Spear Digest

Learn From Our Blog Articles and Case Studies

Learn from Spear Faculty and partners through articles on occlusion, restorative dentistry, dental implants, esthetics, and more — insights that help you refine your skills and grow your practice.

Sort By

No results found.

-

- Treatment Planning

Comprehensive Dental Treatment Planning Starts With the Patient

Comprehensive dental treatment planning starts with understanding the person. Learn how better questions lead to care patients accept.By Ricardo Mitrani

• January 13, 2026

-

- Finance

Start 2026 Strong: 4 Financial Moves to Make Now

Take control of your financial future with practical steps every dentist can use to improve cash flow, build personal wealth,…By Angie Svitak

• January 6, 2026

-

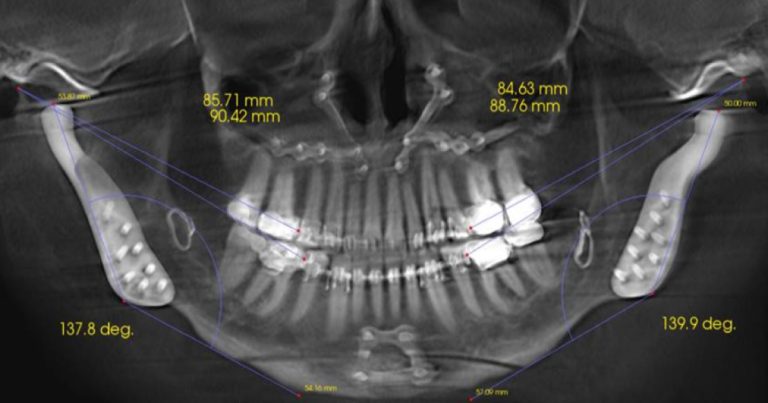

- Occlusion / Wear

Why Do Jaws Hurt? Rethinking Orofacial Pain in the 3D Imaging Era

Modern 3D imaging has upended the old belief that jaw pain is just stressed muscles, revealing a host of joint,…By Jim McKee

• December 30, 2025

-

- Techniques / Materials

Bonding Systems and Adhesive Strategy, Part 3

In the third installment of a series about bonding and adhesives, Dr. Jason Smithson compares etch-and-rinse and self-etch bonding strategies…By Jason Smithson

• December 16, 2025

-

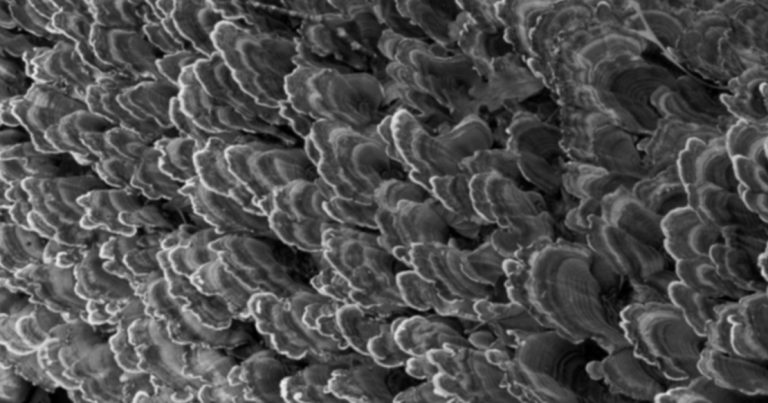

- Techniques / Materials

Bonding Systems and Adhesive Strategy: Current State of the Art

In the second installment of a series about bonding and adhesives, Dr. Jason Smithson explains strategies of bonding to enamel,…By Jason Smithson

• December 2, 2025

-

- Techniques / Materials

Bonding to Enamel and Dentin: A Dichotomy of Substrates

In the first installment of a series about bonding and adhesives, Dr. Jason Smithson explains the challenges of bonding to…By Jason Smithson

• November 18, 2025

-

- Occlusion / Wear

Occlusal Stability: When Is It Safe To Treat?

A restorative treatment plan aims to design a stable occlusion to protect the restorations. However, understanding “when it’s safe to…By Curt Ringhofer

• November 6, 2025

-

- Practice Management

Leading With Abundance: Unlocking the Power of FLOW To Build Winning Teams

For a team to truly thrive, leaders must create an environment of engagement, fulfillment, and focus. Spear Resident Faculty member…By Ricardo Mitrani

• October 21, 2025

Your Journey to Great Dentistry

Starts Here!

Opt in to receive our biweekly newsletter spotlighting the latest articles, events, seminars, workshops, courses, free downloads, and more from Spear.