Providing an Ethical Second Opinion

People typically enter the dental office for two main reasons. One is that they have a specific, urgent problem that needs prompt attention. Another reason might be that they’re looking to become established as a new patient for routine dental care without really understanding there may be many issues that should be addressed for optimal oral health.

Essentially, they’re asking if the dentist sees any fires that need to be put out before they cause pain and discomfort, and they may or may not be seeking to find a new dentist because they were disgruntled with their previous dentist.

However, a third type of patient presents to the typical dental office occasionally: the ones who schedule to get “a second opinion.”

The challenge with “the second opinion” patient is that there is confusion about what actually constitutes a second opinion from an ethical perspective, especially in this era of competitive revenue-driven dentistry where clinicians are under constant (and often extreme) pressure from corporate and third-party payer influences to sell dentistry regardless of the ethical cost.

Price-shopping patients

In my experience, many patients who request this type of evaluation are price-shoppers looking to see if this dentist will do that crown, filling, etc., for less than the first dentist. It’s important to understand, however, that this is not a second opinion — or at least not an ethical one. This is because fees for services do not necessarily relate to the quality of the diagnosis or the appropriateness of the treatment plan.

Price-shopping patients should raise red flags because they tend to value money more than the doctor/patient relationship, which will always create challenges to providing optimal oral healthcare. The discussion of whether fees are ethical is, quite frankly, outside the scope of a second opinion exam, because making that assessment requires a thorough understanding of all of the variables that go into fee setting — individual overhead, supplies and labs used, etc.

Ethical second opinions are important to the maintenance of standards of care in healthcare professions, and they encourage the autonomy of our patients while protecting the principles of non-maleficence and benevolence, as well as veracity.

Whenever a clinician renders a diagnosis, it should withstand the ethical scrutiny of qualified colleagues. Treatment options rendered for given diagnoses should be in line with those that another reasonable clinician with adequate expertise regarding the diagnosis in question would do. In fact, this is the definition of “standard of care.”

While treatment plans will vary from one clinician to another for a given diagnosis based on the training, skill set, and expertise of a particular clinician, the duty of a clinician rendering a second opinion should be to answer two questions:

- Is the diagnosis reasonable?

- Is the treatment proposed reasonable and appropriate?

In answering the first question, the evidence that was used by the rendering clinician must be carefully and objectively evaluated. For example, were adequate diagnostic tests performed to render the diagnosis according to accepted standards?

Of course, the tests must be reviewed independently to render a second opinion, which means that a diagnostically adequate copy of the test records must be available. (Incidentally, this is also required under HIPAA regulations.)

Case 1: Inadequate records

In the following case, a second opinion was requested by a parent about a substantial treatment plan for his healthy 7-year-old child consisting of sedation and multiple restorations, based on the radiographs in Fig. 1.

Because the radiographs provided were not diagnostic, in my opinion, the first step of the discussion with the parent was to discuss the need for better diagnostic records while maintaining professionalism and not providing unjustified criticism of my colleague. After all, there are always circumstances that make it difficult to obtain optimal results, and I wasn’t present at the time of the examination.

However, answering the first question in the second opinion process quickly allowed me to answer the second question, especially when a clinical evaluation was unremarkable and the behavior of the child during my examination was very cooperative, to the point where I personally would have no concerns about conventional local anesthesia rather than requiring oral sedation. When appropriate evidence for a reasonable diagnosis is lacking, the treatment plan, in my opinion, was not reasonable. I told the parent that I would be reluctant to pursue this treatment plan with this clinician.

Case 2: Clear records, accurate diagnosis

Many times, the patient presenting for a second opinion has been diagnosed appropriately. In this case, a patient presented for a second opinion about a tooth that had been recommended for extraction, but the patient wanted to save the tooth. The provided radiograph (Fig. 2) showed a large post with periapical radiolucency, and there was an appropriate clinical notation that reported the presence of a buccal parulis.

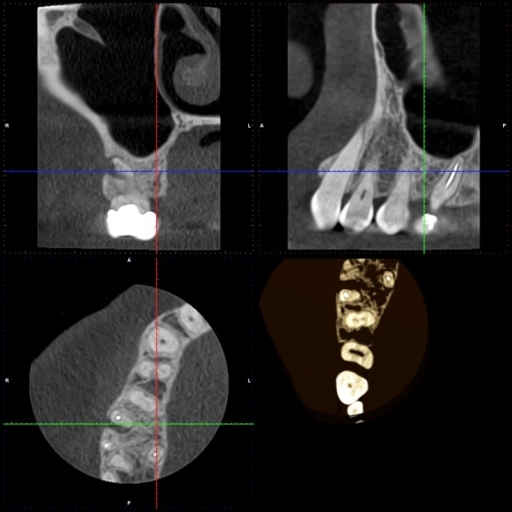

Upon verifying the presence of a parulis with a clinical evaluation, I rendered a second opinion in support of the original diagnosis and treatment plan. When the patient asked if any other option was available, I offered the option to evaluate the tooth with a CBCT. A vertical fracture was discovered (Fig. 3), which further supported the diagnosis. [Editor’s note: See “Supplemental note” below for follow-up discussion.]

There was no discussion in these examples about the cost of treatment, nor was there any solicitation for the patient to be treated by the dentist rendering a second opinion.

Offering additional testing to provide a better augment of the diagnosis did not, in my opinion, constitute an ethical breach because a patient who is legitimately seeking a second opinion is seeking more information to make an informed decision about his/her care. Fees for services are not necessary to provide appropriate information to enhance patient autonomy; the patient usually trusts the dentist offering the second opinion to be honest. The only way for that clinician to be completely objective is to clearly have the mindset that this patient will not become a patient for whom he or she will provide treatment other than a diagnosis, except in an emergency situation. To render a second opinion with any intention of soliciting the patient borders on unprofessional behavior.

It is important that the dentist offering the second opinion remains objective and does not allow his or her preferences to cloud the answer to the second question of the process. For example, if a patient presents with a diagnosis that a tooth has a structural integrity challenge with a large intracoronal restoration with the recommendation for crown therapy, and the dentist rendering the second opinion may not prefer to recommend a crown for that tooth, the question should be, “Is it reasonable to crown the tooth?”

If it is reasonable, the second opinion should support the original diagnosis, but the dentist rendering the second opinion could certainly discuss the benefits and risks of the proposed treatment in an objective manner, along with other reasonable options, without compromising any ethical standard. In fact, this would be a valuable service to the patient and the original dentist that would enhance the patient’s autonomy by giving him or her better information. In fact, this discussion would also uphold the ethical tenet of veracity.

As for follow-up, it would be good practice to encourage the patient to schedule an appointment with the original dentist to discuss any concerns he or she may have about the original diagnosis in light of the second opinion. Occasionally, the patient may want to become a regular patient of the second-opinion dentist. In this situation, if the patient clearly (on his or her own volition) states that desire without solicitation, it might be appropriate to schedule them for a new-patient exam and to develop a new treatment plan, which may or may not be the same as that for which the second opinion was offered.

Second opinions are a wonderful service that ethical clinicians can and should provide for the benefit of the profession and the patients it serves. However, clear parameters and ethical standards should be established by each clinician about what the second opinion entails. It is also wise to develop a policy within each practice about how second opinions should be handled, as well as how to professionally handle those patients who are price-shoppers.

Supplemental note from the author

A hallmark of being an ethical clinician is the ability to admit error. It appears it is appropriate for me to do so regarding my interpretation of the CBCT in the example illustration in this article, and my verbiage may mislead readers into thinking that there is certainty in arriving at a diagnosis based on a CBCT alone. I stated in the article that a CBCT was an option, but I did not clarify what it was an option for. It was not an option for treatment, but rather an option for more diagnostic information. The conventional radiograph alone was adequate, in my opinion, to support the original clinician. However, the patient elected for the CBCT image. It also appears that an elaboration on the discussion surrounding the choices offered to the patient is necessary.

There are multiple factors leading to the diagnosis of a fracture in a case like this that are outside the scope of this particular article, but the possibility of failed endodontic treatment must be considered in the differential diagnosis. One of the options for treatment for this patient was to refer the patient for endodontic re-treatment, direct visualization from visualization of the pulp chamber, and/or root amputation prior to condemning the tooth. In fact, this discussion occurred with the patient along with relative prognosis of restorability, risks, and benefits as well as replacement options with respective risks and benefits. In the original article, it would have likely been better to elaborate on this discussion, and I sincerely apologize for any confusion this may have created.

As has been pointed out in the comments, there is significant concern about reconstructive artifact in visualizing fractures in teeth. In fact, what I interpreted as cracks (which actually were discovered clinically on extraction of the tooth) likely were artifacts. The theorem that was brought up as a challenge in summary states that what can be seen radiographically is actually twice the size of the smallest voxel used, which would mean that the crack would need to be about 0.15 mm wide, which is huge. This highlights a general weakness in the training provided by CBCT manufacturers who may provide “facts” in training that may come from misunderstanding of the image reconstruction process and how those like me who have taken several courses on CBCT interpretation, often provided by manufacturers with a sales focus, may be misled in the actual ability to diagnose detail from CBCT. As another example, we now know that CBCT images in implant planning and measurements are usually accurate to within 0.5 mm, which is far from precision as was originally touted when CBCT imaging was first introduced. I am thankful to Dr. Jeff Pafford for offering clarity about this, especially as it applies to endodontics.

Hopefully this error in interpretation of the CBCT image in this case has not significantly distracted from the point of my article. Offering ethical second opinions should simply answer two questions: Is the original diagnosis appropriate, and is the proposed treatment reasonable? I highlighted the point that it might be appropriate to acquire more diagnostic data if necessary, which remains true.

There is definitely a need for well-developed CE courses covering the gamut of CBCT use that is not focused on selling software, units, etc. This case is just one of those examples. A great deal of important information can be gained from the use of CBCT technology, but there needs to be greater understanding of its limitations.

SPEAR STUDY CLUB

Join a Club and Unite with

Like-Minded Peers

In virtual meetings or in-person, Study Club encourages collaboration on exclusive, real-world cases supported by curriculum from the industry leader in dental CE. Find the club closest to you today!

By: Kevin Huff

Date: February 14, 2018

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts