Most restorative dentists have encountered this challenging clinical scenario: A patient presents with a terminal molar (often a second molar) that requires a crown or an onlay and although treatment seems straightforward, after appropriate depth cuts and tooth preparation, the molar contacts the opposing one, resulting in a lack of restorative space.

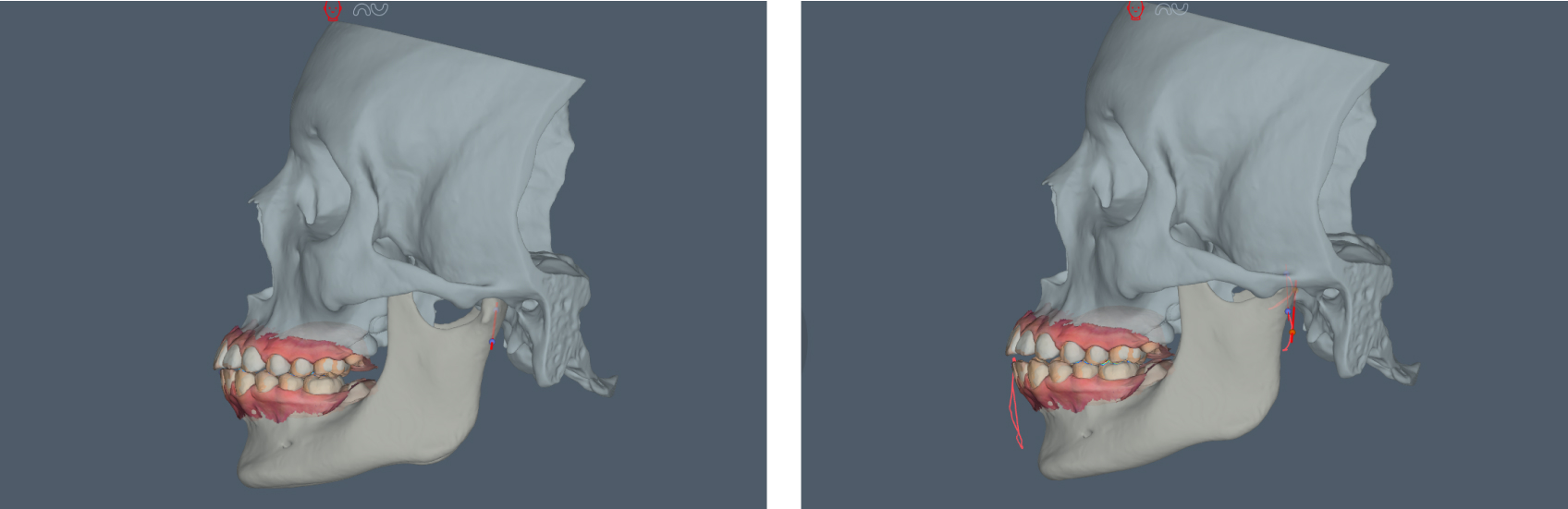

The “last tooth in the arch” dilemma occurs when treating the terminal tooth inadvertently destabilizes the patient’s habitual occlusion. What initially presented as a localized tooth-based restorative need now reveals a deeper, joint-based occlusal discrepancy: the slide from a fully seated condylar position to maximum intercuspation. Once the habitual (MIP) occlusal contact (Figure 1) is altered and the condyle fully seats into centric relation (Figure 2), the true occlusal relationship is expressed, showing the lack of interocclusal space.

Why This Occurs: The FSCP–MIP Slide

Most patients function in a habitual MIP position and may not be in a fully seated condylar position. According to Posselt, CR–MIP discrepancies are present in up to 88% of patients, meaning most patients aren’t functioning in centric relation.1 The terminal molar is often the initial and only tooth in contact, and muscles accommodate the mandible in a forward position to achieve more occlusal contacts without patients even being aware.

When the FSCP contact is removed during treatment, the condyle can fully seat into a retruded position, resulting in a Class II mandibular shift. In this retruded joint position, the restorative space disappears, leaving the clinician in an unwanted and unexpected dilemma. This may be even more critical when treatment-planning an implant crown in the terminal molar position; because implants lack a periodontal ligament, screw-loosening implant failures can arise if the restoration is in hyperocclusion.

Recognizing the Problem Before Treatment Starts

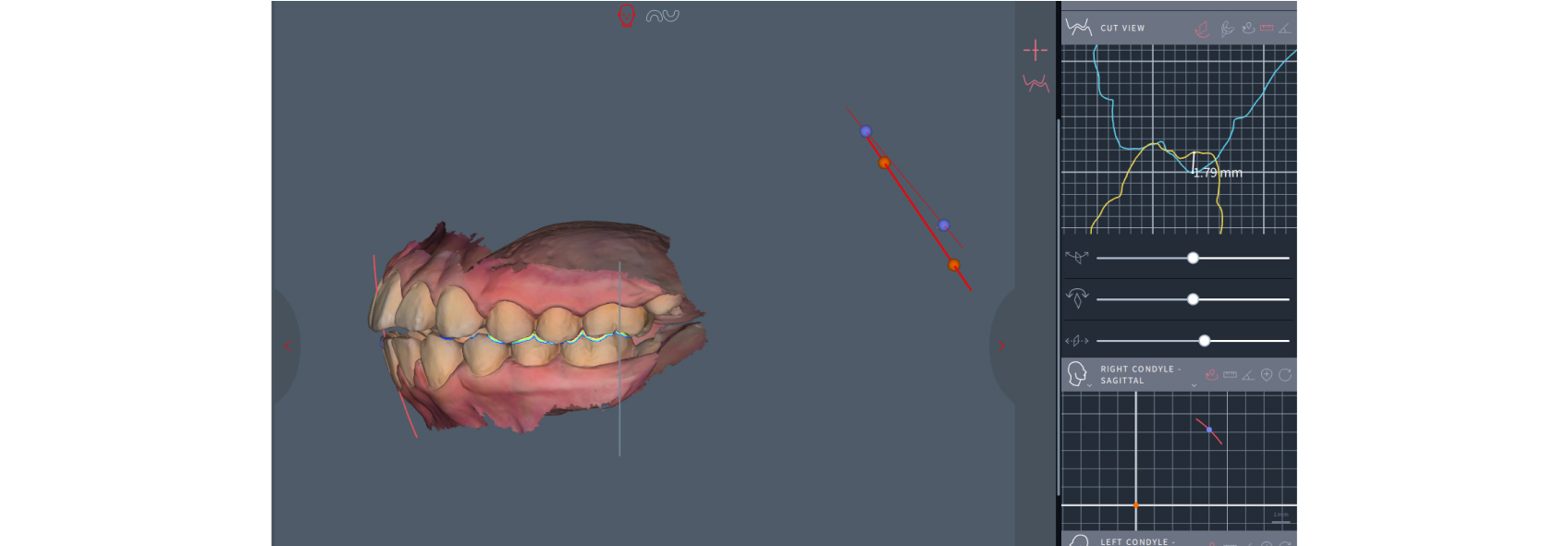

Identifying the FSCP–MIP slide is essential before any irreversible treatment begins. A deprogrammer such as a Lucia jig, a leaf gauge (Figure 3), or a Kois deprogrammer can position the mandible into a FSCP. Measuring the horizontal and vertical bite shifts between FSCP and MIP (Figure 4) will indicate the direction and degree of the slide.

A slide greater than 2 mm — typically the thickness of the articular disc — should raise a red flag because it suggests there may be an anteriorly displaced disc, resulting in a loss of vertical dimension at the joint level that will reduce the interocclusal space.

Clinical red flags for patients with potential slides:

- Molar-only tooth attrition

- Posterior interferences

- A history of failed restorations on the terminal tooth

- A history of joint noises

- A history of TMJ pain

- Jaw muscle tension

- Pain or tension on loading

- Limited range of motion

- Difficult to deprogram

- Class II bite — bicuspids extracted, deep bite, retroclined maxillary incisors, overerupted lower incisors, lack of anterior coupling

Clinical Management When Slide Is > 2 mm

When the FSCP–MIP slide is greater than 2 mm, treatment moves from a single-tooth-based solution to more comprehensive occlusal management. As my fellow Spear Resident Faculty member Dr. Jim McKee often puts it: “Are we playing checkers, or are we playing chess?" Meaning: “By evaluating the occlusion — both at the back end of the system as well as the front of the system — it becomes evident that many of the tooth-based malocclusions that have confused our profession can be explained by the changes in the temporomandibular joint level.”2

The goal of treatment is to create bilaterally stable posterior contacts. Start by deprogramming patients and obtain mounted models in FSCP to begin a diagnostic evaluation to explore possible management options, which may include:

- Occlusal equilibration — adjusting the opposing dentition

- Root canal therapy with crown lengthening

- Opening the vertical dimension

- Orthodontic molar intrusion, surgical impaction

|

Hands-On Occlusion Learning With This Author! Dr. Julie Kwon and fellow Resident Faculty members Dr. Darin Dichter and Dr. Curt Ringhofer lead the three-day workshop Occlusion in Clinical Practice, which explains how to assess function and plan treatment for restorative patients. To see more information and all upcoming dates for this workshop, which earns 22.75 CE credits, click below. |

Special Considerations With TM Joint Stability

This scenario often reflects loss of vertical dimension at the TM joint, where the articular disc is no longer in position to protect the condylar surface. TM joint stability must be assessed to ensure occlusal stability before initiating complex treatment such as full-arch restoration, orthodontics, crown lengthening, or orthognathic surgery because if the joint space or position changes during treatment, so will the occlusion. Furthermore, delay definitive treatment in patients with active joint pain, locking, or muscle symptoms until symptoms are managed, often with splint therapy or provisional restorations.

Joint imaging (MRI/CBCT) may be indicated to determine joint diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic options. The principles of identification of high-risk patients is taught in the Occlusion in Clinical Practice workshop, while a deeper dive into joint diagnosis and management is taught in the Advanced Occlusion workshop.

Practice Management Tip

Crowns or onlays on terminal molars often are recommended during the hygiene appointment, so being able to recognize the high-risk condition before scheduling is helpful. I recommend having a leaf gauge in the hygiene room available for these instances. This way the patient can deprogrammed to a fully seated condylar position and measure the slide to MIP.

- If the slide is > 2 mm, invite the patient to return for diagnostic records before proceeding with treatment.

- If the slide is < 2 mm, then determine the next point of contact. If another contact is close, then perhaps it will hold the new MIP.

Conclusion

The “last tooth in the arch” dilemma is a classic example of how treating a tooth without understanding the occlusal risk can lead to unintended consequences.

Recognizing FSCP–MIP slides before initiating treatment on terminal teeth helps avoid the dreaded scenario: prepping a tooth and realizing there’s no space to restore it — after the fact. Knowing the risks in advance and educating patients about their joint-based occlusal instability puts clinicians in control and leads to more stable, predictable outcomes.

References

- Posselt U. Studies in the Mobility of the Human Mandible. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 1952, 10–19.

- McKee JR (2017). Redefining occlusion. Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular Practice, 35(6), 343–344.