Fixed Partial Dentures vs. Implants Part I - Is One Better Than the Other?

By Frank Spear on January 27, 2019 | commentsAs someone who has limited my practice to esthetics and fixed prosthodontics, the arrival of osseointegrated implants, predictable adhesion and strong, bondable tooth-colored materials changed treatment planning (and treatment) more than anything else for me - especially since all my dental school and graduate perio-pros education occurred prior to osseointegrated implants or predictable adhesives existing in the U.S.

But all my years in dentistry before those wonderful options existed taught me that traditional approaches to treatment, such as a three- or four-unit fixed partial dentures, could also be extremely successful.

In many ways, my reason for writing this series of articles has been motivated by several recent Spear TALK posts showing patients with existing FPDs that need to be replaced (often due to caries) and the debates that arose about how to proceed, almost always acknowledging that implants were the most appropriate future treatment (which, in most cases, they are).

But the other side of that is a sense I get that for many of today’s clinicians, a traditional FPD is substandard care that may fail in a week or surely could not do as well as the implants long-term. And yet, for many patients, implant restorations are simply not economically feasible, while an FPD may be. Of course, many implant advocates will say that the FPD will be money down the drain in a few years, and then the patient will still have to ultimately get the implants.

So over the course of several articles, I hope to see if I can clarify the reality of the survival and success rates of FPDs vs. Implants, including patient factors that may influence the long-term survival or success of both types of restorations.

To do so, I am going to follow a wonderful quote from former New York Senator Patrick Moynihan who said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.”

For me, that means using long-term studies, preferably systematic reviews, that compare the treatment modalities at 10 (and, when possible, 20) years, along with the complication rates of each - though you would be amazed at how few articles look at either modality past 10 years.

I’ll end this first article with two simple cases. Patient 1 is a female in her early forties with an existing three-unit anterior FPD that is not esthetically pleasing. She also has a very high smile line. Patient 1 has a great ridge for a single-tooth implant, which would have allowed her to have three single-unit restorations. She also has central and lateral abutments that are very healthy, and both are vital. She chose to have a new three-unit FPD. I was very comfortable with her choice.

Patient 2 is also a female in her early forties with a vertically-fractured right central incisor, and also an extremely high smile line. Other than the right central, none of this patient's incisors are restored. I presented both an FPD and single tooth implant as options, but strongly suggested that the implant was a much better choice in order to avoid touching the adjacent central and lateral. She agreed.

Having seen both cases, the question is: what does the literature tell us about how they will do over time, and what kind of complications may arise? I’ll start with a 2007 paper from Berne, Switzerland that compared all the possible prosthetic options over 10 years: tooth-supported FPD, tooth-supported cantilever FPD, implant-supported FPD, tooth- and implant-supported FPD, and finally, implant-supported single crowns.

The results of the five-year study found all the different options statistically identical in their success rates: 91 to 95 percent, seen in green text on the slide. At 10 years, the tooth-supported cantilever FPDs and the tooth- implant- supported FPDs had decreased significantly, seen in the red text on the slide. However, the tooth-supported FPDs, implant-supported FPDs, and implant-supported single crowns were all statistically identical: 86 to 89 percent. In fact, the tooth-supported FPDs and implant-supported single crowns only varied by 0.2 percent.

So what does this allow us to say to patients 1 and 2? For the next 10 years, their success rates should be nearly identical. Of course, both had ideal presentations for the treatment chosen: vital abutments, anterior three-unit FPD, single-tooth implant with a healthy patient and good bone. What the study doesn’t tell us is what to expect at 20 years, but a future article will have that data.

There is one final area that we haven’t discussed about patients 1 & 2: what is the likelihood that they will experience complications over the 10 years that require some maintenance? It is important in looking at the results to realize this article was published in 2007, so many of the implants were placed during the 1990s to get their 10-year follow-up by 2007. The significance of this is that many of the implants were probably a more traditional external hex design, which does have a risk of screw loosening if placed under heavy load.

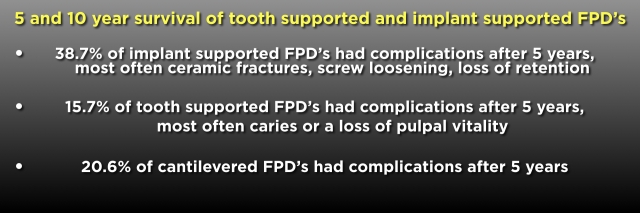

Bottom line, as you can see from the slide below, is that the implants had a much higher incidence of maintenance issues over 10 years than the FPDs.

To conclude part 1 of this series, I hope you get an idea of the flavor the series will take. I am certainly pro-implant, but I do feel a need to represent the facts about FPDs from research, not simply people’s opinions.

(If you enjoyed this article, click here for more by Dr. Frank Spear.)