Frank Phrases: Give Patients the Option to Do Nothing

I am generally outgoing and can start a conversation with just about anyone. Some have even described me as “overwhelmingly extroverted.” So, early in my career, I was under a lot of pressure to go into sales.

I heard from successful salespeople repeatedly that I was a natural and that I would be great. So, in 2005, I co-founded an in-home personal training business and started selling (along with everything else you do to run a business) full-time.

As it turns out, I am not very good at selling. In those first few years, I had to work extremely hard to be good. Part of becoming a student of selling is going deep into sales systems, theories, and social science research. The goal was to understand how people make decisions and what influences those decisions.

After this trial by fire, I spent time in graduate school going deeper into primary research, ultimately building a research-driven selling model as part of my program. This is a long-winded way of saying that for more than a decade, I have been fascinated by the process by which people are persuaded to make decisions and the things individuals can do to influence this process.

When I came to Spear, I immediately latched onto the principles Dr. Frank Spear taught about patient communication and case acceptance. What fascinated me was that the more I dove into the process he created, the more I realized how perfect it was.

Dr. Spear is one of the most intuitive, persuasive communicators ever. When I look at social science literature, he has built an effective system for helping and teaching patients to see the value of dentistry.

While some of this is detailed in our book, Case Acceptance in the Modern Dental Practice, my “Frank Phrases” articles aim to go deeper into several subtle details and explain the science behind why this works. The goal is that excellent clinicians will be better able to communicate in a way that helps patients see the value of the care they provide.

Elements of a Co-Discovery Conversation

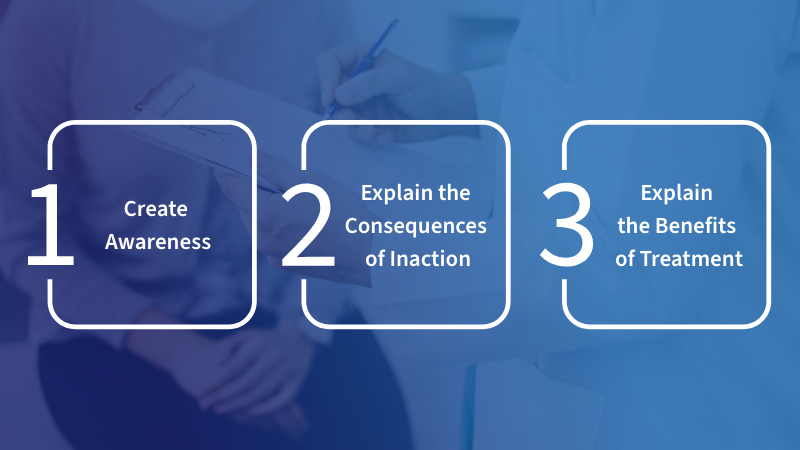

This article starts with one of the key components of the co-discovery system Dr. Spear has been teaching for 30+ years. We have numerous videos on Spear Online that go into this in detail, but the essence of a co-discovery conversation can be boiled down to:

- Create awareness: Preferably using a visual aid to help the patient become aware of conditions in their mouth.

- Explain the consequences of inaction: Doing nothing is always an option to help them understand what can happen and give them a sense of the potential timing for these consequences.

- Explain the benefits of treatment: Not the treatment plan but how the treatment will help the problem.

How the Consequences of Inaction Change the Patient Conversation

Let’s explore the idea of explaining the consequences of inaction. The first brilliant aspect is that simply acknowledging that doing nothing is an option immediately changes the power dynamic of the conversation. It moves from a zero-sum game to one where the patient is invested in their treatment.

What is interesting about this is that it helps to immediately counter any previous negative interactions the patient may have had. We know that past attempts at persuasion change how people perceive all future persuasion attempts. Friestad and Wright’s persuasion knowledge model pulls together behavior research to help us better understand how previous attempts to persuade can affect future interpretations.

Essentially, any time we experience a sales or marketing message we build mental models based on past experiences to help us make better decisions in the future. By putting the power back in the patient’s hands, you help to disarm them and remove any skepticism that may exist due to previous clinicians’ more authoritative presentations.

Dr. Spear is one of the most intuitive, persuasive communicators I have ever come across, and when I look across social science literature, he has built an effective system for helping and teaching patients to see the value of dentistry.

The next key in this step is that you are helping them to clearly understand what can happen if they choose to do nothing. As humans, we are wired to place a higher value on avoiding risk over potential rewards. This makes sense if we look at human history; our ancestors who were good at avoiding risks more often ended up surviving and creating the next generation. This was demonstrated by behavior economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

In their work on Prospect Theory, they discovered a cognitive bias called the framing effect. Essentially, when presented with options, people are more likely to choose options that are framed in a way that emphasizes avoidance of a consequence than those framed in a way that emphasizes a reward.

For example, in one study 93% of doctorate students registered for classes early when a penalty fee for late registration was emphasized, but only 67% did so when the same number was presented as a discount for early registration.

This is not to say that as a clinician you need to paint an apocalyptic picture of the condition. Your description should be real, and you should give them a realistic sense of timing. For example, when talking to a patient who has recurrent decay around a large filling you might try something like:

- “The mouth is a hostile environment and over time the same forces that caused you to need a filling in the first place are beginning to affect this restoration.”

- “The challenge now is that more of the tooth is compromised, which can lead to a more catastrophic failure, including the tooth cracking below the gumline, which would require extraction.”

- “It is hard to say exactly when this will happen but when you bite down there can be up to 220 lbs. of pressure per square inch. So, one popcorn kernel could mean the end of it, but it also might be fine for another six months to a year.”

In this statement, the patient is given some objective, easy-to-understand facts, which allow them to make an informed decision. This helps to bring them into the decision-making process, arming them with the information you already have.

It clearly explains a realistic potential consequence of doing nothing (crack and extraction) and a sense of timing of when this could happen.

References

- Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1-31.

- Plous, S. (1993). The psychology of judgment and decision making. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

SPEAR ONLINE

Team Training to Empower Every Role

Spear Online encourages team alignment with role-specific CE video lessons and other resources that enable office managers, assistants and everyone in your practice to understand how they contribute to better patient care.

By: Adam McWethy

Date: May 3, 2021

Featured Digest articles

Insights and advice from Spear Faculty and industry experts