Temporomandibular Joint Space and Articular Disk Position: Is There a Correlation?

The temporomandibular joint is a complex diarthrodial joint, one of the most intricate in the human body. More specifically, it’s classified as a ginglymoarthrodial joint, meaning it allows both hinge and gliding movements (Fig. 1). The TM joint must withstand high mechanical stress during function and, unlike other joints, remains under constant load even at rest.

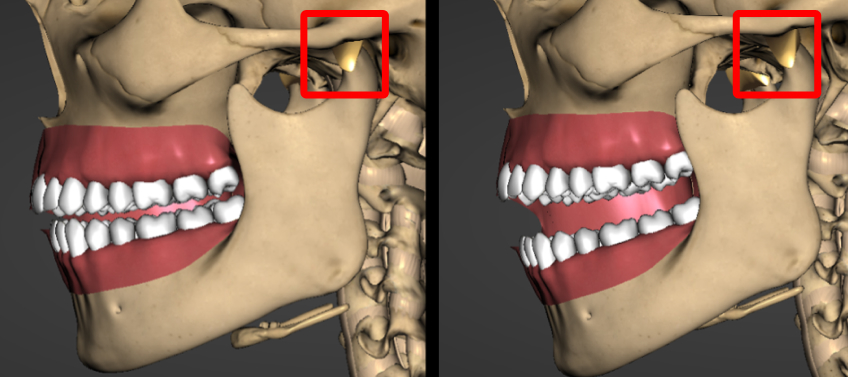

The articular disk helps distribute the load and protect the articular cartilage. Under compression, the disk secretes synovial fluid that lubricates the joint and supplies nutrients to the cartilage. An anterior herniation of the articular disk can lead to degeneration of the cartilage, creating a hypoxic–reoxygenation cycle due to increased pressure on the condyle. In adolescents, this may cause premature closure of the mandibular condyle’s growth center (Fig. 2) or degenerative changes in the bony structures of adults.

The DC/TMD examination, the recognized standard of care for assessing the temporomandibular joints, emphasizes pain and how alleviating pain leads to stability. Although pain is often the main reason patients seek treatment for temporomandibular joint disorders, changes in the TM joints can occur before pain appears. (In Spear’s Advanced Occlusion workshop, Dr. Jim McKee says, “Signs will often precede symptoms.”) Early detection of occlusal changes caused by inadequate growth can help lower the risk of pain.

TMD is 3.5 times more common in female patients than males, and usually occurs between ages 20 and 40. However, identifying changes in the temporomandibular joints early can decrease the likelihood of TM joint pain and skeletal growth issues. The frequency of disk displacement is often underestimated, and while studies show that up to 30% of asymptomatic patients have a disk displacement confirmed by MRI, I believe this percentage is much higher in the Class II patient population.

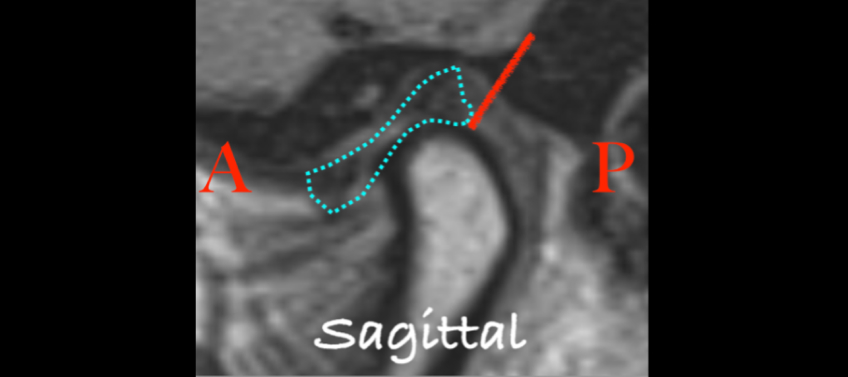

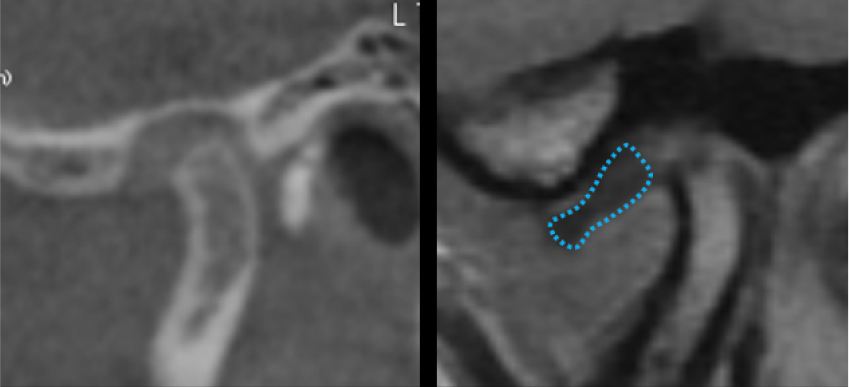

A Class II mandibular shift in a growing patient may indicate a structural change in the TM joints. The normal anatomy places the articular disk on top of the condyle, with the posterior band at the 1 o’clock position (Fig. 3). When the disk is displaced anteriorly, the risk of early cessation of vertical condylar growth increases. Recognizing signs of temporomandibular joint changes helps both dentist and patient understand the risks of damage to the dentition or restorations caused by the Class II mandibular shift. A loss of vertical dimension in the TM joints often causes the first contact point to shift to the most distal teeth.

Dr. Mark Piper described the temporomandibular joint as the foundation of the occlusal masticatory system. Instability in this foundation affects both static and dynamic occlusion, so starting restorative treatment without ensuring the stability of the entire occlusal masticatory system — which includes dental occlusion, muscle coordination, TM joint health, and a stable airway — is like building a house on a weak foundation: It increases the risk of restorative failure.

Evaluating osseous structures

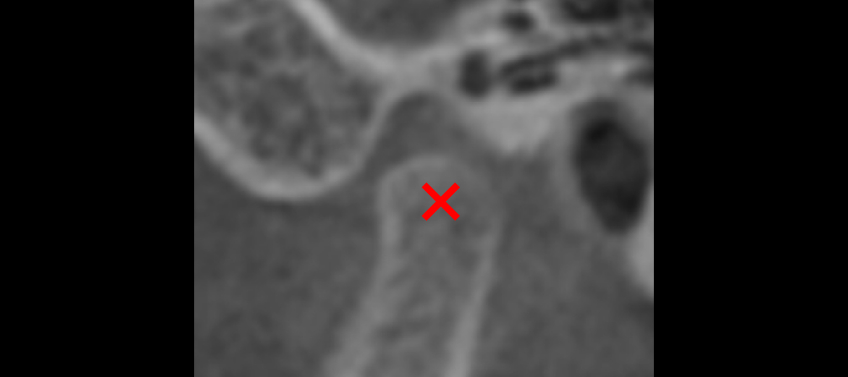

As previously mentioned, disk displacement can cause degenerative changes or hinder normal growth. Magnetic resonance imaging is the standard of care for assessing the position and condition of the disk and for detecting early signs of TM joint dysfunction; however, MRI availability can be limited. Cone-beam computed tomography has become more accessible in dentistry and can act as a guide for TMJ stability.

CBCT is ideal for evaluating osseous structures. The size and shape of the condyle and the intraarticular space can be assessed in conjunction with a comprehensive TM joint examination, providing insight into the position of the articular disk. In both adults and growing individuals, the condyle should take up about 66% of the glenoid fossa. If the condyle is not proportionate to the glenoid fossa, it may indicate an early growth disturbance, condylar breakdown, or a combination of both.

In addition to the size of the condyle, a normal shape of the condyle indicates protection for the articular disk, signifying that the articular cartilage is safeguarded. However, when there’s a disruption of the articular cartilage or the growth center, it results in a loss of vertical dimension in the mandibular condyle, leading to shorter ramus lengths.

“The temporomandibular joint is the foundation of the occlusal masticatory system, so starting restorative treatment without ensuring the stability of that system is like building a house on a weak foundation.”

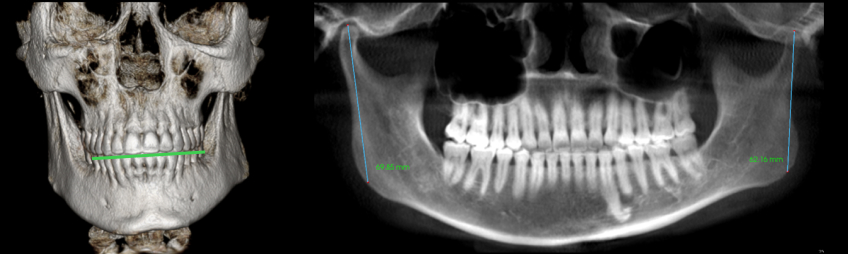

The height from the top of the condyle to the angle of the ramus (gonion) in adult patients is 60–70 mm. For a 5-year-old patient, the expected height is 40 mm, with 2–3 mm of growth annually. An adult patient with values below these ranges suggests arrested development. In growing patients, measurements below average indicate herniation of the articular disk.”

While the size and shape of the condyle indicate whether there was a growth disturbance or osseous breakdown, the space around the condyle in the glenoid fossa can serve as a screening tool to help determine if magnetic resonance imaging is necessary. A disk displacement can shift the condyle within the fossa, leading to changes in the space.

The articular disk is a biconcave structure that’s thicker on the anterior and posterior aspects, with a thinner avascular central bearing zone. The central bearing zone is typically 2–3 mm thick and functions to distribute the load between the condyle and the glenoid fossa. When the disk is properly positioned, the posterior band wraps around the back side of the condyle, positioning it in a concentric location (Fig. 4a). When a disk herniates, it can cause a deflection of the condyle, disrupting the joint space and providing insight into the disk’s position (Fig. 4b).

Dr. McKee explains that the disk acts like a gasket to stabilize the condyle within the fossa. When the joint space changes, the probability of disk displacement increases, which can cause instability in both growing and nongrowing patients. Such instability in the temporomandibular joints can influence treatment results and negatively affect aesthetics, function, and structure.

Esthetics can be affected by disruptions in growth or loss of dimension caused by arthritic changes in the TM joints.

- When the loss of vertical dimension is bilateral, it results in a Class II mandibular shift and a retrognathic profile.

- If the loss of vertical dimension is unilateral, it also causes a Class II shift and may affect the horizontal occlusal plane.

Differences in condylar heights often influence the maxillary arch, leading to an occlusal cant or a stepped occlusal plane (Fig. 5).

A Class II occlusal relationship often causes an excessive overjet, making it difficult to establish anterior guidance and resulting in excessive wear on posterior teeth. When the maxillary and mandibular teeth are assessed in the fully seated condylar position, the first point of contact is usually on the second molars or the most distal teeth. If a patient functions in the retruded position, it can increase stress on the tooth structure or restorations.

Early signs include excessive wear on the most distal teeth, fractures of teeth or restorations, or tooth loss. CBCT can be used as a screening tool alongside a thorough clinical occlusal examination to help identify treatment risks, but it’s crucial to understand that CBCT is not the best imaging method for assessing the position and condition of the disk, and MR imaging is required to evaluate the articular disk’s status.

References

- Yu, W et al. Correlation between TMJ space alteration and disc displacement: A retrospective CBCT and MRI study. Diagnostics 2024, 14,44.

- Jeon, K et al. Analysis of three-dimensional imaging findings and clinical symptoms in patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2021; 11(5):1921–1931.

SPEAR campus

Hands-On Learning in Spear Workshops

With enhanced safety and sterilization measures in place, the Spear Campus is now reopened for hands-on clinical CE workshops. As you consider a trip to Scottsdale, please visit our campus page for more details, including information on instructors, CE curricula and dates that will work for your schedule.

By: Curt Ringhofer

Date: October 7, 2025

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts