Bonding to Enamel and Dentin: A Dichotomy of Substrates

Editor’s note: Adhesion to tooth structure (dentin and enamel) is a routine procedure in general dental practice in which the grail is predictability and longevity. In this series of articles for Spear Digest, Resident Faculty member Dr. Jason Smithson will cover the past, present, and future of bonding systems and adhesive strategy.

- Part 1: The challenges of bonding to enamel and dentin, and the history of enamel bonding.

- Part 2: Current strategies for bonding to enamel: substrate preparation.

- Part 3 (Dec. 16): Current bonding strategy recommendations.

The challenge in bonding is adhesion to two structures that are entirely different: enamel and dentin.

- Enamel is largely inorganic apatite: 75% hydroxyapatite,19% carbonate apatite, 4.4% chlorapatite, 0.66% fluorapatite and 2% non-apatite forms. Less than 1% is organic, and there is very little water.1

- Dentin is a completely different deal: It consists of hydroxyapatite crystals (45%) embedded in a collagen based extra-cellular matrix (33%) and has a much higher water content (22%).

Because dentin is essentially a wet organic structure with reduced inorganic content, bond strengths and longevity are reduced in comparison to enamel. The result is that different bond strengths are achieved when simultaneously bonding to enamel and dentin.

Surface energy and bond strengths

The reason for the disparity in bond strengths is related to surface energy — a measure of how attracted a material’s molecules are to each other or other materials’ molecules.

Materials with low surface energy are more difficult to bond to, while those with high surface energy are easier. Higher surface energy is seen in substrates with higher inorganic components, such as enamel.

Etching enamel creates etch patterns, which increases the surface area and results in an increased surface energy. (Etching also removes the tooth’s pellicle, which results in an even higher surface energy — one of the reasons it’s smart to perform particle abrasion before any enamel-bonding procedure.)

Bonding to dentin is more challenging because collagen and composite resin both have low surface energy.

Wettability and surface tension

High wettability — the ability of a liquid to spread out or flow when applied to a solid, rather than form beads — is also required for high bond strengths.

High wettability is the result of high surface energy of the material being bonded and low surface tension of the bonding agent. A liquid with high surface tension tends to form droplets because cohesive forces pull the molecules toward the center of the liquid, minimizing surface area, while a liquid with lower surface tension tends to spread over a surface. If a bonding agent had high surface tension, it would tend to form droplets on the surface of the substrate and wouldn’t spread while wet.

In summary, the goal in bonding is to create the highest surface energy on the enamel and dentin and use a bonding agent with low surface tension. The result will be high wettability and high bond strengths.

“The goal in bonding is to create the highest surface energy on the enamel and dentin and use a bonding agent with low surface tension. The result will be high wettability and high bond strengths.“

Enamel bonding: A historical perspective

Buonocore became the father of adhesive dentistry in 1955 when he found that acrylic resin could be bonded to human enamel after the enamel was conditioned (etched) with phosphoric acid.

Buonocore, who based his research on the observation that phosphoric acid was used to improve the adhesion of acrylics and paints to metal surfaces in industry, named the process “bonding” and theorized potential applications such as pit and fissure sealants and Class III and V restorations.2

Later work by Gwinnett and Matsui3 showed that acid etching removed around 10 microns of the enamel surface in addition to creating a “porous layer” 5–50 microns deep. When a low-viscosity bonding resin was applied to this layer and polymerized, it flowed into the porosities to create “resin tags,” creating a bond between enamel and resin. It was also noted that etching enamel increases its surface area and wettability.

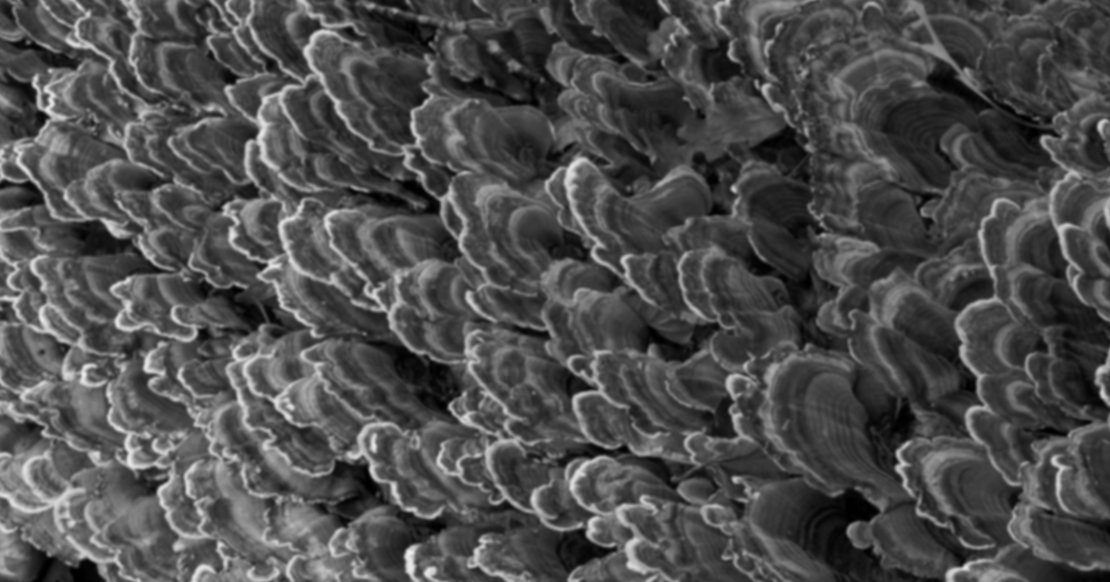

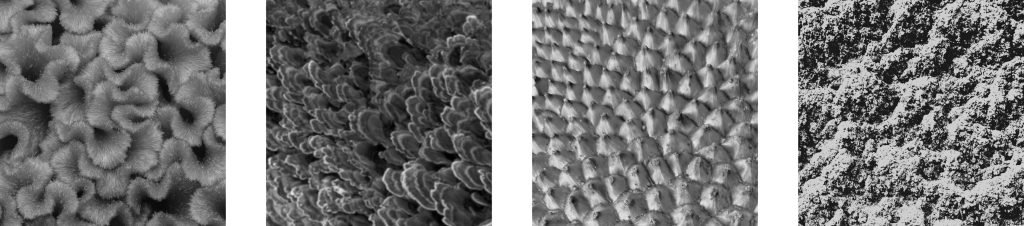

Further work by Gwinnett4 and later by Silverstone5 noted the classical three distinct patterns of enamel etch:

- In Type 1, the most common, the enamel prism cores were removed preferentially, leaving the prism peripheries intact. The gives a honeycomb-like structure.

- Type 2 is the opposite of Type 1: The peripheries are removed, leaving the cores intact. This results in a cobblestone-type appearance.

- Type 3 has a less distinct pattern that includes areas of both Type 1 and Type 2 etch patterns, in addition to patterns that seem unrelated to prism morphology.

A further study by Galil and Wright6 noted that Type 1 and 2 patterns were predominantly seen on the coronal aspects of the buccal surfaces, whereas Type 3 patterns were in the middle third.

Galil and Wright also recorded two more etch patterns, noted on the cervical surfaces:

- Type 4 has pitted surfaces with structures that resemble unfinished maps.

- Type 5 has smooth, flat surfaces.

Initially, there was some debate as to phosphoric acid concentrations and etch times.

Lower concentrations had the tendency to produce precipitates of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate, which was not easily removed and reduced bond strengths. Conversely, higher concentrations dissolved less calcium and reduced etch depths.

Silverstone noted that acid concentrations between 30% and 40% provided the most retentive etch patterns. Further, the degree of calcium dissolution and etch depth increased up to a concentration of 40%. Consequently, most commercially available dental phosphoric acid etchants are 30–40% (predominantly 37%).

In terms of etch time, the traditional default has always been 60 seconds. However, Barkmeier’s studies with SEM showed that etch patterns were broadly similar with 15-second etch times and that shear bond strengths were unaffected.7

In Part II of this series, we’ll discuss current strategies for bonding to enamel.

References

- Kunin, A. A., Evdokimova, A. Y., & Moiseeva, N. S. (2015). Age-related differences of tooth enamel morphochemistry in health and dental caries. EPMA Journal, 6(1), 3.

- Buonocore, M. G. (1955). A simple method of increasing the adhesion of acrylic filling materials to enamel surfaces. Journal of Dental Research, 34(6), 849-853.

- Gwinnett, A. J., & Matsui, A. (1967). A study of enamel adhesives: the physical relationship between enamel and adhesive. Archives of Oral Biology, 12(12), 1615-IN46.

- Gwinnett, A. J. (1971). Histologic changes in human enamel following treatment with acidic adhesive conditioning agents. Archives of Oral Biology, 16(7), 731-IN15.

- Silverstone, L. M., Saxton, C. A., Dogon, I. L., & Fejerskov, O. (1975). Variation in the pattern of acid etching of human dental enamel examined by scanning electron microscopy. Caries Research, 9(5), 373-387.

- Galil, K. A., & Wright, G. Z. (1979). Acid etching patterns on buccal surfaces of permanent teeth. Pediatric Dentistry, 1(4), 230-4.

- Barkmeier, W. W. (1986). Effects of 15 vs 60 second enamel acid conditioning on adhesion and morphology. Operative Dentistry, 11, 111-116.

SPEAR ONLINE

Team Training to Empower Every Role

Spear Online encourages team alignment with role-specific CE video lessons and other resources that enable office managers, assistants and everyone in your practice to understand how they contribute to better patient care.

By: Jason Smithson

Date: November 18, 2025

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts