Mouth Rinsing With Bleach: A Promising Alternative to Chlorhexidine?

Mary, 74, comes to the office every three months, like clockwork, for her cleanings. And every three months, her teeth are covered in plaque. We use hand mirrors and demonstrate the brushing technique. We discuss improving her dietary choices and managing her dry mouth with sugar-free mints and lozenges. We stress the importance of her oral hygiene in preserving the abutment teeth for her partial denture.

And, oh, did I mention Mary only has four teeth?

We all have patients who, whether due to issues with dexterity, diet, or medication-induced xerostomia, are constantly fighting a battle with plaque buildup and bleeding gums. Mary falls into all three categories, and despite her best efforts to maintain what’s left of her dentition, she’s gradually losing the battle.

Mary has used chlorhexidine mouth rinses before, but because of cost, tooth staining, and the effects on her sense of taste, it has been more of an on-and-off routine. I resigned myself to the fact that there wasn’t much more I could do or recommend.

However, this year, I started hearing about mouth rinsing with dilute sodium hypochlorite as an effective way of reducing dental plaque levels, and the idea piqued my curiosity enough to make me look more into the history and literature behind its use.

How can bleach reduce dental plaque levels?

Sodium hypochlorite, one of the main active ingredients in household bleach, has been used as an antibacterial agent since the mid-19th century, when doctors used to wash their hands with it and noticed dramatically reduced disease transmission between patients. However, it wasn’t until 1920 that the first published use of sodium hypochlorite was documented in endodontic root canal therapy.

As a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent, sodium hypochlorite has long been studied on the anaerobic bacteria that cause endodontic infections, but in vitro studies done with 0.5% sodium hypochlorite solutions have shown it to also be effective against S. mutans, S. sanguinis and Lactobacillus acidophilus, all bacteria that can routinely be found in the oral environment.

Concentrated sodium hypochlorite can be extremely caustic and cause extremely damaging tissue destruction. But as most backpackers can tell you, bleach can treat potentially contaminated water sources and still be safe to drink when properly diluted. New studies are being done that show that using highly diluted household bleach as a mouth rinse can cause a significant reduction in dental plaque formation and bleeding on probing sites without some of the side effects of long-term chlorhexidine use.

A randomized control trial that compared the effects of swishing twice a week with 0.25% sodium hypochlorite (versus water), in addition to a person’s oral hygiene routine, showed statistically significant improvements in plaque-free surfaces and the number of sites with bleeding on probing after three months. The only reported side effects had to do with the taste of the rinse itself.

Another study measured the effects of a 0.05% Clorox rinse instead of brushing. The control group, which only swished with water, had statistically significantly higher plaque-index scores, higher levels of gingival inflammation as measured by the Loe and Silness Index, and more bleeding on probing sites. The latter study seems to benefit patients who may not have the dexterity to break up the plaque biofilm properly via mechanical means.

This all sounded promising, but I could just imagine the blank stares I was about to receive from any patients to whom I recommended swishing with bleach. Patients seem to be all about any home remedy they can find — until their doctor recommends it. I remember getting similar reactions when I advised my mouth-breathers to try taping their lips shut before going to bed. Same as then, I knew if I wanted to get any semblance of compliance, I had to try it out myself.

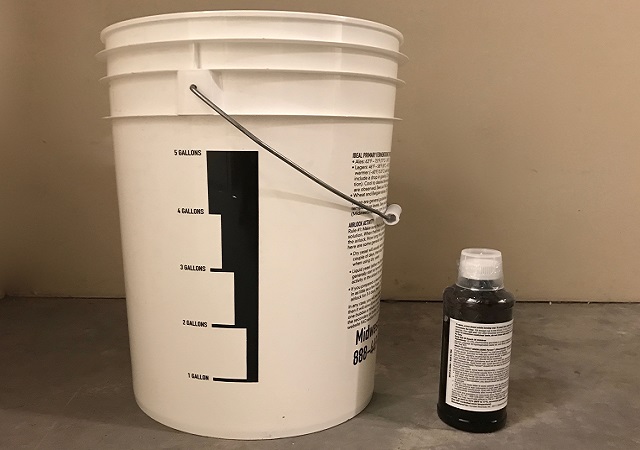

How to dilute bleach for patient use

As mentioned before, household bleach is extremely caustic and dangerous, and needs to be properly diluted to be handled safely. Standard bleach is 6% sodium hypochlorite; the two studies I cited above were performed with 0.25% and 0.05% solutions. This means we would need to dilute it by a factor of at least 24.

I don’t know about your patients, but this isn’t simple mental math for me. I’ve worked the conversions out so that if you add 2 teaspoons of bleach to 1 cup of water, you’ll have yourself a roughly 0.26% solution.

Words of warning: Make sure you’re using unscented, fragrance-free formulations and making each batch as fresh as possible. Also, please double-check the percentage of the sodium hypochlorite on your bottle; some “concentrated” versions contain more than 8%.

As I mixed my first batch, my nostrils began to flare and my eyes started to water. I instantly began to doubt myself. I double-checked my math. I triple-checked, to make sure I didn’t miss a zero. I couldn’t help feel like I was about to take a big sip of hot tub water. I set my timer for 30 seconds and began to swish.

Toward the end, I could feel a slight tingly sensation from the bubble formation, though nothing painful. The taste, however, was pretty awful — there’s no way to sugarcoat it. I knew that I was unlikely to be able to convince anyone to willingly incorporate this into their routine. Later that day, after my taste buds had fully recovered, I decided to try it again, diluting my previous ratio in half, using 1 teaspoon per cup of water.

I was pleasantly surprised by how big of a difference that extra dilution made. Theoretically, at 0.13% sodium hypochlorite, I was still within the potentially effective range, and found the taste of bleach only barely detectable. A glimmer of hope!

While I don’t plan on implementing or recommending this regimen to all my patients right away, I would keep it in my back pocket as a low-cost, twice-weekly option for patients who cannot seem to improve their plaque levels despite their earnest efforts. I look forward to seeing larger, long-term studies being done evaluating its efficacy and any potential adverse reactions or unintended consequences that may arise after prolonged use.

References

- De Nardo R, Chiappe V, Gómez M, Romanelli H, Slots J. (2012). Effects of 0.05% sodium hypochlorite oral rinse on supragingival biofilm and gingival inflammation. International Dental Journal, 62(4), 208–212.

- Spencer HR, Ike V, Brennan PA. (2007). The use of sodium hypochlorite in endodontics—potential complications and their management. British Dental ournal, 202(9), 555–559.

- Crane AB. (1920). A Practicable Root-Canal Technic. Lea & Febiger.

- Evans A, Leishman SJ, Walsh LJ, Seow, WK. (2015). Inhibitory effects of antiseptic mouthrinses on Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Australian Dental Journal, 60(2), 247–254.

- Galván M, Gonzalez S, Cohen CL, Alonaizan FA, Chen CTL, Rich SK, Slots J. (2014). Periodontal effects of 0.25% sodium hypochlorite twice‐weekly oral rinse. A pilot study. Journal of Periodontal Research, 49(6), 696–702.

FOUNDATIONS MEMBERSHIP

New Dentist?

This Program Is Just for You!

Spear’s Foundations membership is specifically for dentists in their first 0–5 years of practice. For less than you charge for one crown, get a full year of training that applies to your daily work, including guidance from trusted faculty and support from a community of peers — all for only $599 a year.

By: Imahn Moin

Date: November 1, 2017

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts