Occlusal Stability: When Is It Safe To Treat?

A restorative treatment plan aims to design a stable occlusion to protect the restorations. However, understanding “when it’s safe to treat” can be complicated. The dentist and the patient must understand the risks before treatment, and when the patient understands the risks beforehand, they can make an informed decision.

If the dentist fails to recognize the risks and the restorative work fails, the patient may perceive the failure as poor dental work when the actual reason for the failure often is the instability that may have contributed to the breakdown of the existing dentition. Therefore, it’s imperative to ensure the occlusion is stable before treatment begins.

Evaluating stability starts by understanding the design of the occlusal system. Historically, dentistry believed that malocclusion was the root of parafunction, muscle soreness, and TMD, with the notion that “bad bites cause bad joints.” However, a growth disturbance in the maxillary or mandibular skeleton may also contribute to malocclusion. Form inevitably follows function, and a disturbance in craniofacial growth often leads to malocclusion, affecting both the static and dynamic occlusion.

The occlusal system and growth

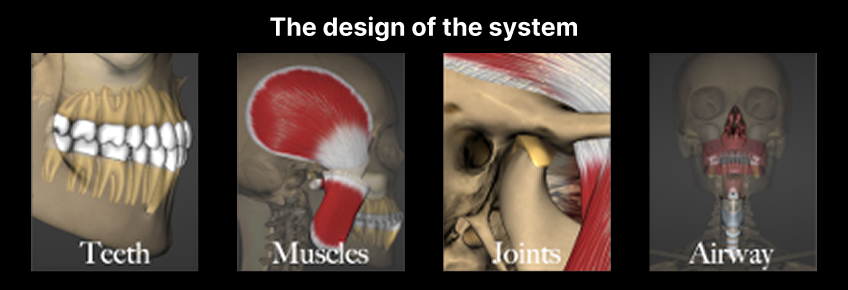

The “design of the occlusal system” includes the teeth, muscles, temporomandibular joints, and airway (Fig. 1). Proper occlusion depends on all four areas working in harmony. Understanding growth provides insight into why malocclusion develops and how early intervention can provide a platform for a stable occlusion.

The three main areas of craniofacial growth are the maxillary suture system, the dentoalveolus, and the condyle of the mandible. In normal growth and development, a significant portion of maxillary growth occurs within the first five postnatal years, and the anterior dentoalveolar height closely approaches its adult size by age five.

Airway-disordered breathing often originates from a lack of nasal breathing. Although it’s beyond the scope of this article, the inhibition of nasal breathing results in oral breathing and an open-mouth posture. A “mouth breather” rests their tongue on the floor of the mouth, away from the palate, restricting its influence on the growth of the maxilla. A tongue that rests on the palate contributes to widening the palate and advancing the pre-maxilla by counteracting the forces from the facial muscles. Patients with a dolichocephalic profile (Fig. 2) often have a history of airway-disordered breathing.

Growth of the condyle is the primary influence on mandibular development; bone apposition in the condylar cartilage results in the forward development of the mandible. Studies have shown a disruption of vertical growth of the condyle when there’s a disk displacement in adolescent patients, perhaps caused by a chronically displaced disk altering the normal functional environment.

The disk is responsible for load distribution and, under compression, secretes synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and provides nutrition to the articular cartilage of the condyle. In a structurally altered temporomandibular joint, damage can occur to tissues because of the compressive and shear forces of the condyle under normal function. In growing patients, this may lead to a premature closure of the growth center, inhibiting the anterior projection of the mandible.

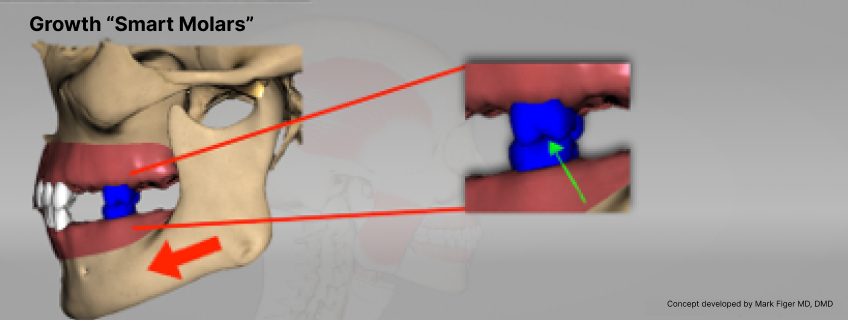

Normal growth depends on a symbiotic relationship between the maxillary and mandibular arches. As the maxillary arch develops, condylar growth is stimulated by the interaction of the mandibular teeth with the maxillary teeth. Dr. Mark Piper described the adult first molars as the “smart molars,” emphasizing that the interaction between the maxillary and mandibular molars stimulates growth. When the mesial inclines of the maxillary molars contact the distal inclines of the mandibular molars, it pulls the condyle out of the fossa, inducing growth — a process similar to distraction osteogenesis (Fig. 3).

However, a growth disturbance in either the maxilla or mandible may result in malocclusion and instability in the system.

Identifying patients with occlusal instability

Class I patients are typically the easiest to treat, because the skeleton and dentition are properly positioned. The risk of instability increases when the skeleton and dentition are in the wrong position. A deficient maxilla associated with normal mandibular growth will lead to a Class III skeletal–dental relationship, which can pose esthetic concerns.

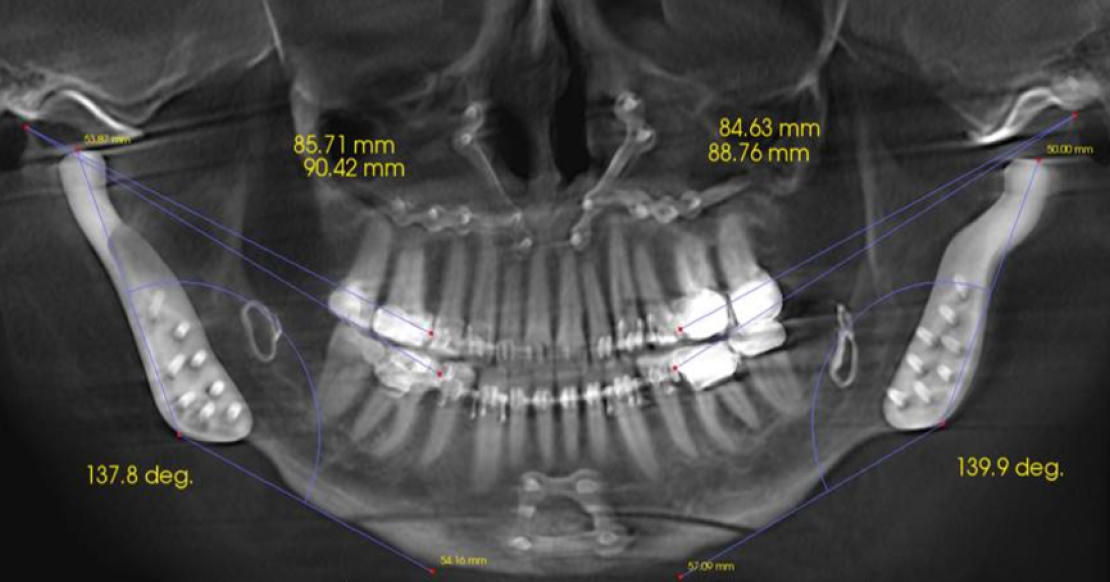

Patients presenting with a Class II occlusion can also be challenging to restore, because of the lack of anterior tooth contact. Depending on the extent of the Class II relationship, these plans require more extensive intervention; they may necessitate orthodontic treatment, orthognathic surgery, or both (Fig. 4) to correct the skeletal relationship before predictable restorative treatment can begin.

Early recognition and intervention are ideal to ensure adequate growth. The window to stimulate growth has often been missed in the adult population, so restorative, orthodontic, or orthognathic interventions may be needed to correct the occlusion and

esthetics. Stability in the system is imperative for the long-term success of the treatment.

Historically, pain was used to recognize instability, but skeletal and dental malocclusion, with or without pain, needs to be evaluated before treatment.

When pain is associated with a structurally altered TM joint, symptom relief becomes a primary reason to treat. However, for the restorative dentist, it’s essential to recognize the stability in the TM joint foundation. Historically, the diagnosis of TM joints has been based on a “tentative diagnosis” from clinical examination findings, but an accurate diagnosis depends on using advanced imaging techniques to evaluate the hard and soft tissues.

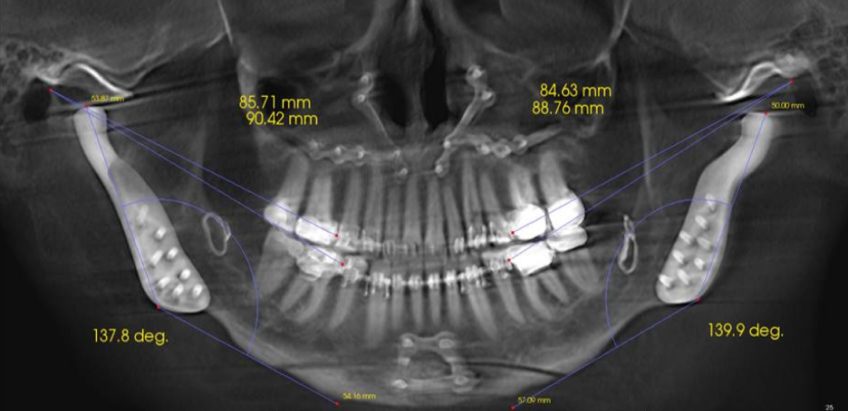

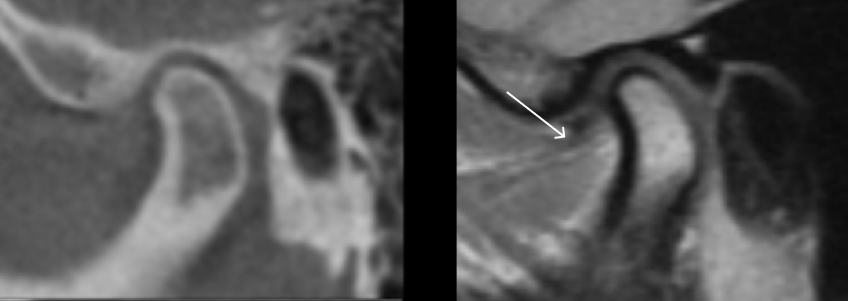

A CBCT provides a noninvasive means to diagnose osseous pathology and an MRI is used to assess the position and condition of the articular disk. However, the cost and availability of MRIs can remain obstacles to obtaining this imaging.

The prevalence of TMD in the general population can be as high as 75% and occur at any age. As previously mentioned, treatment has been centered on symptom relief, but the key to patient management is whether the articular disk is stable. Dr. Piper said, “Both the dentist and their patients must understand that the ultimate foundation for the dental occlusion is the temporomandibular joint itself, and it is this foundation that ultimately will determine whether occlusal management will remain predictable and stable.” Instability in the temporomandibular joints can lead to unsatisfactory treatment outcomes relative to function, esthetics, stability, and pain.

Understanding the condition of the osseous structures and the position of the articular disk is critical to diagnosing the temporomandibular joints. Considering that the TM joint is one of the most complicated joints in the body, it’s important to understand anatomy before treatment by using advanced imaging techniques. The MRI is considered the gold standard for diagnosing the condition and position of the articular disk.

A CBCT can serve as a screening tool by assessing the joint space and cortical plate in sagittal, coronal, and axial views. The normal thickness of the disk is typically 2–3 mm, and as Dr. Jim McKee describes in Spear’s Advanced Occlusion workshop, it acts as a gasket in the temporomandibular joint. If the articular disk herniates, it can lead to a “wobble” and instability in the system.

Assessing and evaluating the TM joint

A cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is considered the best method for assessing the osseous structures of the TM joints. However, evaluating the joint space can be a useful way to screen for disk displacement. An increased anterior joint space and a decreased posterior and superior joint space can indicate an anterior disk herniation.

A study by Yu that used both MRI and CBCT images showed that out of 52 joints that presented with larger-than-normal anterior joint spaces and reduced posterior and superior joint spaces, 45 (87%) had disk displacements. A disk displacement changes the position of the condyle in the fossa, and an altered position of the condyle is dependent on the extent and direction of the disk displacement.

The same study revealed that healthy joints’ posterior–anterior (P-A) and superior–anterior (S-A) ratios had the condyles in a centric position, with a 1.6 and 1.9 ratio, respectively. In the disk displacement group, the joints showed a significant decrease in the P-A and S-A ratios because of an enlarged anterior joint space.

However, caution must be taken if one uses a CBCT alone to diagnose the disk position. The dentist can be fooled when the disk is degenerated and anteriorly displaced if the retrodiscal tissue assumes a similar dimension as the healthy disk (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, understanding the anatomy of the temporomandibular joints before starting treatment in both adolescent and adult patients is imperative for a positive treatment outcome. Because disk displacements are frequently found in asymptomatic patients, including pre-orthodontic patients, CBCT and MR imaging is necessary for those exhibiting signs of decreased growth in the maxillary and/or mandibular arches.

The MRI provides superior images in multiple condylar positions without radiation exposure, but availability can be an obstacle. Therefore, a CBCT can be used as a screening tool through joint space evaluation. While an increased anterior joint space can indicate an anterior disk displacement, an MRI is necessary to diagnose the temporomandibular joints accurately.

References

- Flores-Mir C, Nebbe B, Heo G, Major PW. Longitudinal study of temporomandibular joint disk status and craniofacial growth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006 Sep; 130(3):324–30.

- Nebbe B, Major PW, Prasad NG, Grace M, Kamelchuk LS. TMJ internal derangement and adolescent craniofacial morphology: A pilot study. Angle Orthod. 1997; 67(6):407–14.

- Morais-Almeida M, Wandalsen GF, Solé D. Growth and mouth breathers. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019 Mar–Apr; 95 Suppl 1:66–71.

- Yu W, Jeon HH, Kim S, Dayo A, Mupparapu M, Boucher NS. Correlation between TMJ space alteration and disc displacement: A retrospective CBCT and MRI study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Dec 25; 14(1):44.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Curt Ringhofer

Date: November 6, 2025

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts