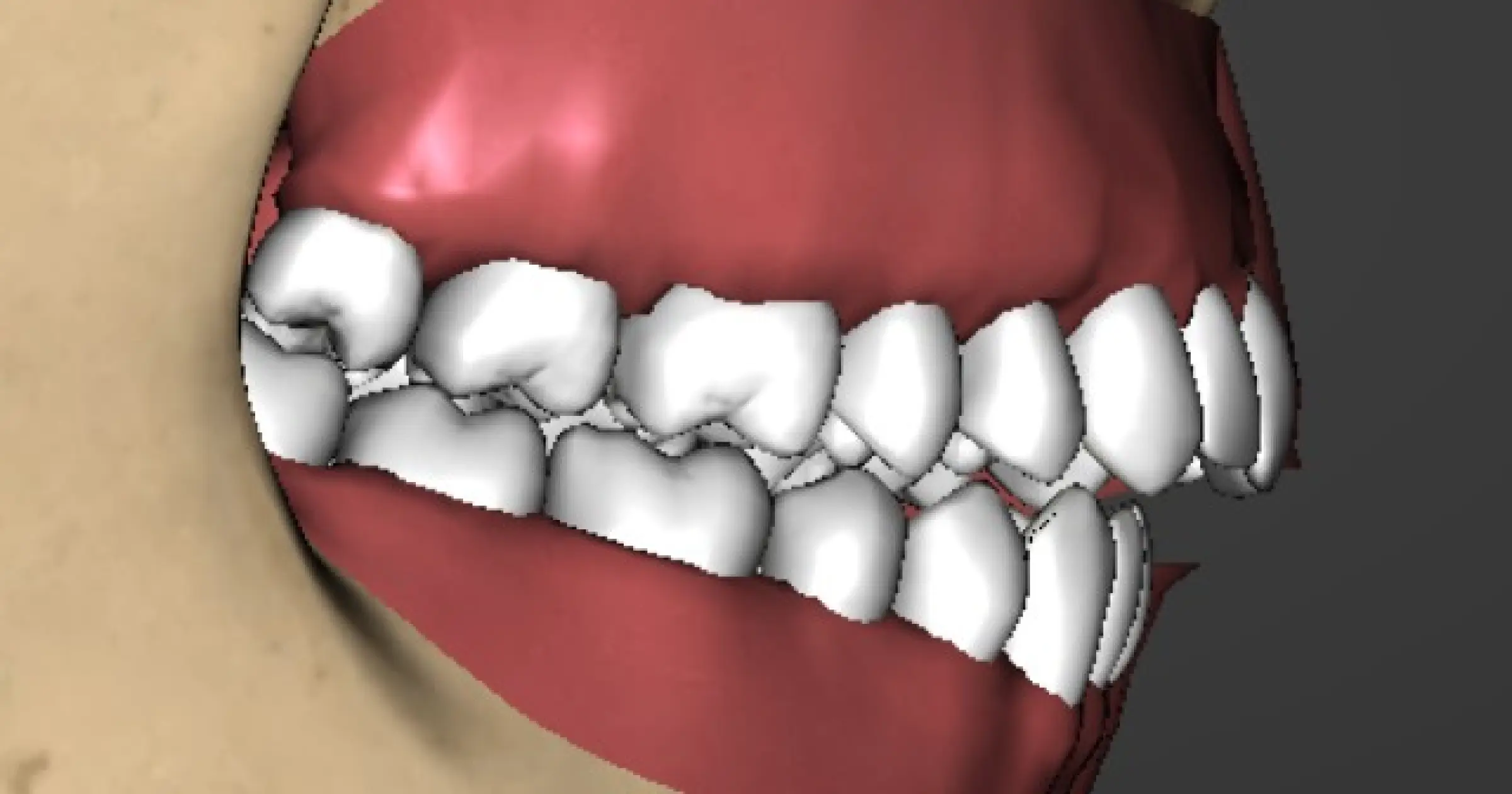

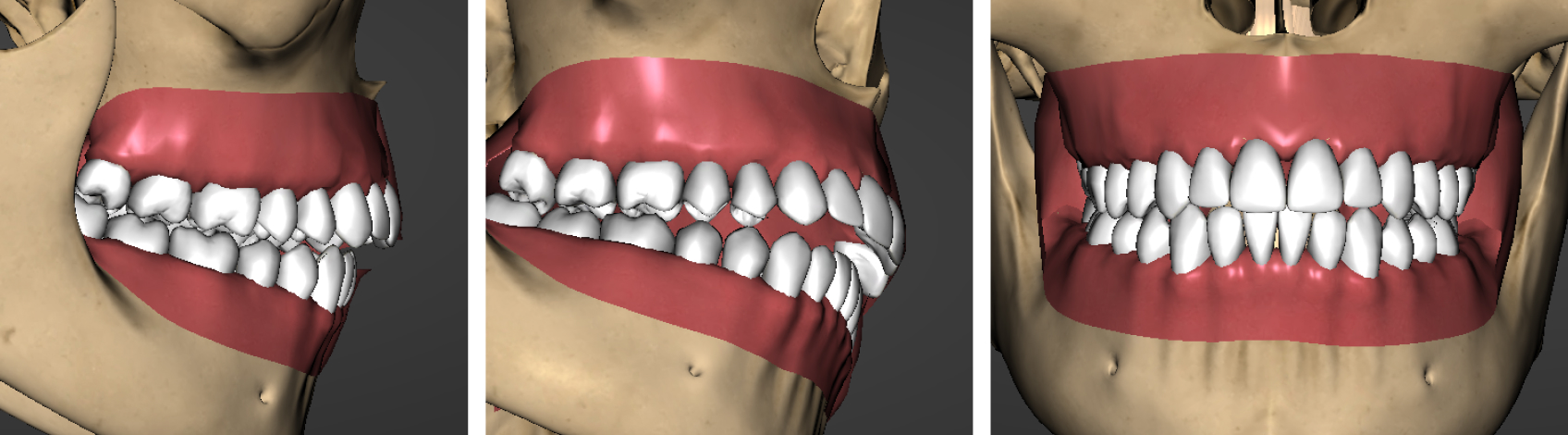

The occlusal examination taught during Spear workshops emphasizes “reading the bite” to screen for underlying TMJ conditions that can lead to myalgia. This concept assesses the relationship of the anterior teeth with the condyles in the fully seated position, or centric relation. Patients with an overjet, open bite, or discrepancy between the maxillary and mandibular midlines of 2 mm or more (Figures 1a–c and Figures 2a–c) face an increased risk of changes in the temporomandibular joints.

If there are concerns regarding the stability of the temporomandibular joints before restorative treatment, imaging is essential because changes in the joints can affect occlusal stability. A CBCT and MRI provide valuable insights into the health of the osseous structures and the position and condition of the disk, which may affect the stability of the restorative treatment.

Point 6: “The evidence base for all interventions or devices should be carefully considered before their implementation over and above normal standard of care. Knowledge on developments in the field should be kept up to date. Currently, technological devices to measure electromyographic activity at chairside, to track jaw motion, or to assess body sway, amongst others, are not supported.”

The devices mentioned above can serve as an adjunct to support forming a tentative diagnosis. One tool I use with patients suffering from TMD is a cardiopulmonary coupling unit, which measures the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity during sleep. Sympathetic hyperactivity can lead to muscle dystonia and soreness. The CPC helps assess risks and identify the areas that need attention to relieve the soreness.

Point 7: “TMD treatment should aim to reduce the impact of pain and decrease functional limitation. Outcomes should be evaluated also in relation with the reduction of exacerbations, education in how to manage exacerbations, and improvement in quality of life.”

Point 8: “TMD treatment should primarily be based on encouraging supported self-management and conservative approaches, such as cognitive–behavioral treatments and physiotherapy. Second-line treatment to support self-management includes provisional, interim, and time-limited use of oral appliances. Only very infrequently, and in very selected cases, are surgical interventions indicated.”

TMD can manifest as pain or changes in the occlusal relationship. When pain prompts an individual to seek treatment, a conservative approach, which typically involves identifying the activities that contribute to TMD discomfort, is advisable. For example, if overuse leads to muscle or joint soreness, a soft diet can help determine whether the condition is a reversible acute one or necessitates more complex treatment.

If self-management and conservative methods fail, the patient may pursue a more thorough evaluation. This includes patients with ongoing pain or concerns about alterations in their bite. Behavioral modification does not tackle these issues.

Two common causes of occlusal changes are growth disturbances and structural alterations in the TM joints. Occlusal changes may indicate that active processes are occurring in the temporomandibular joints. Imaging with CBCT and MRI helps the dentist present treatment options. A high-risk patient may be an adult with a medially displaced disk, marrow edema, and an incomplete cortical plate formation.

Treatment options for these patients range from no intervention to surgical procedures. In the Advanced Occlusion workshop at Spear, these options, along with the benefits and risks of each, are discussed. Neglecting treatment can lead to further joint degeneration and occlusal instability.

Splint therapy can effectively manage joint conditions and evaluate occlusal stability. The aim is to relieve pressure on the joints, allowing them to adapt. Furthermore, the splint provides valuable insight into the stability of the occlusion, which is essential before starting any restorative dental work.

The final option to discuss is surgical intervention. While it’s generally accepted this should be the last resort, certain circumstances may warrant a disk repair, replacement, or total joint surgery as the only viable solution to address the patient’s presenting conditions, whether they involve pain or occlusal changes.

Point 9: “Irreversible restorative treatment or adjustments to the occlusion or condylar position are not indicated in management of the majority of TMDs. The exception to this may be an acute change in the occlusion, such as in the instance of a high filling or crown with TMD-like symptoms developing immediately following these procedures or a slowly progressing change in dental occlusion due to condylar diseases.”

Irreversible restorative treatment is seldom recommended for temporomandibular joint disorders before attempting a conservative approach. However, when restorative treatment is necessary, verifying stability is crucial to ensure the long-term success of the restorations. A loss of vertical dimension in the TM joints will lead to a Class 2 occlusal shift, resulting in prematurity among the most distal teeth. If there is active breakdown in the TM joints, it may be essential to consider surgical options to maintain occlusal stability.

Another reason to start with more advanced diagnostics is that it could help identify a growth disturbance. Early intervention can encourage growth and prevent the need for more aggressive procedures such as maxillomandibular advancement surgery.

A herniation of the articular disk can interfere with growth in the condylar head, leading to a Class 2 mandibular shift. Early recognition and diagnosis using CBCT and MRI are essential for predicting future growth. A patient with disk displacement without reduction has a lower likelihood of growth than one with anterior disk displacement with reduction. The reduction must be in the functional appliance’s treatment position (typically the Class 1 canine position).

A diagnosis using a CBCT and MRI also identifies the adolescent patient with anterior disk displacement without reduction. Early surgical intervention to correct the disk position will help maintain the viability of the growth center in the condyle and may help avoid more aggressive procedures, such as temporomandibular joint replacement or maxillomandibular advancement.

Point 10: “The presence of complex clinical presentations with uncertain prognosis, such as in the case of concurrent widespread pain or comorbidities, elements of central sensitization, long-lasting pain, or history of previous failed interventions, should lead to the suspicion of chronification of TMDs or non-TMD pain. Referral to an appropriate specialist is thus recommended; the specialty will be geographic-specific as not all countries have a specialty of orofacial pain.”

As noted in the DC/TMD, pain in the temporomandibular joint can arise from several sources, including the TM joint itself, the cervical spine, and sympathetic dysfunction. TM joint pain can be muscular but may also stem from outside sources, including a herniated disk embedded in a muscle, a disk compressing a nerve, or a disk displacing the condyle, stretching ligaments. Additionally, edematous bone may become painful because of repetitive trauma to the condylar head.

The cervical spine can be a source of referred pain that mimics discomfort in the TM joint. While it is beyond the scope of this article, physical therapy and chiropractic care are often used in conjunction with TMJ treatment.

Finally, sympathetic hyperactivity that may result from complex regional pain syndrome, stress, pain, or poor sleep quality should be addressed to manage pain and occlusal instability effectively. Increased sympathetic tone can worsen muscle dystonia and decrease pain thresholds in people who don’t experience deep or restful sleep and thus miss the benefits provided by the parasympathetic nervous system.

In conclusion, the DC/TMD and Spear examination processes are well aligned. The examination methods taught in the Spear workshops meet the standard of care established by the orofacial pain specialty. In addition to diagnosing the source of pain, the Spear examinations also assist in diagnosing, managing, and treating occlusal instability.

SPEAR NAVIGATOR

Transform how your practice runs by engaging the team through

coaching and training

A guided path to excellence through structured coaching and self-guided resources that will align your team, streamline processes and drive growth. Transform your practice by implementing Spear’s proven playbooks for developing and retaining a high-performing dental team.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

SPEAR ONLINE

Team Training to Empower Every Role

Spear Online encourages team alignment with role-specific CE video lessons and other resources that enable office managers, assistants and everyone in your practice to understand how they contribute to better patient care.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

VIRTUAL SEMINARS

The Campus CE Experience

– Online, Anywhere

Spear Virtual Seminars give you versatility to refine your clinical skills following the same lessons that you would at the Spear Campus in Scottsdale — but from anywhere, as a safe online alternative to large-attendance campus events. Ask an advisor how your practice can take advantage of this new CE option.

FOUNDATIONS MEMBERSHIP

New Dentist?

This Program Is Just for You!

Spear’s Foundations membership is specifically for dentists in their first 0–5 years of practice. For less than you charge for one crown, get a full year of training that applies to your daily work, including guidance from trusted faculty and support from a community of peers — all for only $599 a year.

By: Curt Ringhofer

Date: June 3, 2025

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts